In Focus: Equal Pay. It’s Complicated.

The fight for equal pay isn’t having the effect on closing the gap that it used to.

When Joan Hermsen surveys the national landscape in the gender wage gap, she sees some encouraging signs. But when the MU associate professor of sociology digs a little deeper into the trends, the picture becomes more complicated.

“It’s closing more slowly than it has in the past,” Hermsen says. “There’s a broader concern about these measures that we typically use to demonstrate growing gender equality in our society, that the process of change on those has slowed down. Generally, there is still improvement, it’s just that it’s much slower than it was two decades ago.”

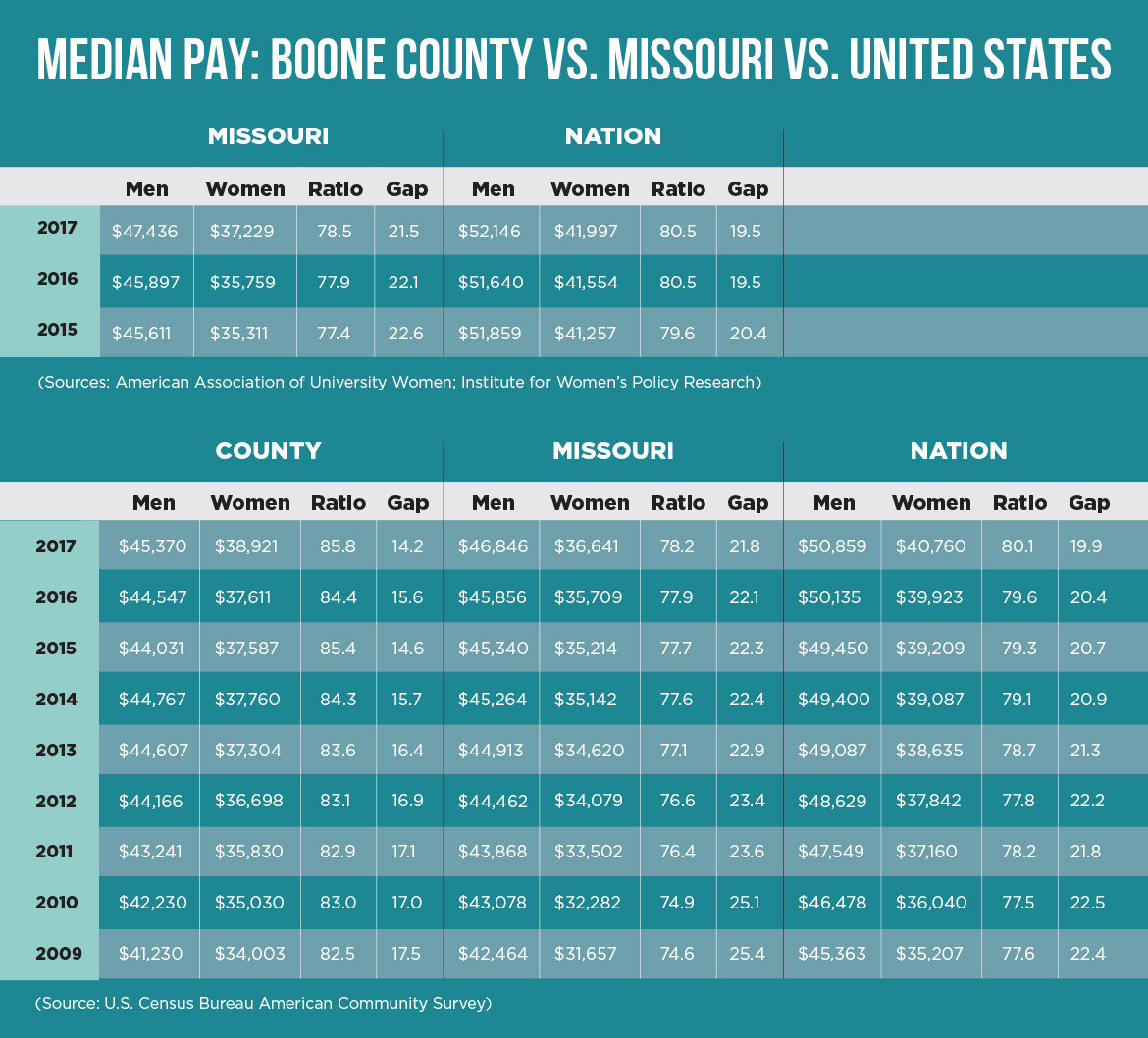

According to data from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, the median annual earnings for full-time, year-round female workers were 80.5 percent of those for men in 2016, a pay gap of 19.5 percent. That number has budged only 6.8 percentage points from 2000. The gap closed a full 10 points over the same time span from 1984 to 2000, from 36.3 percent to 26.3 percent.

And where you live has a huge bearing on how likely women are to be paid a more equal wage.

“You can kind of think about some places where the gender wage gap might be equal to what the national wage gap would’ve been in 1970, or women’s labor force participation rates might resemble what it would’ve been like in 1960,” Hermsen says. “That’s always a piece of the story that gets lost — there is a lot of variation. If we think that women in work or pay equity are important factors in women’s broader autonomy, we can begin to think about how different parts of our own state might be very different cultural experiences for women living there based on their more limited access to better-paid jobs.”

Missouri ranked 30th in the nation with a wage gap of 21.5 percent in 2017, according to research from the American Association of University Women. The state’s situation is much better than, say, Louisiana (31.2 percent) but much worse than California (10.9 percent).

Within the state, according to Women’s Foundation research gleaned from U.S. Census Bureau data from 2012 to 2016, Boone County ranked 15th among Missouri counties with a 15.6 percent wage gap in median pay. Among the state’s 10 most populous counties, only Greene County (around Springfield, 18.4 percent) and Jackson County (suburban Kansas City, 18.1 percent) came close to matching Boone’s equity. And the county’s gap has closed slightly more than 3 percentage points in the past eight years.

Contributing Factors

Aside from geography, factors such as profession and race play into how likely a woman is to be compensated the same as a man of her similar standing and work experience.

“For professions with smaller gaps, you could think about industries that are more regulated on this, ones where there’s collective bargaining,” Hermsen says. “Education, with public school unions, government sector work — they generally have smaller pay gaps. In particular kinds of manufacturing, with a heavy presence of unionized plants, you’d see it more.”

According to national IWPR data from 2017, female secondary teachers made about 89 percent of the median wages of males — a wage gap of 11 percent — while the gap in financial managers was nearly 29 percent.

Race also plays a significant role. While African American women made 92.5 percent of the earnings of black men in 2017, according to IWPR research, they made only 67.7 percent of white men.

Boone County’s relatively high rate of college-educated workers leads to higher wages across the board, although Hermsen says men who earn degrees have seen their wages rise disproportionately higher than women with degrees over the past two decades. The only group that seems to be immune from that trend, Hermsen says, is Asian American women, who are generally a highly educated workforce that disproportionately secures high-paying jobs in STEM fields.

Legal Remedies

The only statewide law on the books in Missouri governing equal pay was enacted in 1963. The AAUW rates Missouri as one of 17 states with “weak” equal pay protections because of the provisions the law lacks.

Todd Werts, of the Columbia-based Lear Werts law firm, agrees with that assessment of the Missouri law. With the way it’s written, the burden on any plaintiff who wishes to bring suit under the state law is to prove that gender was the only factor in the pay difference. And, if found in violation, the punishment for the employer isn’t exactly dire.

“The remedy it provides is whatever pay the woman was shorted,” Werts says. “Most wage and hour laws you see have that plus some additional amount to cover the hardship. That provides an incentive for the employer to actually provide for both the letter and spirit of the law. There’s not really a disincentive, as currently written. ”

Former Governor Jay Nixon signed an executive order in 2015 aimed at eliminating the wage gap in the Missouri executive branch and strongly encouraged private employers to “identify and address any gender wage gap in order to ensure that all Missourians receive equal pay for equal work.” But attempts to pass equal pay reform on a statewide level have stalled amid calls to address root causes instead of mandating compliance.

“You don’t hear very much about big legislative actions around pay equity anymore,” Hermsen says. “When you hear that interest in moving legislation, it’s more about how we make it possible for women to both work and care for their kids: having parental leave policies, paid if possible, available to workers, so that they can easily return back to their jobs. There have been efforts at the state level to figure out ways to put programs in place in elementary through high school that would encourage young women to keep thinking about careers in science and technology. It’s those kinds of steps that are being taken more so than legislating pay equity.”

Werts says there are other tools in workers’ arsenals if they’re looking to prove gender wage discrimination. The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, signed by President Barack Obama in 2009, expanded the timeframe during which plaintiffs can file equal-pay lawsuits. Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 lists gender among its classes protected from workplace discrimination, as does the Missouri Human Rights Act, though Werts says recent amendments to the state act have lessened its protections.

Such cases are not easy to prove.

“At a macroeconomic level, it really is obvious that, on the whole, women continue to make less for similar work than men,” Werts says. “When you get into a microeconomic analysis of trying to prove specific examples, it’s harder.”