Tube to the Future

Imagine it’s 1903 and a couple of brothers who sell and repair bicycles for a living keep pestering you to invest in their idea to develop a machine that would allow people to move from place to place without touching the ground. You’re convinced the only thing in their sky will be pie, not people. The next two decades will prove you wrong.

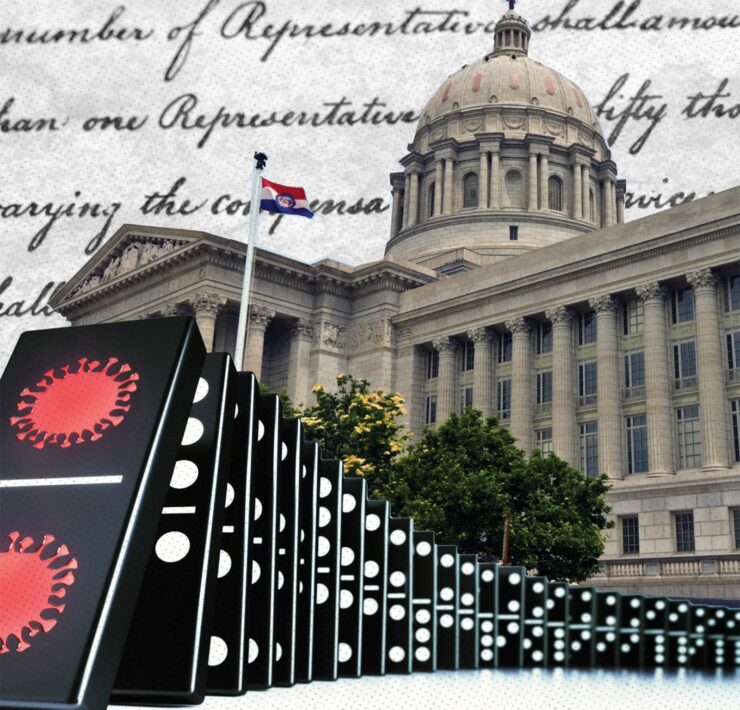

Now, it’s 2019 and people are talking about a California car builder putting a pod inside a vacuum tube that, using magnetic levitation, could blast occupants the 250 miles from Kansas City to St. Louis in about half an hour. Are you in?

A growing number of state officials clearly are.

Missouri House Speaker Elijah Haahr has put together a task force to study the potential for “vactrain” transportation — more commonly called Hyperloop — and how the state should be involved. This will include analysis of whether public dollars should be used to lure a vactrain project to the Missouri River Valley, presumably from the developers of Virgin Hyperloop One. That’s the effort begun in 2012 by Elon Musk, with the more recent financial support of British billionaire Richard Branson (hence, the name “Virgin Hyperloop One,” as in Branson’s Virgin Records and Virgin Atlantic Airways).

Hyperloop (a name trademarked by Musk two years ago) engineers have been testing the technology in the deserts of California and Nevada, and Haahr told state capitol reporters he’s been a witness to those tests. “This is something I’ve been very excited about for a long time,” he said at a March news conference.

The pod reaches its impressive speeds in two ways: first, it uses magnetic forces to propel forward without touching anything and, therefore, without friction or drag; second, traveling inside a vacuum tube to eliminate wind resistance. While they’re not there yet, developers say land-based pods moving at jet aircraft speeds are possible. Last fall, the Kansas City-based Black and Veach engineering firm conducted a feasibility study of a Hyperloop system between Kansas City and St. Louis and concluded the system was buildable at a cost between $7.5 billion and $10 billion. “Obviously, the work Black and Veach did early on was very helpful in getting us to where we’re at now,” Haahr noted.

Haahr has tabbed Missouri Lieutenant Governor Mike Kehoe to chair the task force. “We’re a state that has the ingenuity, the technology, the resources to look at what’s next in the future, and I think this is an exciting step,” Kehoe told reporters at the news conference. “You know, we’re the state that funded the first transatlantic flight with Lindbergh. We’re the state that built the Eads Bridge over the (Mississippi) river when nobody said it could be done. We’re the state that produced the (McDonnell Douglas) engineers that helped to put man on the moon.” Columbia State Senator Caleb Rowden, Callaway County Representative Travis Fitzwater, and UM System President Mun Choi are among the task force members.

The group will have private-sector input from people such as Andrew Smith of the St. Louis Regional Chamber of Commerce and the Missouri Hyperloop Coalition, which secured the private funding for the Black and Veach study. “Effectively, what this would do is unify the state and create a single economic development mega-region,” Smith told reporters. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported it was the regional chamber’s Austin Walker who solicited the interest of Governor Mike Parson and who approached Haahr about forming the task force. During the capitol news conference, Smith described the Hyperloop project as a chance for the state to position itself as a “global tech leader.”

A nonprofit called Heartland Hyperloop Inc. emerged last fall and launched an online petition to urge Governor Parson to include the Hyperloop in the state’s transportation investment plan. Spearheaded by former Missouri House Speaker Steve Tilley, Heartland Hyperloop has advocated for a combination of public and private funding for the vactrain. Clearly, that multi-billion-dollar price tag is the elephant in the pod . . . er, room.

As a former member of the Missouri Highways and Transportation Commission and a former state senator who has backed unsuccessful efforts to increase taxes for highway construction, Kehoe insisted he would not support any use of state money for the Hyperloop until the state has agreed on a plan to pay for roads and bridges. Voters in November rejected a fuel tax increase and previously said no to a general sales tax to fund transportation infrastructure projects. Haahr added that “before we would spend any public money, we would want to have concrete plans to go forward.”

Kehoe indicated that the task force will spend the next several months holding public meetings in St. Louis, Kansas City, and Jefferson City. He said the group wants to have a final report ready for Haahr by September. As it works to develop and test the vactrain technology, the Hyperloop organization has presented the project as a competition, with states vying to be first. Those in the game see an unprecedented economic potential in being on the cutting edge. “When you look at St. Louis and Kansas City combined, you’re talking about an area that really has the same kind of potential as a Boston or a Bay Area or a Seattle,” Smith said.

Kermit is an award-winning 45-year veteran journalist and one of the longest serving members of the Missouri Statehouse press corps.