Opinion: Community Policing Comes at a Price

There is an old joke in law enforcement that is, sadly, true. It goes, “There are two things cops hate: The way things are and change.”

Policing in Missouri came under an international microscope after the shooting of an unarmed man in Ferguson, Mo. The incident itself was investigated and found to be reasonable by local, state, federal, and Department of Justice investigators. However, the aftermath of that incident and several other police shootings around the country resulted in much professional soul searching, reflection, and review of police and policing in general. Most of these reports and reviews recommended change towards a community-oriented policing philosophy.

Community policing is the preeminent reform goal in modern policing. It differs from traditional policing in a shift towards more citizen involvement, a different geographic focus, more opportunities for interactions with citizens, and an emphasis on crime prevention.

Nationally, we have experienced a 25-year long reduction in crime. The use of data-driven techniques and intelligence-led policing has been successful in maximizing resources and addressing the causes of crime. At the same time, the expectations on police have expanded. A police officer is now expected to be the default crisis call for everything from a lost child to a car misplaced in a drunken haze to a pizza being delivered without being cut into slices (a real 911 call for a Columbia police officer). This results in more demand for service despite the downward trend of actual crime.

Patrol officers working a shift typically respond to 15 to 20 calls for service in their 10-hour shift, yet only four or five of those are criminal matters resulting in a criminal police report. Officers spend a large amount of time dealing with non-criminal incidents, civil disputes, and medical (both mental and medicinal) incidents. Even though officers’ training and the department’s organizational structure is based on the four or five criminal incidents, the public — perhaps rightly — demand that officers be experts at the other eight to 10 non-criminal situations they are the default solution to.

Almost every citizen has instant access to 911 dispatch now. The consequence of every person having 911 available in their hands and cars at every second has been that we receive hundreds of calls for service for an incident we would have received only a few calls for prior to the smartphone era. And Columbia probably has a higher percentage of cell phone owners than most cities, thanks to the young population and urban geography.

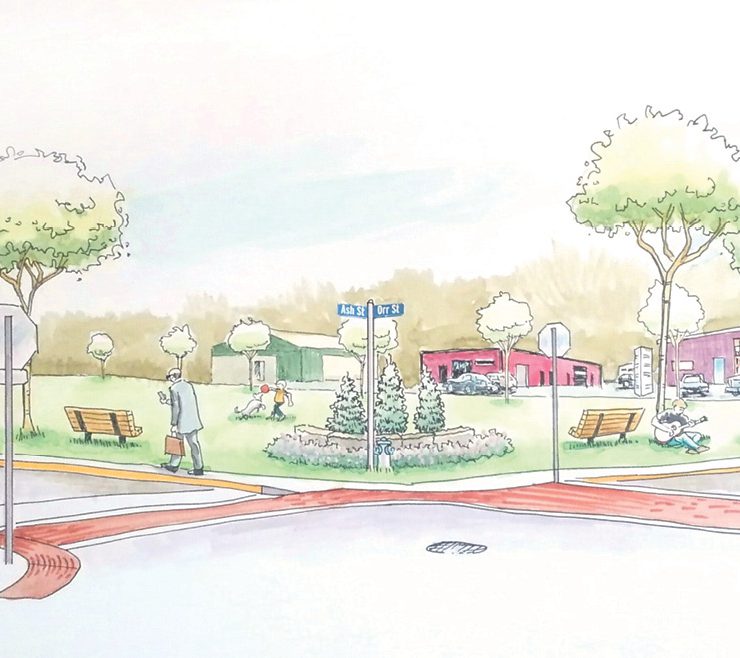

The community policing approach has been in use in Columbia for decades in various forms. However, the most recent incarnation, the Community Outreach Unit, consisting of eight officers and a sergeant assigned to three small, geographically strategic neighborhoods, has been successful both in building partnerships with citizens in those neighborhoods as well as reducing calls for police service. This achievement is particularly important, given that Columbia has the highest emergency call volume for police service of 26 comparable cities.

However, the Community Outreach Unit has come at a price that some inside the police department feel they cannot afford. The traffic unit and downtown unit was reduced in size, and the department has the same number of detectives today that it did in 1994. Some of those detectives carry caseloads in the 70s. Patrol supervisors who attempt to triage the calls regularly describe the situation as “ridiculous” on busy nights.

Officers frustrated at months of running from call to call with no discretionary time to follow up or proactively police their beat leave the department or become disillusioned with the profession as their discretion and decision-making is reduced to report taking.

Having a police department outgrown by its city leads to bad results. For example, officers taking reports on incidents they don’t have time to follow up on leaves criminal behavior unchecked and criminals enabled, resulting in lower quality of life for residents, especially in neighborhoods with low social equity.

The resource commitment to the Community Outreach Unit by the chief, the city, and the police department has been considerable. On February 19, the council voted unanimously on a resolution directing the city manager to construct a transition plan, timeline, and budget for transitioning the entire police department towards a city-wide community-oriented policing program. The report to council will be a collection of evidence, data, and templates for community oriented policing. It could shape the future of policing in our city. CBT