The Guardian of Every Other Right

What does it mean to “own” something?

For centuries, the system of law that built up first in England, then in America, has defined property ownership in terms of the right to make a range of decisions about and to control the use of a particular asset. The person (or group of persons) who ultimately has the authority to make these decisions is said to be the owner of the asset. In this legal tradition, the ability to own and enjoy private property is the foundation of independence. Former British Prime Minister William Pitt said, in 1763, “The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the crown. It may be frail, its roof may shake, the wind may blow through it, the storm and rain may enter, but the King of England cannot enter.” Shortly after the American Revolution, Arthur Lee, of Virginia, said, “The right of property is the guardian of every other right, and to deprive the people of this is in fact to deprive them of their liberty.”

The idea of private property is also deeply embedded in our constitutional framework. Both the U.S. Constitution and the Missouri Constitution forbid government officials to deprive citizens of their property without the due process of law. Courts have long recognized that a person’s right to property included the “free use, enjoyment, and disposal of” the things he or she owned. The Missouri Supreme Court has described the right to private property as including “ownership, possession, and the right to use in enjoyment for lawful purposes.” Thus, put in a very simple way, Americans in general — and Missourians in particular — have a fundamental right to purchase property and then to use that property in a manner that the owner believes best suited to promote his or her own happiness or well-being, so long as that use does not violate the law or endanger others’ health, safety, or quiet enjoyment of their own property.

Over time, however, courts have allowed more and more government interference with citizens’ rights to use and dispose of their private property. Sometimes this has occurred in the form of the government assuming ownership of property that previously belonged to a citizen in such cases as eminent domain or asset forfeiture. And other times it has occurred in the form of the government using regulations to strictly limit the ways in which private property owners may use their property. As long as these infringements were limited to instances in which the government would put the taken property to a true public use (such as a public road or a public building), or where the government was attempting to prevent potential dangers to the public health or safety (such as pollution, fire hazards, or vermin), the infringements do not conflict with constitutionally protected property rights. But governments both nationwide and here in Missouri have long since gone beyond appropriate constitutional limits; they now act as though there are no constitutional limits on government power to control who owns property and how citizens may use their property.

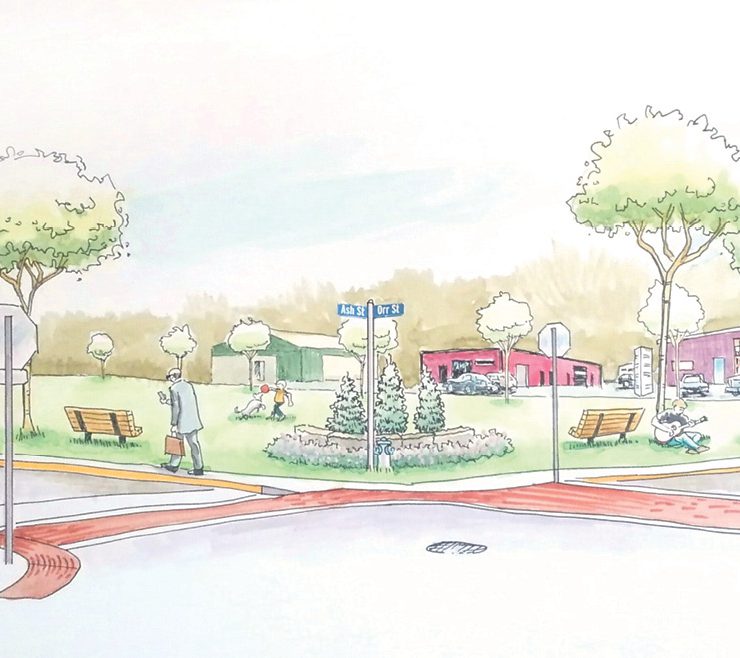

These restrictions most frequently work to the disadvantage of poor and minority communities. In the mid-20th century, communities began using eminent domain to displace minority-dominated neighborhoods and business districts, such as Sharp End here in Columbia, not because the government intended to put the condemned properties to “public use,” but instead to put the properties in the hands of different private owners. Although the use of eminent domain in Missouri has not been as blatantly racist in recent years, communities still frequently see it as a tool to remove poorer residents or businesses and replace them with a “better class” of citizen.

But even relatively affluent communities are increasingly willing to restrict property rights as a way to ensure a Stepford-esque homogeneity among residents. For the past four years, the city of St. Peters, Missouri, has been fighting in court for the power to impose hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines and decades of imprisonment on two senior citizens who committed the horrifying offense of growing perfectly harmless, perfectly lawful flowers instead of devoting half of their lawn to growing turf grass. The homeowners are allergic to grass and believe that the U.S. and Missouri constitutions protect their right to choose for themselves what lawful plants they will grow on their property. The City has admitted that the couple’s yard includes ample ground cover that from a distance would appear to be grass, but because it is not the type of plant the city mandates, the city insists that it must be able to punish them for their non-conformity.

Property rights really are the guardian of every other right. If we are to remain a free people, we must demand that our governments respect citizens’ rights to purchase, keep, and use their own private property for all lawful, harmless uses. After all, if we will not work to protect our neighbors from eminent domain abuse and nonsensical regulation, it’s just a matter of time before we lose our own rights.