The Changing of the Guard

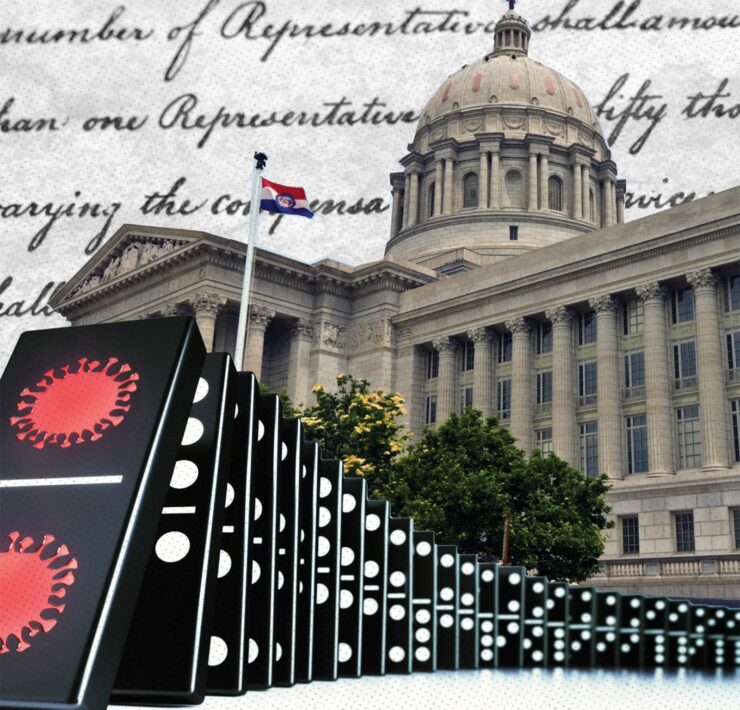

A new legislative season began in Jefferson City in January with familiar faces in unfamiliar places. The resignation of former Governor Eric Greitens at the end of May 2018 set off a chain reaction that has replaced most of the statewide office holders. Last year delivered a different governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and state treasurer . . . all without the benefit of ballot action.

At this writing, Missouri still awaits the decision of the Missouri Supreme Court on the constitutionality of the appointment of Mike Kehoe as lieutenant governor, who replaced Mike Parson, who replaced Greitens.

On December 19, 2018, Parson named southwest Missouri State Representative Scott Fitzpatrick to replace Eric Schmitt as state treasurer. That job came open with the appointment of Schmitt to replace Josh Hawley as attorney general after Hawley was elected to the U.S. Senate. (Are you dizzy yet?) If 2019 delivers nothing more than stability, it’s a plus.

Right now, the spotlight falls on the transition from Hawley to Schmitt as the attorney general. The question as yet unanswered is how much tinkering Schmitt will do to the structure and priorities of his new office.

When Hawley took over two years ago, the attorney general’s office changed political party for the first time in a quarter century. The Republican had campaigned on a promise of reorganization. But in recent weeks, published reports have detailed problems with management and morale.

By most accounts, Hawley raised eyebrows by scrapping an entire division devoted to environmental law and by turning over senior responsibilities to young lawyers who had worked on his campaign. And he leaves the office under the cloud of an official investigation by Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft over claims that Hawley violated state laws by allowing his outside campaign consultants to sit in on office staff meetings and set agendas for taxpayer-paid personnel.

If Schmitt, then, is inclined to scale back, it likely would not surprise anyone. But he sits down at the table with a full plate in front of him.

The office ends 2018 with nearly two dozen high profile initiatives, investigations, and lawsuits pending. The state of Missouri is suing big pharma over the proliferation of opioid drugs. A trial over claims that manufacturers have put consumers at risk is still more than a year away. The attorney general is still in a battle with Backpage.com over whether the site’s willingness to publish adult personal ads promotes human trafficking. (Missouri has beaten back a federal First Amendment lawsuit and now seeks criminal and civil sanctions against the website and its lawyers.) The attorney general’s office also has taken the St. Louis Housing Authority to court over claims that public housing has become substandard.

At this writing, the state still awaits a court ruling on its claims against Ripley Entertainment and Branson Duck Vehicles, the companies that operated the boat that sank last summer in Branson, killing 17 people. (Missouri’s suit claims that the operators misled customers about the risks of duck boats.) And, on December 14, on the eve of the 2018 deadline to sign up for medical coverage under the Affordable Care Act, a federal judge in Texas struck it down as unconstitutional in a lawsuit to which Missouri is a party. Schmitt faces a decision of whether to remain involved when, as senior Democrats have promised, the case goes forward on appeal.

At the same time, the Hawley staff has opened high profile investigations of Google, over the collection and use of consumer data, and of the Catholic church in Missouri, over its handling of claims of child sexual abuse by clergy. The latter is complicated by the attorney general’s lack of subpoena power, a situation which Hawley complained hampered his probe last spring of the use of a message-deleting app by the Greitens’ staff. During that investigation, Hawley said he wanted to change the subpoena policy through legislation.

Schmitt must consider these priorities, along with Hawley’s initiatives to combat human trafficking, to provide legal assistance to military veterans, to eliminate a backlog of untested rape kits, to rein in robocalls, and to change the administration of the legal expense fund that pays successful discrimination and human rights claims against state agencies. (Hawley believes the law should be changed to require those agencies to absorb at least a portion of those claims in their operating budgets, providing an incentive to change bad behavior.)

In early December 2018, Hawley and Schmitt made a public show of the transition process by inviting capitol reporters to sit in on a briefing of the Schmitt transition team by the Hawley senior staff.

Hawley was more gregarious in his presentation. Schmitt was more measured in his responses, making no specific commitments on office organization, staff, or projects and priorities. He has talked about maintaining the fight against federal government overreach and about a greater emphasis on combating crime.

Toward that end, just before Christmas, Schmitt named Tom Albus, a federal prosecutor in St. Louis who has spent that career chasing fraud and corruption, as his first assistant attorney general. Overall, Schmitt told reporters he will put a priority to the continuity of service. (See paragraph 3, “stability.”)

Kermit is an award-winning 45-year veteran journalist and one of the longest serving members of the Missouri Statehouse press corps.