Opinion: A Wasted $15 Million

August 30, 2018

Their spiels to the public were confusing but convincing. Many petition signers — some barely old enough to vote — probably had no idea what they were affixing their signature to. To them, it was likely just another petition like the one they signed a few weeks earlier regarding medical marijuana.

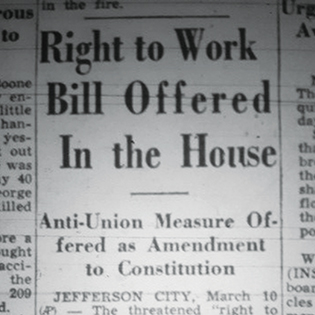

Proposition A came up a cropper — failed miserably — this election just like it did in August 1978. The outcome was pre-ordained, bought and paid for with a flood of money — more than $15 million by one estimate — and a gazillion yard signs spread across the state. Defeat was never in doubt.

Opponents to the proposition claim the right-to-work law is “Wrong for Missouri.”

Well, that’s their opinion.

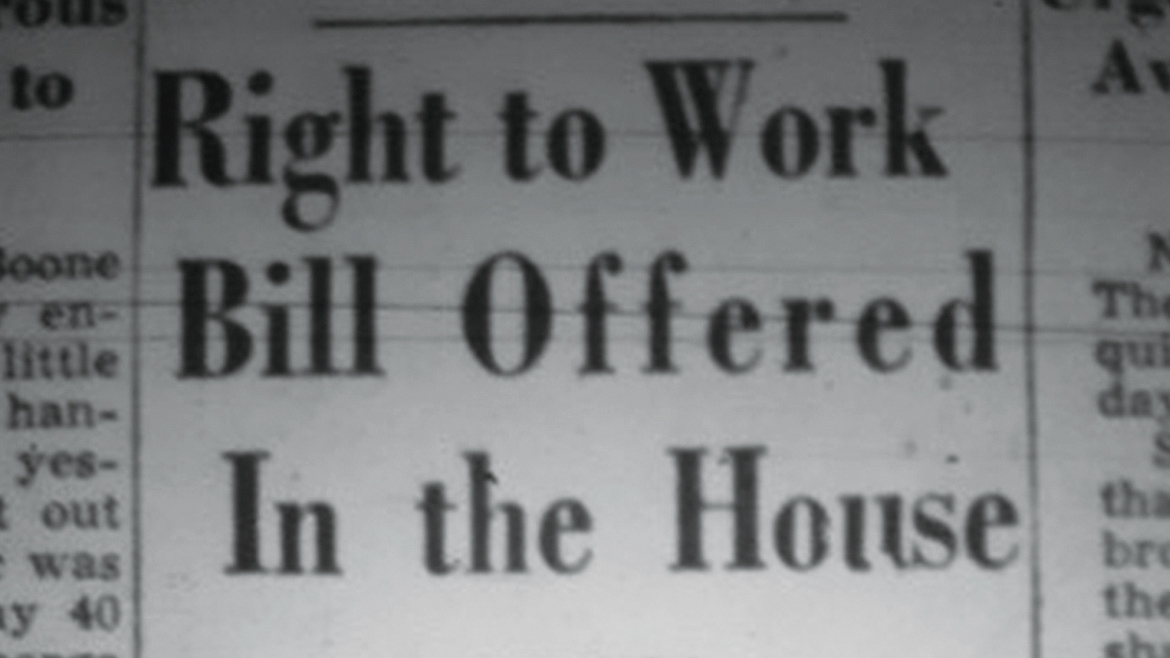

A right-to-work law for Missouri would have invoked section 14(b) of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, also known as the Labor Management Relations Act. This would have exempted employees from having to pay union dues where co-workers bargained collectively in a closed shop setting under provisions of the National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act of 1935.

In what was billed as “Wrong for Missouri,” in fact, could have been right for the Show-Me State.

A right-to-work law might have brought more business and industries to Missouri. More jobs. More revenue from taxes to relieve and rejuvenate tight budgets across the state.

The defeat of right-to-work was a pyrrhic victory for organized labor. Over the long term, many unions have been defanged. Union membership has plunged from 25% of the workforce decades ago to historic new lows — in the single digits, by most estimates.

Labor peace is widespread. Strikes are a rare occurrence these days because public sector workers are generally forbidden to strike and, therefore, inconvenience the public. And the public is also hardly ever inconvenienced by the demands of organized labor because labor and management seem to be able to work things out.

Both sides are at peace. Columbia’s major private sector employers remain immune from unionization. It’s in the government and education fields where there’s any sign of the employee versus employer testiness that often breeds unionization.

Organized labor and its allies spent more than $15 million to fight against right-to-work this go-around. This time they won fair and square. But the $15 million could have been invested by organized labor for job training and enhancement, programs for minorities, young people, apprenticeships, and health and pension plans while buttressing many of the other great benefits organized labor has brought to the workforce over the years.

What a waste.

Tags