Legal Impact

September 3, 2010

Weekends around midnight at Club Vogue, dancers are used to baring it all before a big crowd. A few blocks down Business Loop 70 at Passions Adult Book Store, clerks are used to doing their best business.

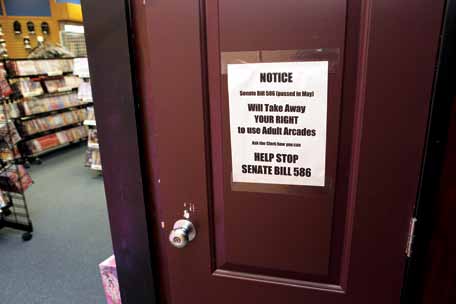

Shortly after midnight last weekend, when a new state law restricting adult entertainment businesses went into effect, the dancers could only strip to their bikinis, and most of the seats at Club Vogue were empty. Passions was empty of customers because the law now requires the doors close at midnight.

The Cole County judge who denied a suspension request on the eve of the law’s enactment acknowledged that sexually oriented businesses in the state “will likely suffer some economic loss.”

His prediction came true, at least in the Columbia adult-oriented businesses that reacted by laying off workers, though the extent of the impact is uncertain as the legal challenge continues.

City police officers, however, doubt the veracity of predictions made by legislators advocating the restrictions — that the new law will reduce prostitution and illegal drug activity.

In the meantime, the adult business market is adjusting to the new rules.

“Our plan is to stay and open and hopefully remain profitable,” Club Vogue owner Jay Yeager said. “It’s going to be a tough road, but we’re going to give it a shot.”

Yeager tried to make the most out of the final nights of full nudity. He hired people to stand at busy intersections nearby and whirl signs advertising his “gentlemen’s club.”

Shortly before the new law went into effect, the club had been busier than usual, said Passions owner Nellie Symm-Gruender. Her store sells lingerie along with adult films and novelties, so she was in one of the city’s two strip clubs to sell skimpy outfits to dancers performing after the clock struck 12 on Aug. 29.

The disc jockey encouraged patrons to purchase lap dances from the dancers while the state would still allow nudity at the club. A fully nude platinum blonde dancer finished her act and collected the cash tips patrons left on the edge of the stage.

When midnight hit, Yeager said, there was an almost “instantaneous effect.” The next dancer came to the stage and wore a bikini that would stay on for the entirety of her act, and many patrons hit the door.

The patrons who remained were mostly young men sipping on water and sodas. (The club has no liquor license and used to have a bring-your-own beverage policy but now requires its patrons to purchase nonalcoholic beverages after paying the cover charge if they want to stick around.)

Yeager said he lost 50 percent of his normal business on the first night that dancers were forbidden to appear nude in his club. As for the dancers there, he said his best guess was that they made 70 percent less than their usual income. Yeager let two of the dancers go before the night even got started because, the owner said, business has been slowing since word got around that nudity would soon end.

Considering that night’s meager turnout, Yeager said more of the club’s entertainers could be expected to find other jobs.

“It’s very sad for me, as an employer, to call an employee and say, ‘Sorry, you don’t have a job,’” she said.

Symm-Greunder’s company, which also operates stores in Boonville and Marshall, is one of 17 plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed with the intent to stop the law from going into effect. A Cole County judge denied the plaintiffs a temporary restraining order on Aug. 27, and on Wednesday the Western Missouri Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s decision.

Yeager said that as long as the law remains in effect, he expects business at the club to worsen. “If we’re not granted some sort of relief,” he said, “we may very well go out of business.”

The Missouri House approved the regulations 118-28. Columbia Democrats Chris Kelly and Mary Still voted in favor of the restrictions. The proposal was approved with a 27-4 vote in the Senate on the same day, with the support of Kurt Schaefer, R-Columbia. State Rep. Stephen Webber, D-Columbia, was the only Columbia legislator to vote against the bill.

Symm-Gruender and the other plaintiffs in the suit challenging the law took issue with language describing the “secondary effects” inflicted upon society by the mere presence of sexually oriented businesses.

Columbia Police Department Public Information Officer Jessie Haden said most of the department’s prostitution arrests occurs in hotels and motels and usually consist of law enforcement officers arresting prostitutes after they have been contacted through personal ads posted on Craigslist or printed in local publications.

“If there are prostitutes just surrounding my store,” Symm-Gruender said, “why aren’t there police out there arresting them?”

Arrests for prostitution, which include promotion as well as participation, have been on the decline in Columbia for the past four years, according to figures compiled by the Statistical Analysis Center of the Missouri State Highway Patrol. In 2006, there were nearly 1,100 arrests for prostitution and its promotion. Last year, there were 568, and halfway through this year there have been 168.

The arrests do not typically occur, Haden said, at strip clubs in Columbia or in the areas nearby — nor are these areas more prone to crime than most areas across the city.

“That’s just not true,” Haden said. “That’s just a fallacy.”

Columbia Police Officer Tim Thomason, who has been working prostitution cases for 10 years, said a small number of sex workers arrested in prostitution stings sometimes also work for local strip clubs, but he said these dancers have taken up prostitution on a freelance basis, and local club owners have been cooperative with police.

“To say that our strip clubs are causing prostitution and drug activity,” Thomason said. “That’s a pretty far stretch I would think.”

Symm-Gruender and the other plaintiffs in the case claimed that their First Amendment rights to free expression are compromised by the new state statute.

They also claimed members of the state legislature had violated the state constitution by refusing to grant a representative a requested hearing on the potential costs of the bill for the state and that the law would have significant financial impact on their businesses and on state coffers, which receives tax revenue from the businesses.

“It’s lose, lose, lose for the citizens of Missouri,” Symm-Gruender said. “It’s pure and simple.”

But the Missouri Attorney General’s office, the defendants in the case, argued that that rule was procedural and essentially left to the discretion of the legislature.

“They (legislators) are entitled to follow the rules or not follow the rules as they see fit, as long as the rules are their own,” said Ron Holliger, a general counsel for the Missouri Attorney General’s office.

The attorney general also argued that the plaintiffs do not have grounds to claim a violation of their First Amendment rights because the government can regulate speech in terms of its time, date and place, and the government can take steps to limit the “secondary effects” caused by those businesses. Cole County Judge Jon Beetem said the plaintiffs had not demonstrated the burden of proof necessary for him to grant a restraining order.

Symm-Gruender said Passions had discontinued use of its privacy booths at its Columbia store before the law had gone into effect.

At Club Vogue, because dancers will be clad in bikinis, they will be able to circumvent the law’s restrictions on contact between patrons and entertainers, and dancers will still be allowed to give lap dances, which Yeagar estimates accounts for about a third of the business in the club.

He said that getting a liquor license for the club is an option that is “on the table,” but that would force him to comply with another set of regulations that would force the club to cut its hours short on the weekends and limit contact between patrons and performers.

What's Your Reaction?

Excited

0

Happy

0

Love

0

Not Sure

0

Silly

0