COVID Reflections

- "COVID Reflections" originally appeared in the March 2025 "Work" issue of COMO Magazine.

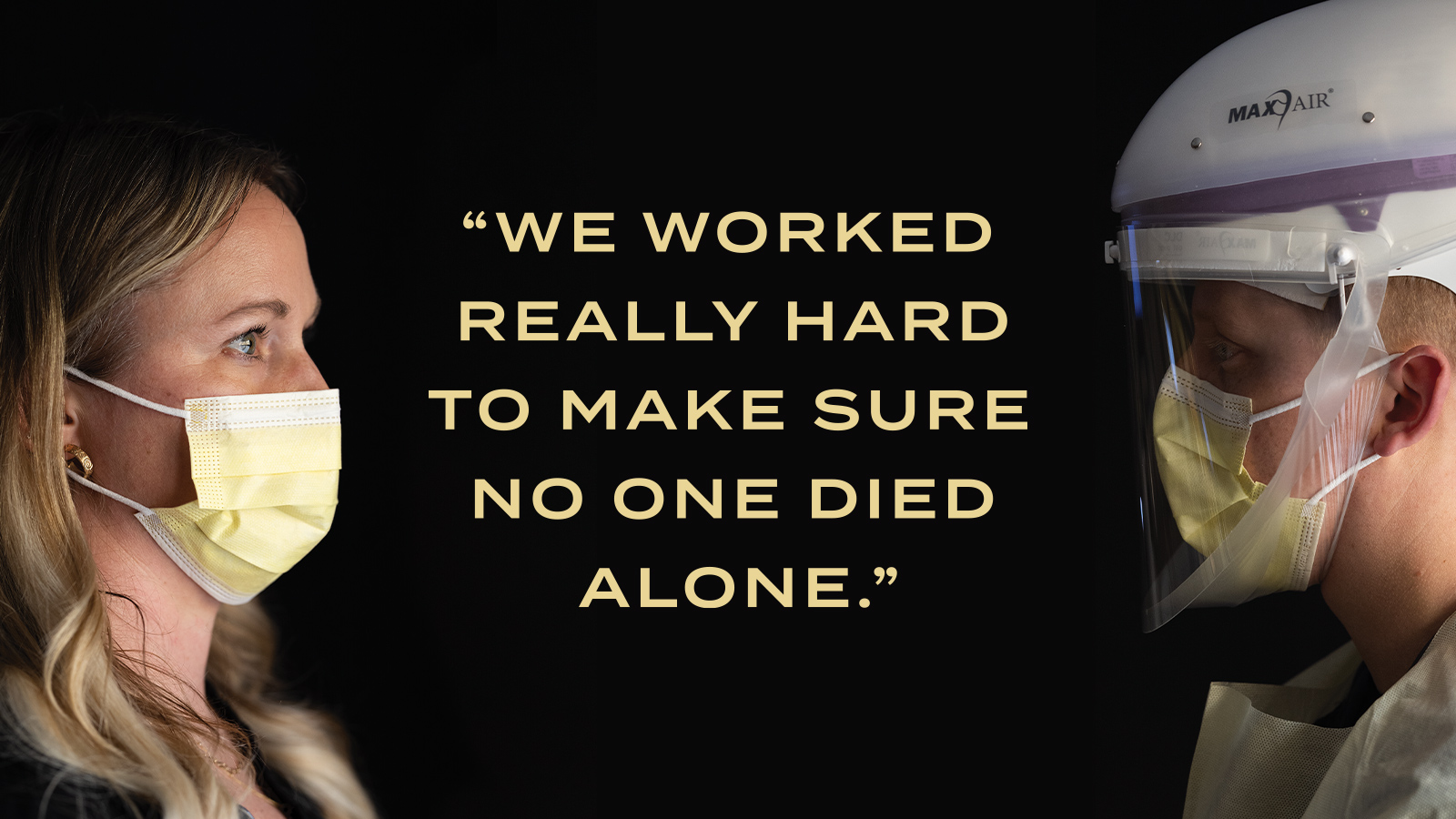

Columbia nurses recount pandemic experiences.

People didn’t believe that COVID was real and that so many people lost their lives because of it. It really downplayed the lifesaving work we were doing.

– T.J. Headley, RN

In the first days of the COVID pandemic, when all the COVID patients were moved to one area of the intensive care unit at University Hospital, the staff there was isolated from the rest of the hospital.

That quickly became the standard protocol.

“We called it COVID Cove,” MU Health Care RN Heidi Baybrook recalled. “Someone always had some music playing in the background and it helped ease the uncertainty of the unknown. I think that time period helped to really build our teamwork.”

That teamwork, each medical professional’s skills, and the overall resilience of the team and individuals would be tested as Columbia’s two hospitals grappled with the worldwide pandemic that officially began on March 11, 2020.

Looking back five years later, four local registered nurses (RNs) responded to an email questionnaire from COMO Magazine, seeking their personal insights and perspectives on being an ICU nurse during the pandemic. Baybrook said her profession, which is experiencing a nursing shortage nationwide, is still in recovery — in more ways than one.

“I was in survival mode and not even aware of it for pretty much the entire time,” she explained. “It wasn’t until after the pandemic that I was talking to a nurse from a different department, and she told me I had to figure out how to participate in everyday life again and do the things that would rebuild me to being ‘Heidi.’ It’s actually been slow going. The experience was life- changing and I can’t think about COVID days without feeling profoundly exhausted and empty.”

Wanting to do something ‘bigger’

Understanding the psyche of the nurses who also became de facto therapists, housekeepers, and other additional roles might require plugging into the motivations that put them on a path to become a nurse. For Sara Wilks, an ICU RN at Boone Health, her reason for pursuing a nursing career is not uncommon: Memories of a relative receiving care or a parent having a medical background.

“I also have memories of my grandmother receiving home health and hospice in her last years, and the connection and the gratitude for the work and care these nurses provides was invaluable,” Wilks said.

Baybrook was first a cosmetologist before pursuing a nursing degree, first at Columbia College and now at Mizzou.

“I wanted to do something bigger and find something that gave me more fulfillment,” she said, explaining that her next step was to complete her BSN degree at MU.

MU Health Care RN T.J. Headley watched his mother battle cancer and chose to become a nurse “to help others and make a positive difference in others’ lives.”

That common denominator would make a difference in their own lives, too. Wilks agreed, adding that remembering the early days of the COVID pandemic and trying to isolate specific moments is challenging.

“It all feels like one long fever dream,” Wilks said.

Crying in the darkness

The “this can’t be real” moment for Wilks hit her after watching news reports of the pandemic gripping Italy and seeing healthcare workers with their faces creased by the N95 respiratory masks.

“We had no real context to gauge how this crisis would pan out,” she said. “I remember waking up one night and going out to my living room to cry because I was so afraid of being separated from my family and forced to live on site at the hospital or a designated living space for those who were chronically exposed, such as healthcare workers. We just didn’t know what would happen, which leaves the mind to create some real doozies in way of scenarios.”

For Baybrook, as for most nurses, she said, there wasn’t a single “this can’t be happening moment,” but a more brutal, drawn-out period where the virus and the accompanying lockdown and rampant misinformation played out over time.

“I had a seven-week stretch where every patient I cared for died, either on my shift or they were gone when I came back,” she said. The pain was multiplied by the tragedy caused by visiting restrictions.

“We had a lot of patients die without their families, due to visiting restrictions or family members being afraid of getting sick as well,” she said. “We worked really hard in our unit to make sure people didn’t die alone.”

Headley can relate to that memory.

“We lost a lot of patients,” he said. “Most were in the ICU alone during that time. It was very hard for nurses, and it was hard for families to not be there.”

‘Gross misinformation’

Morgan Nistendirk, BSN, RN with MU Health Care, recalls the “everything has changed” moment was when an entire side of the ICU was cordoned off to begin admitting COVID-positive patients and those who were being tested.

“One day we walked into the hospital, and everyone entering had to have their temperature taken at the door,” she added. “Working in the primary ICU that housed COVID patients, we were isolated from the rest of the hospital.”

There were life-and-death, compelling scenes that played out countless times out of public view. Yet the reality of what was happening sometimes was overshadowed by what Wilks referred to as “the gross amount of misinformation that was being spread from social media and exacerbated by the administration in power.”

Baybrook echoed that stance.

“There was so much misinformation throughout the pandemic, so many changes that post-COVID nursing is really having to work to build the trust of the patients, and reaffirm that we are on their side and want to be an advocate for them and honor their wishes,” she said.

Wilks continued, “One of the worst parts, for me, was dealing with those who felt they knew more about the realities of COVID and what was happening ‘behind the scenes’ than those who were living it in real time. The conspiracies [theories] were hurtful and curated in fear and distrust in a time when we needed to support each other, however it felt like it became another thing to politicize and divide us.”

Headley said that was “another paint-point for nurses.”

“People didn’t believe that COVID was real and that so many people lost their lives because of it,” he said. “It really downplayed the lifesaving work we were doing.”

Heavy weights

Wilks said the experience is hard to convey to anyone who has never worked or been in the ICU, “let alone during a pandemic.”

“Emotional burnout was huge; the witness of suffering can take its toll,” she said. “It truly is like being in war … some of us detached from the trauma so we could continue to move forward, which makes remembering it all difficult at best.”

Baybrook added, “I remember thinking, ‘I just want to see someone get better and leave alive.’”

Yet the most painful memories are important to convey, Wilks added.

“Long shifts, constantly changing protocols, and staffing shortages became the norm,” she said. “The trauma of watching patients die, often isolated from their families, weighed heavily on nurses and doctors.”

Baybrook recalled a “steady and constant” reality of “patients dying, their room opening up, and a new one coming in, and you just kept repeating the process.”

The experience gave nurses an appreciation for each other and their teams.

“Our unit had fantastic teamwork, and everyone was so good about making sure nobody else was drowning,” Baybrook said. “We had a most supporting leadership team.” She also lauds the work of respiratory therapists, doctors, and others. “They were also good about checking in with us to see how we were coping.”

The unsung heroes

Those medical professionals were among the unsung heroes of the pandemic, the nurses said, specifically spotlighting respiratory therapists and the doctors.

“Respiratory therapists do not receive enough credit and appreciation,” Baybrook noted. “A respiratory therapist was critical to the patients’ survival and progress.”

She said doctors also worked hard, missed family events, “and sacrificed as much or more as nurses.”

“They also carried a tremendous weight of wanting to save their patients … They listened to sobbing family members, were hands-on helping us in the moment — on top of managing the care for so many critically ill patients,” Baybrook said.

Nistendirk wants history to remember those heroes.

“Physicians, respiratory therapists, and nurses were not only doing their jobs but also acting as family support to patients at the same time, since no one was allowed to visit in the beginning,” she said, adding pharmacists, pastoral care, case management, housekeeping, and transport services to that list. “There were weeks that felt like you were just running on autopilot since a lot of patients admitted with COVID required the same care in the sense they would all be placed on the same type of medications or therapies.”

Nistendirk is also adamant about the harsh reality of the pandemic and knows there might still be those who believe the pandemic was “created” or “made up.”

“A fact that cannot be disputed is that a lot of people passed away,” she said. “And I believe the number of lives lost during those years is easily just a number to many people.”

Photos by Anthony Jinson