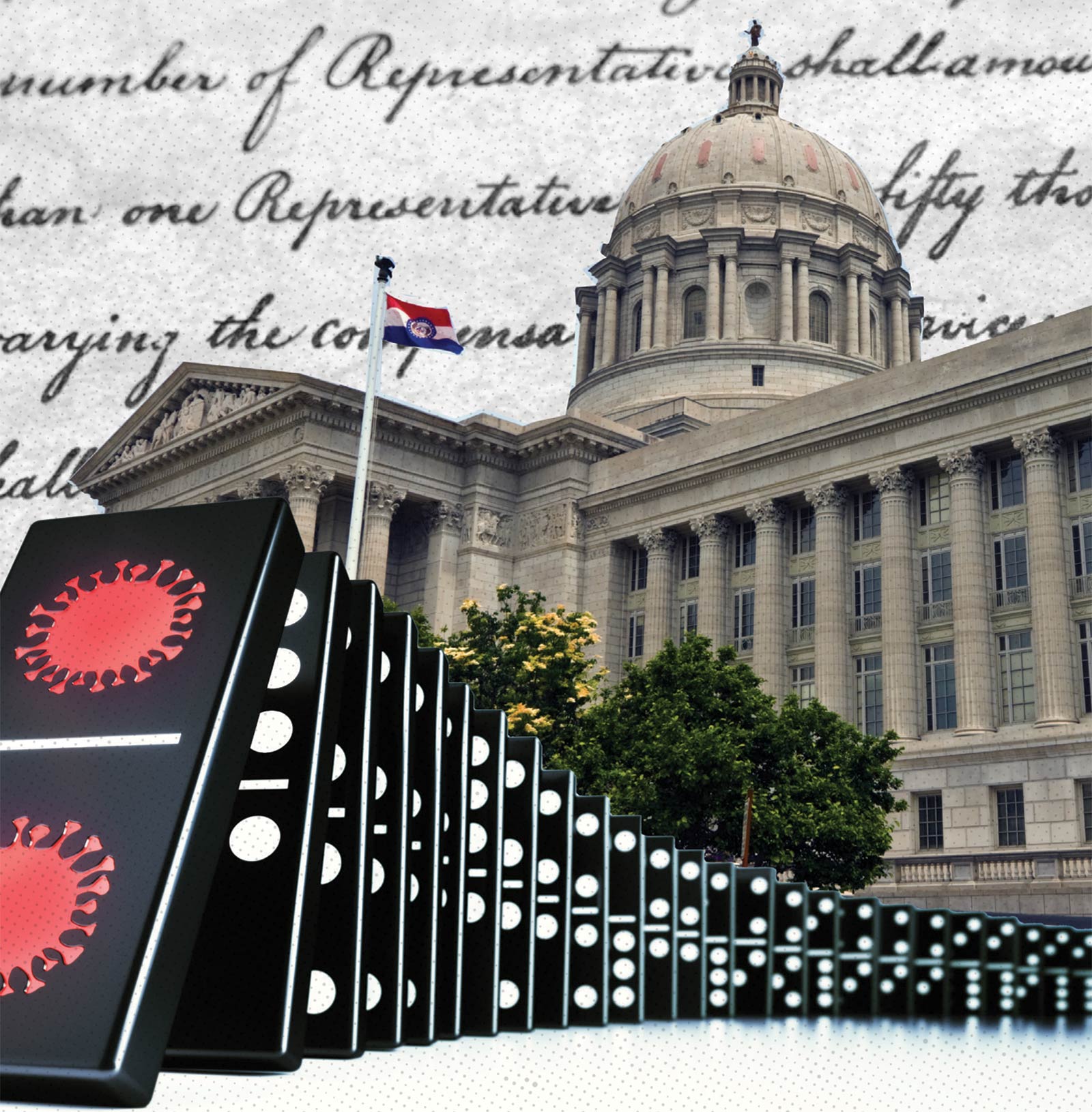

New Year, Unfinished Business

Reviewing unfinished policies and laws that began throughout 2020.

Under ordinary circumstances, a long off-season break (with an intervening election) would create a sense of anticipation at the state capitol. Returning veteran lawmakers and newcomers alike would look forward eagerly to a new legislative session opening in January. But the COVID-19 pandemic, which first delayed the conclusion of the 2020 regular legislative session, and Governor Mike Parson’s decision to call lawmakers back to Jefferson City into special sessions twice over the summer and fall to deal with COVID issues and urban violence, might have tempered (if not robbed) those who write the laws of their desire to jump back into it.

Nevertheless, the 101st Missouri General Assembly will open January 6, 2021, and lawmakers have pre-filed some-600 bills to address new concerns, long-standing issues, and unfinished business from 2020.

The unfinished business is likely to attract immediate attention, in part because of the manner in which it was left unfinished. Parson had summoned lawmakers to address the potential liability faced by health care providers who treat (or who choose not to treat) COVID patients, plus business owners working to supply the war on COVID. The Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry had pushed hard for such legal protections almost since the pandemic began. Legislation was drafted and was being heard in committee when word came down the governor and changed his mind and wanted to wait until 2021.

“New language was dropped at the eleventh hour, for whatever reason, that really changed the whole dynamics of that,” the governor told me later. “And we were under a very strict time schedule with COVID . . . and this was more of a procedure that would have taken place in a normal session.”

That sounded a bit vague. “What was in that bill that he doesn’t like?” I asked Senator Ed Emery, of Lamar, who was handling the liability bill. “I don’t think there’s anything that he doesn’t like. I think his concern was the absolute lack of confirmation from the [house of representatives] that they’d seen the language and that they were okay with the language.” Lawmakers might be waiting to see if U.S Congress addresses the problem in the next COVID package, which still hasn’t been approved. Emery is term-limited and will not be back in January. Joplin’s Bill White and Parkville’s Tony Luetkemeyer have pre-filed the original Senate language for consideration in 2021.

The pandemic could drive several bills in the new session. Democrats in both the house and senate will make noise about bringing back early voting permanently, probably citing the positive appraisal of the state’s Republican secretary of state about the smoothness with which the pandemic voting law was put into effect. (“I think anyone has to look into this election, dig into the data, and say, ‘Would it be good to continue some of this?’” Secretary Jay Ashcroft told me a couple of days after the election.)

And there almost certainly will be scratching and clawing about the limits to which local governments can impose emergency rules on individuals and businesses. The decision by St. Louis County Executive Sam Page to close restaurant dining rooms saw significant pushback. St. Louis County Senator Andrew Koenig picked up the battle flag, pre-filing legislation to bar local governments from imposing such a rule for more than two weeks within a two-year period without the approval of the state legislature. “We live in a constitutional republic where we have separation of powers,” Koenig said during a news conference. “No one person should have the power to make law and shut our businesses down.” Koenig’s bill also would prohibit limits being imposed on in-home gatherings.

The special session at mid-summer addressed urban violence by targeting those who commit it; lawmakers steered clear of the questions surrounding police behavior. So look for police accountability legislation coming from Ferguson Senator Brian Williams, as well as St. Louis’s Steven Roberts, who comes over to the senate from the house, and Kansas City Representative Ashley Bland Manlove. Their bills would ban the use of no-knock warrants and chokeholds and track the use of deadly force with a requirement that police report all such situations to the attorney general. They also would require training on how to de-escalate volatile situations.

At the same time, conservatives will want more protection for police. Incoming Senator Rick Brattin, who served four terms in the house, has filed legislation to punish communities that go down the “defund the police” road and to step up the penalties for state workers who participate in rallies deemed to be “unlawful assemblies.”

Other pre-filed bills address everything from education standards to tax policy (look for another debate on whether to require sales tax collection on internet sales, the so-called Wayfair Tax).

And lawmakers will take another shot at sports betting in Missouri. Three senators, including Majority Leader Caleb Rowden, of Columbia, and house member Phil Christofanelli, of St. Peters, have re-filed sports betting bills they sponsored in 2020 — bills that appeared to have lived until the pandemic got in the way. Now, with sports betting already in place in the border states Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, and Tennessee, Missouri is losing revenue it desperately needs.

The legislation would legalize wagering through online services, through lottery vendors, and on casino boats. Arguments remain over how much to charge for applications, licensing, and taxes. The real debate, however, is still over whether to impose “integrity fees” — payments to professional sports leagues, such as the NBA and MLB. Traditionally, the money that goes back to those leagues is ostensibly to monitor their games for betting-oriented shenanigans. In fact, it’s little more than a royalty, and in Missouri, proponents have proposed to leave the integrity money in state coffers to maintain, repair, or build new sports venues.