Commercial construction rebounds, but needs skilled workers.

Ten years later, memories of the economy speeding towards a brick-and-mortar wall, fueled by a growing bubble of subprime mortgages, low-interest rates, and a glut of new homes, are a bit less painful for real estate developers and construction companies.

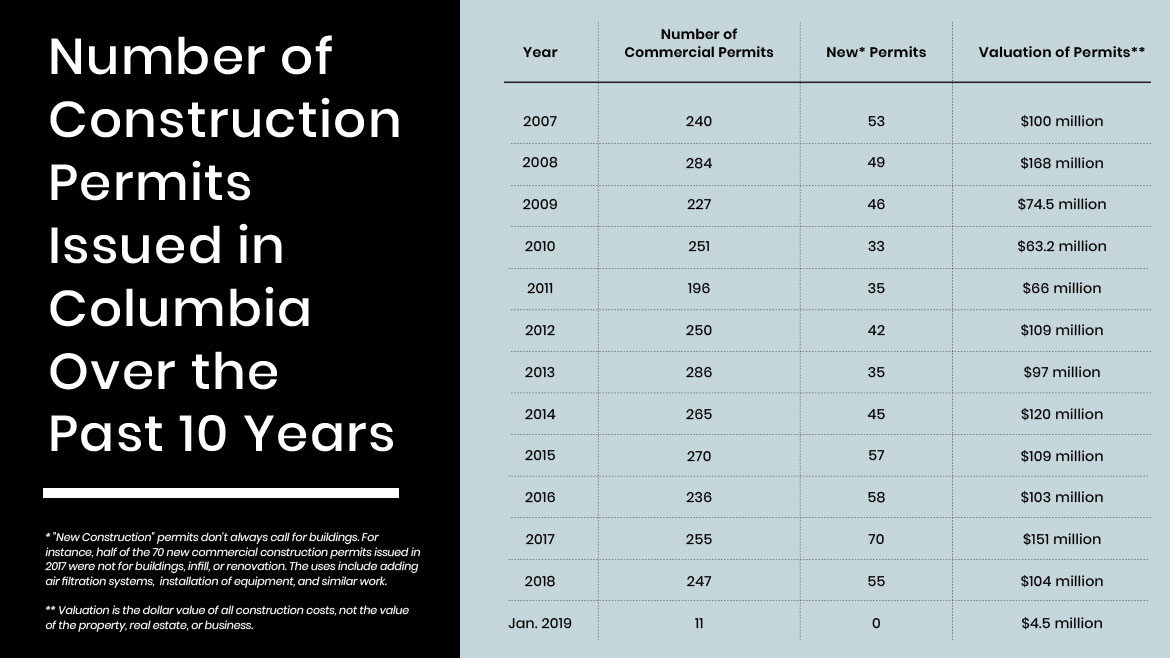

When the bubble popped and the Great Recession took hold in 2008 and 2009, few industries — other than the biggest banks and insurance companies — felt the seismic rumble more than the construction industry. Look at the numbers: The City of Columbia issued 284 commercial building permits in 2008, with a construction valuation of $168 million. (It should be noted that 49 of those permits were for new construction, but “new construction” isn’t defined as only a new building — it could be referring to a new air filtration system or installation of new equipment.) At the end of 2009, the number of commercial building permits totaled 227, and the valuation of only $74.5 million proved the cataclysmic effect of the bursting bubble.

A semi-steady stable of school, church, hospital, and government projects helped most construction companies, including Coil Construction, weather the storm. “They’re the saving grace for the industry,” says Randy Coil, owner of Coil Construction.

He says that, in 2008 and 2009, his company experienced a drop in work nearly parallel to the precipitous valuation drop, and although the volume of work has returned to pre-recession levels, another troubling wound from the bubble burst has not fully recovered.

“We had a lot of construction workers leave the industry,” Coil says. “More than any other industry. It’s what we’re seeing not just locally, but nationally.”

As the industry grapples with the labor shortage, especially among skilled workers, other aftershocks have rumbled, but not toppled, the industry.

Remember the tariffs last year, the first volleys of the Trump administration’s trade war with China, Canada, and a host of other countries? “There was a pretty good jump” in construction costs due to the tariffs, Coil says, “and not just steel.” But more on that later.

Retail construction has slowed, “for obvious reasons,” Coil says, listing the familiar litany of economic impacts of online shopping and e-commerce options, which compete with brick-and-mortar storefronts.

Though not on the same scale as the cost of tariffs, local builders and developers have also had to become accustomed to a new Unified Design Code, the city’s codification and revision of zoning regulations.

“It took us a while to get used to it — including the city,” Coil says of the still-new UDC. “We’re all working through that” and city staff seems to be making a concerted effort to arrive at “good, smart decisions with this new code,” he says.

Growing Pains

Building permit numbers and trends naturally tend to reflect the condition of the economy, says Tim Teddy, the city’s community development director. The valuation of commercial construction, though, has been more stable than the figures accompanying residential building permits. He echoed Coil’s observation that institutional commercial buildings — a new church, for instance — don’t add retail revenue, but those projects do contribute jobs.

Teddy also points out that looking at a period of permitting may not produce an eye-popping aggregate total, but one or two projects can recalibrate the picture in a positive direction — new projects like the burgeoning construction of a $150 million-plus plant for Aurora Organic Dairy.

And Columbia’s population continues to get a boost. The city’s estimated population in 2010 stood at 108,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, an increase of almost 30 percent from the 2000 census estimate. The 2015 census estimate was 119,108.

The increase for Boone County as a whole is just as dramatic. From 1980 to 2000, the county grew by 35,000 in population, an increase of 35 percent. The same level of growth — dramatic in the aggregate, but slow and steady on an annual trajectory at about 2 percent or higher — is continuing.

“We don’t have those wild swings” that bedevil the planning and growth of many areas, says real estate developer Paul Land.

It’s All Relative

Plaza Commercial Realty, Land’s company, has ridden the ebbs and flows of Columbia’s building and development economy as much as anyone. To gauge the market, they track the inventory of available space: office buildings and strip malls, professional spaces, and more. “Our vacancy rates are better in Columbia than they are nationwide. That means a healthy market,” Land says.

As far as new construction and new space, Land doesn’t put weighty stock on the number of permits that are issued. Like Teddy, he’s seen how one project — say, a medical building — can “tie up” one or more contractors for months or longer and “put a builder in high gear,” he says.

Land also cautions against looking at just permits and construction valuations to determine building options and costs. “There’s a bigger picture,” he says, not just construction costs that go into a business seeking to finance and plan construction. “If you want to add a 10,000-square-foot building and need one and a half acres, that’s a much harder item to find. And if you put something there, and it’s the wrong location, you’re going to be sitting on it a long time.”

Building and leasing activity might be a bit slow right now, Land says, but it is characterized differently by builders and developers who are busier. “The market is only bad if it’s slow for you,” he says.

Crunching the Numbers

What is the current level of building activity and how does it compare historically — at least to the past 10 years? First, it’s important to realize that commercial construction permits don’t have to be for new construction in order to have sizeable valuations. (Valuation listed on the permit is the value of construction, not the value of the property.) January 2019 passed without any permits for new commercial construction, but one of the 11 commercial alteration permits issued is for an addition to the PepsiCo production plant on Route B in north Columbia. The construction valuation: $2.3 million.

Permits for commercial alterations — which constitute most of Columbia’s commercial building permits — can also have hefty construction valuations. For instance, an interior remodel of the Aldi grocery store on the Business Loop has a valuation of $293,000. That permit was issued in November. There was only one permit for new commercial construction issued in December, but it was for a 4,000-square-foot build-out of retail space at Columbia Mall with a $251,000 construction valuation.

Beyond Bricks and Mortar

The best post-recession annual permit total was in 2017, with 255 commercial permits — 70 for new construction — with a valuation of $151 million, not far off the 2008 high of $168 million. Even though the volume of work has returned, the construction industry is pinched for skilled workers.

“Not all the folks came back” when the construction work picked back up, Coil says. “Also, generationally, we’ve lost a lot of craftsmen.” Not as many trades and skills are being passed down through generations, and there’s less entry into construction trades.

“We still have a lot of work to go around,” Coil adds, noting that construction has also become more technical, with GPS- or laser-guided equipment. “That’s been a good thing,” he says, because it has created a new level of technological know-how.

“I think as an industry we have not done a good job of marketing” and recruiting workers for the more technical jobs, he says. “It’s not as back-breaking as it was for your grandfather.”

Dollars and Cents

Now, about those tariffs on steel, aluminum, and other imported building materials. The total effect was an increase of as much as 50 percent for some materials, Coil says. Market forces also increased the cost of drywall (the gypsum was more expensive) and cement, but those increases seem to have plateaued and builders, suppliers, and developers are adapting. Things were a bit easier thanks to a lesson learned as a result of the recession. “They learned to stockpile less and deliver quicker,” Coil says.

As the industry learns how to respond and adjust to the steel and aluminum tariffs, price uncertainty will no doubt put contractors on heightened risk alert when bidding on projects. But tariffs alone aren’t responsible for higher construction costs, according to the Associated General Contractors. Diesel fuel, steel pipe and tube, asphalt paving mixtures, and aluminum products contributed to an overall 7.4 percent hike in construction material costs in the past year, AGC analysts determined.

Learning and Growing

While the economy’s cyclical nature keeps everyone on their toes, there’s equal focus on the city’s new zoning code, which has a learning curve that is especially steep for the downtown area, Land says.

Teddy agrees with that assessment. “We try to be as fair as we can in applying the code” while holding projects to the new provisions that are built on form-based zoning rules. He adds that not all the code is new. In fact, most of it isn’t, but it’s “kind of republished in a single package,” a look that engineers, builders, and developers aren’t used to seeing.

Coil isn’t convinced that the new code took out as much uncertainty from the previous rules as city officials intended, but he’s closely following how the still-new UDC is unfolding and being interpreted.

“We’re still light years ahead of everybody else,” Land says, repeating his observation of Columbia’s slow, steady growth, especially compared to surrounding communities around Boone County.

“They’re standing still,” he says, “so it looks like we’re sprinting.”