Remarkable Medical Miracles

The miracle of modern medicine lies in the eye of the beholder. Physicians are men and women of science who work to provide the most favorable outcomes for their patients. For them, medicine is about risks and benefits; they play the odds. Their training and experience teach them that treatments for most diseases evolve over time and that the real miracle is how far we’ve come.

Physicians also know that patients facing life-threatening or debilitating conditions seem to do better with an optimistic outlook. Some studies show that family support can increase the chance of survival; others recognize faith and optimism.

The following stories show both sides of the coin. They showcase incredible treatments that continue to improve patient outcomes. They also illustrate something less tangible. In the words of Albert Einstein, there are two ways to live: one as though nothing’s a miracle, the other as though everything is.

On a wintry night last February, 4-year-old Reece Borst told his mother that God was calling him to heaven. His mother shrugged it off. “We’re Catholic,” she says, adding jokingly: “I’ve decided he’s going to be a priest.”

It would take a whole lot more to rattle Tiffany Borst. Back in May 2009, she and her husband, Bob Borst, were confronted with every parent’s nightmare. Five hours after birth, Reece had been airlifted to Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics in Kansas City. Doctors there were concerned about severe mental and physical disabilities and said the couple might need to make a decision about life.

“Right before they put him on the helicopter, they let me hold him for just a minute,” Tiffany says. “I know they did that in case he passed away. It was that severe.”

Reece, the youngest of Tiffany and Bob’s four children, suffered distress at the end of what looked like a normal, full-term pregnancy. When Dr. Lynn Puckett, Tiffany’s obstetrician-gynecologist, broke her water, excess fluid caused a placental abruption.

“There was an 18-minute period of time when the baby was in distress,” Tiffany says. “We were talking about a C-section, but pretty soon it was too far into the delivery. When he came out, he was limp, he was purple, and he wasn’t breathing.”

Dr. Timothy O’Connor, a neonatologist specializing in premature and ill newborns and high-risk pregnancies, inserted an endotracheal tube. The procedure, known as intubation, provided an airway for Reece’s lungs, which had been drowning in fluid.

“Basically, they breathed for him,” Tiffany says. “They revived him. They wheeled him away, and my husband and I were so traumatized. We were in shock; we didn’t know what was happening. Dr. O’Connor came in and sat down, and I knew this was not good.”

O’Connor explained that Reece’s blood acidity was very high, which indicated that the placental abruption had deprived his body of oxygen, which could cause many organs to function abnormally early on. He told them about a new treatment at Children’s Mercy in Kansas City called hypothermia therapy, which cools the body, thereby decreasing the brain’s need for oxygen. The therapy would buy them time until his breathing could become normal.

“They said that we had a very small window of time, and if we didn’t do it right away, we would miss it,” Tiffany says. “For me, we had no other options. My husband had some connections to a NICU nurse in Kansas City, and we called her immediately. She said, ‘Do it.’”

The hospital staff packed baggies of ice around Reece’s head, and five hours after birth, the newborn was in the helicopter, hurdling toward Kansas City. Bob followed by car, scanning the evening sky for signs of Reece’s journey, while Puckett and Dr. Paula Stuebben, the Borst family’s pediatrician, checked on Tiffany, who was still at Boone Hospital.

“I was so grateful to them,” Tiffany says. “Dr. Puckett had been there all day, and Dr. Stuebben came by on her own time. All the docs at Boone went above and beyond.”

The next morning Tiffany’s father drove her to Kansas City. She and Bob, with their other children joining them later, stayed at the Ronald McDonald House, which Tiffany calls a Godsend. Ten days later, Reece’s vital organs were functioning properly, and he came home. The hypothermia treatment had saved his life.

But it was still unclear whether his brain would function normally. After a few weeks, the Borsts noticed that he wasn’t looking to the left, which indicated stroke-like behaviors. They called O’Connor, who referred them to First Steps, which provides therapies that can catch long-term problems ahead of time. With the help of a physical therapist and later an occupational therapist, Reece’s brain in effect developed new pathways during a critical time of development.

“Once he began walking, he was fine, and the funny thing is, now he’s probably my smartest kid,” Tiffany says. “Dr. O’Connor basically saved Reece’s life three times, in my opinion. There are so many miracles in this story.”

Over the past three years, Reece Raises Hope, a charitable organization set up by his aunt Barbara Simmer, has raised $18,000. Proceeds have funded a hypothermia treatment program at the University of Missouri Hospital and Clinics, Ronald McDonald House and the Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Columbia.

There’s a saying about the U.S. Postal Service: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their rounds.” Perhaps they should add cancer, too.

Mark Judy has been delivering the mail in Macon County, rain or shine, for 10 years. He also raises cattle, restores tractors and recently built much of his new home himself. He has rarely missed a day’s work, despite the fact that during half his tenure with the USPS, he’s undergone chemotherapy.

Judy is a cancer patient who has beaten the odds by a long shot. When he began treatment for colon cancer five years ago, the median survival rate for his condition was eight months. Since then, he has responded dramatically. Dr. Joe Muscato, his hematologist-oncologist, has never seen anything like it. He calls it a home run, one of a handful he’s seen during his 32-year practice.

In the summer of 2008, Judy began experiencing bleeding and changes in appetite. He finally went to the doctor the following winter after he also had pain in his upper right side. Results from a sonogram and CAT scan showed that his liver was massively involved with cancer.

Local doctors referred him to Missouri Cancer Associates, where Muscato learned from biopsies and other tests that the cancer had started in his colon. Judy began chemotherapy, and a week later, his symptoms had subsided. Muscato was surprised to see that his liver had shrunk as well. Since then, Judy has received 86 cycles of chemotherapy, more than Muscato has ever given a patient — or probably ever will again.

“It’s because it’s such an unusual situation,” Muscato says. “We don’t really know if the cancer’s suppressed or if it will stay away.” After consulting with a colleague at Washington University, Muscato decided on a five-year stopping point to see what would happen.

“I think I’ve been the topic of conferences because they’ve never seen this before,” Judy says. “We were at the point where we either had to stop the chemo or keep going on with it. My last treatment was on Jan. 13, 2014.” Muscato continues to follow up by monitoring his CEA tumor marker, which can be measured in the blood, as well as other tests and exams.

“Dr. Joe said we will have to deal with uncertainty,” Judy says. “It probably will show up somewhere, but it’s just something that you’ve got to deal with. Everybody’s asked if it bothered me, and I said it didn’t because I know where I’m going when I die. I think that the good Lord works through doctors, and everything that’s happened is through the power of prayer.”

Muscato supports Judy’s strong faith, which includes involvement in his church and community. He adds that Judy’s courtship and marriage to his wife, Jerri Ann, which all happened while he was on chemo, can be an additional source of strength.

“In general, support is very important,” Muscato says. “I always say, I’ll take it anywhere I can get it.” He adds that when it comes to battling cancer, research suggests that married people fare better than those who aren’t married.

A little comic relief now and then doesn’t hurt either. Judy says he’s always enjoyed joking around with the staff at Missouri Cancer Associates. “Dr. Joe’s pretty straight with me,” he says. “Me and him are both jokesters, so we have a good time with all this, but he’s pretty straightforward.”

At one point during his treatment, Judy’s CEA tumor marker had dropped by nearly half in just two weeks. Muscato gave him the good news: “Mark, I think you’re going to outlive the Post Office.”

It wasn’t too long ago that Dale Swoboda thought his bike-riding days were over. For years, Swoboda and a friend had been cycling 15 to 20 miles once or twice a week, but by last August, he couldn’t keep up.

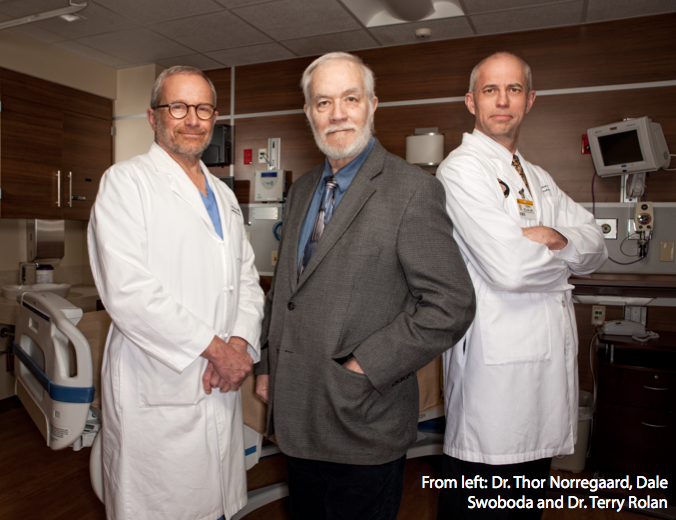

“My disease was beating me down,” he says. Swoboda, a core faculty member and co-coordinator of the School of Public Policy at Walden University, has Parkinson’s disease, a progressive disorder of the nervous system that causes tremors, muscle rigidity and slow, imprecise movement.

Swoboda’s symptoms began about three or four years ago when he started experiencing stiffness in his thigh, especially while driving long distances. Over time it spread to other joints, and he developed a tremor. Dr. Terry Rolan, a movement disorder neurologist at University of Missouri Health Care, diagnosed and treated him for essential tremor, the disease Kathryn Hepburn had. But a year later, Swoboda developed new symptoms. He needed more sleep than usual, lost his sense of smell, developed a false and expressionless face and became a bit clumsy. Rolan added the diagnosis to Parkinson’s.

“Right after I was diagnosed, I went to a wedding in Silicon Valley, and at the reception, I snuck out and cried for a half hour,” he says. “I had gone to see a counselor and brought up the fact that at some point all I could do is sit on the bench on the trail instead of ride, and that saddened me.”

With no cure for Parkinson’s, Swoboda relied on medications to improve his symptoms, but he knew that over time their effectiveness would diminish. Swoboda’s wife, Georgalu, with whom he wrote a textbook in 2008, researched options and learned about another treatment that offered hope.

“Dr. Rolan asked, ‘Have you ever heard of deep brain stimulation?’” Swoboda says. “My wife and I just smiled at each other.” Rolan explained that in the past, doctors hadn’t used DBS until later stages of Parkinson’s but were now getting results earlier. He warned, however, that DBS wasn’t a panacea and that Swoboda would do well if it alleviated all but his problems with balance and smell.

Deep brain stimulation, which was approved by the FDA to treat Parkinson’s disease in the late ’90s, involves two surgical procedures. During the first, a surgeon implants tiny electrodes in the brain’s subthalamus. The second surgery involves inserting a battery-operated device, similar to a pacemaker, into the patient’s chest. The device delivers electrical impulses to the electrodes, which stimulate areas of the brain that control movement. Experts believe that the impulses block signals that cause tremors, stiffness and other symptoms.

Swoboda says that he and Georgalu were bound and determined to give DBS a try. Rolan recommended Dr. Thor Norregaard, a neurosurgeon at MU Health Care, for the surgical procedures, which took place last fall. Norregaard has more than 25 years of surgical experience for tremor conditions such as Parkinson’s disease.

The initial procedure is not for the faint of heart. Because neither the brain nor the skull has nerve endings, and because Swoboda needed to be alert enough to respond to cues during the surgery, he received no general anesthesia. The medical team did numb his scalp, but Swoboda describes the experience as unnerving.

“When they drilled, it sounded like a jet plane taking off,” Swoboda says. “It was very loud, but I didn’t feel a thing.” He says he was secured to the operating table with what’s called a halo, a device that restricts movement of the head and enables surgeons to accurately place the electrodes without damaging the brain. The procedure took about four and a half hours. Two weeks later, Norregaard implanted the battery in Swoboda’s chest.

About a month afterward, Rolan turned on the stimulator and programmed it. He says that though Swoboda is responding well, he’ll need to make periodic adjustments to the DBS unit over time.

“The key to making the right adjustments that benefit the patient the most involves not only skill as a movement disorder neurologist but experience in programming these devices well,” he writes in an email. Rolan has been involved in programming deep brain stimulators since their initial use in the late ’90s.

Swoboda says that over the past six months, his fingers are more nimble, he doesn’t shuffle as much, he takes one pill instead of four and expression has returned to his face. He’s also back to riding his bike.

“The goal of the surgery is to stave off the symptoms, to make the progression slow way down,” he says. “We won’t know for several years if that’s the case, but it’s starting off great. My wife says I’m doing 70 percent better than I was. I’ll take 70 percent.”