Hope for Missouri-Made SMRs

UPDATE: Since the CBT went to press, Westinghouse has announced the redistribution of staff previously devoted to the development of small modular reactors. Although Ameren Missouri’s exclusive agreement with Westinghouse has expired, the company continues to consider its options moving forward—including keeping a close eye on how the companies that did receive government funding fare in the development of SMR technology.

In the heart of the heartland is Callaway County, Missouri’s second largest county at about 928 square miles. Hovering above the county’s patchwork of farmland is Callaway Nuclear Power Plant, the heartbeat of the county.

With a scattered population of 44,000, Callaway County may very well be the site of a potential worldwide manufacturing plant for small modular reactors, giving Missouri — and Callaway — a chance to shine.

Callaway Energy Center, built in 1984, allows for low electric rates to more than 750,000 households in the area, including larger cities such as Columbia. The rates are “much lower than national, lower than the Midwest and just about the lowest electric rates in the state of Missouri,” says Warren Wood, Ameren Missouri’s vice president of legislative and regulatory affairs.

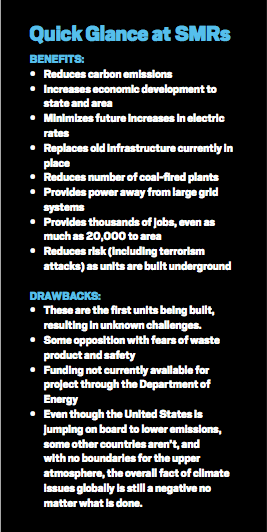

About 20 percent of Ameren Missouri’s power comes from Callaway; the remaining 80 percent comes mainly from coal-powered plants. The small modular reactors, or SMRs, are drawing-board units and at a cost of $900 million to $1 billion each, could possibly be produced in mass in Missouri if Ameren Missouri and other electric companies, as well as stakeholders, have their way.

“The county is really hoping to get the new module plants,” says Jody Paschal, newly elected Callaway County assessor. “They would really increase our economic base and grow our communities even more. I think people enjoy working there, and I don’t think people feel unsafe having it in our community.”

In the beginning there was DOE

The story somewhat began in April 2012 when Westinghouse Electric, an international company with a presence in Missouri, first applied for Department of Energy federal funding to develop and manufacture SMRs, which are about a fifth the size of the large units currently in existence, in Callaway County. They didn’t receive the funds. A second application went out to DOE in April 2013. Again, denied. What’s next with Westinghouse and partner in production, Ameren Missouri, is anyone’s guess.

According to Ameren, the company is still looking at other options, such as pooled funding among existing Missouri energy companies and other interested stakeholders, Wood says.

According to Westinghouse spokesperson Sheila Holt, developing and manufacturing these SMRs are still part of their current and future energy goals for next-generation nuclear technology — somewhere in the United States. When pressed in an email about whether Missouri was part of their game plan, there was no response.

According to the State of Missouri, also a key player in the project, the state is ready when it comes time to assist if the project comes to fruition. “The state can provide numerous things in support of this type of venture,” Boone County Commissioner Dan Atwill says. “Tax credits, roads, encouraging businesses to participate, making it a friendly environment for the type of construction work that would be done with such a project.”

But why?

Everyone is affected by what leaders decide to do to replace existing infrastructure.

“Over the years, you really have to look at their average cost of energy, and we look at different options, and the future for nuclear power is attractive, especially as you look at an environment in the future where carbon emissions are regulated,” he says.

SMRs would provide a reliable and affordable energy source for decades, adds Todd E. Culley, CEO and general manager of Boone Electric Cooperative. Plus, the spent fuel could possibly be recycled and placed back into use, Culley says. But so far, he says the United States has not participated in recycling spent fuel, as other countries have.

In addition, another large nuclear plant is not the answer. Callaway was built during a time of urban sprawl, Wood says. It was a time when houses were being built, people were adding air conditioners to their homes and residents were purchasing a long list of new appliances. Therefore, large was needed: a large reactor, a large turbine, a large generator.

The economy has since slowed down, Wood says, with more energy-efficient homes and fewer homes being built. The SMRs are the perfect solution, he adds.

Is it safe?

According to Wood, Culley, Paschal and Atwill, these small nuclear units appear to be safe and, in fact, will help in the perceived need to reduce carbon emissions and stop climate change.

“If we are serious about reducing carbon emissions, we need to be serious about nuclear power,” Wood says. “It’s just as simple as that.”

Still, Atwill says there are some risks. “There’s always some room for an accident. One of the issues has been the possibility of earthquakes, but I think this one is on solid ground compared to others.

“(Still), I can say I’m 100 percent for the small modular reactor,” he continues. “From what I’ve learned in the process, I’m very confident it’s a very safe and efficient mechanism for the creation of electricity.”

Who benefits?

Of course the energy companies benefit by having a less-expensive, long-term mechanism for bringing a mostly carbon-free energy to the state as well as acting as world leaders in the development, manufacturing and sale of SMRs across the globe.

But the state and its people would also benefit. SMRs could bring another industry to the state. Although the economy is strong here — Missouri was a top-10 state for job growth in 2013, and Columbia’s unemployment rate is at 3.7 percent, according to a January 2014 report by Gov. Jay Nixon — Atwill says the state needs to continue to look for safe and beneficial economic stimulators, such as SMRs.

To build units for Missouri’s use would mean thousands of construction jobs and hundreds of permanent positions.

“But really, when we look at the transformational economic development opportunity this represents, it comes down to our ability to be a manufacturing center for the modules shipped to other states and countries,” Wood says. “That’s when you really get into the 10,000 to 20,000 jobs.”

Mike Brooks, president of Regional Economic Development Inc., says there are two specific ways to evaluate the impact. “One is the actual construction and development of SMR reactors at the Callaway facility; that is a significant economic impact,” he says. “The other opportunity here is having Missouri being the focal point for the actual assembly and research assembly of the SMRs that would be shipped all across the world. But by virtue of Westinghouse not being a recipient of the federal grant, we don’t know what effect it will have on this bigger picture of what SMRs might mean to Missouri.”

“If you look at the SMRs’ potential worldwide, in my mind there is no question [production of them] will become a significant economic development opportunity for one or several countries,” Wood says. “And the United States has an opportunity to be a leader in this if we step up and perform. Or we have the opportunity to let other countries lead in this area. I hope our country is not going to let the second option happen.”

But for Wood and others, they want Missouri, not another site in the United States, to be home to these SMRs and all that would mean to the state and its future. With funding from a variety of sources, the sharing of costs would make it more feasible for all involved. “To summarize, we are stepping back and looking at options,” Wood says.