MU J-School grad led a novel life

- About the author: Joshua Amelunke is a local historian and freelance journalist. He grew up in Columbia, Mo, and attended both Columbia College and the University of Missouri.

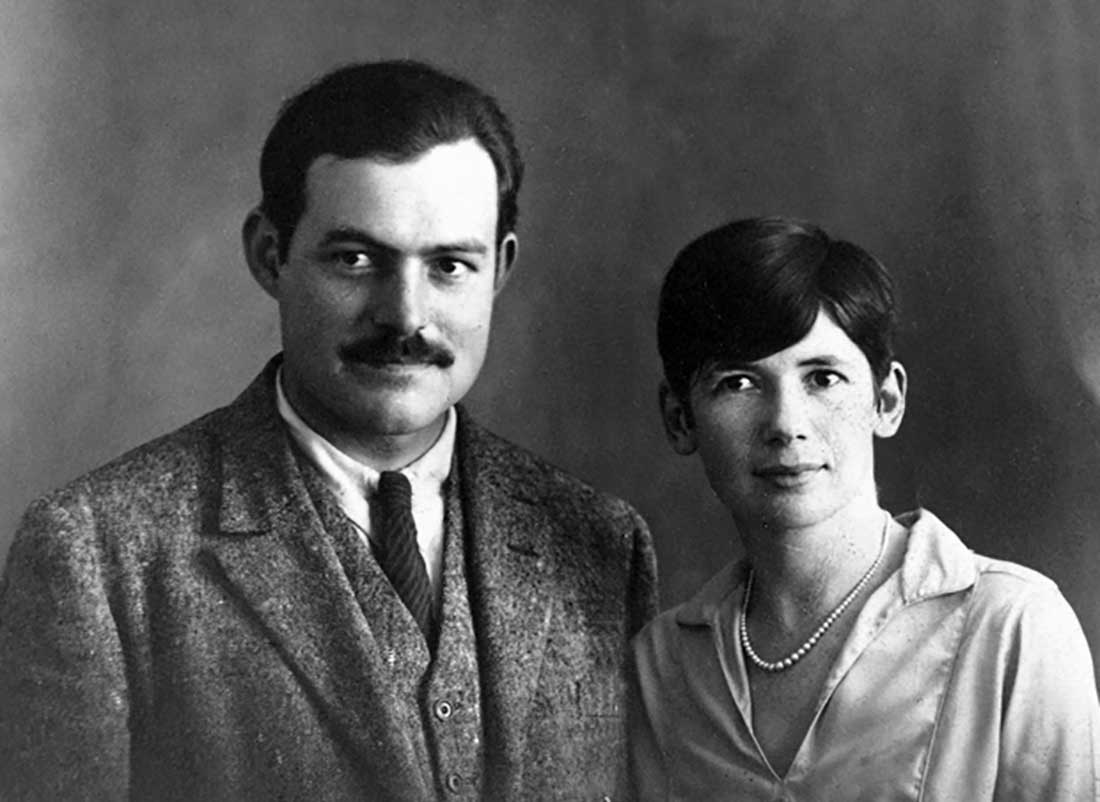

Pauline Pfeiffer was the woman behind Hemingway’s success

Most students passing through the University of Missouri’s historic Francis Quadrangle have no idea that Ernest Hemingway’s second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, attended Mizzou’s School of Journalism. Like students of today, she lounged in the quad with friends, excelled in her classes at Switzler Hall, and rushed to and from her school and home, in what is now the Historic East Campus Neighborhood.

Pauline Pfeiffer was a hard-working student looking to pursue a journalism career. Her time at the university, and career success, ultimately contributed to the achievements of her husband, Ernest Hemingway.

One hundred and five years ago this spring, Pauline graduated along with 28 other members of the Missouri J-School’s Class of 1918. Rarely given credit for anything more than being the second wife of Ernest Hemingway, her success as a journalist is well documented in the archives of Vogue. Pauline’s education and influence on Hemingway’s writing can be seen in his books, and letters written to his associates.

Education and university life

The Pfeiffer family moved from Iowa to St Louis in 1901. Pauline was enrolled into Visitation Academy, an all-girls Catholic school. In 1913, she graduated “a student of high merit and recipient of the English prize.” Years later, Visitation Academy’s alumni bulletin commented that her success with Vogue Magazine was not a surprise, and recalled she was always on top when creating a personal style with the school’s uniforms.

Shortly after graduation from Visitation Academy, Pauline’s father, Paul, sold his shares in Pfeiffer Pharmaceuticals — the family business — to his brothers. The family relocated to Piggott, Ark., with her two brothers Max and Karl, sister Virginia, and mother, Mary. She moved with the family to help them settle, which proved fortunate as she was also able to care for her brother after a burn left her mother hospitalized.

Once Mary was well, Pauline was free to move on. Less than 300 miles away in Columbia was the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the first of its kind in the United States. Founded by Walter Williams at the urging of Joseph Pulitzer and the Missouri Press Association, the school opened in 1908.

A degree from the prestigious journalism school would provide a perfect opportunity for Pauline to pursue her passion for writing.

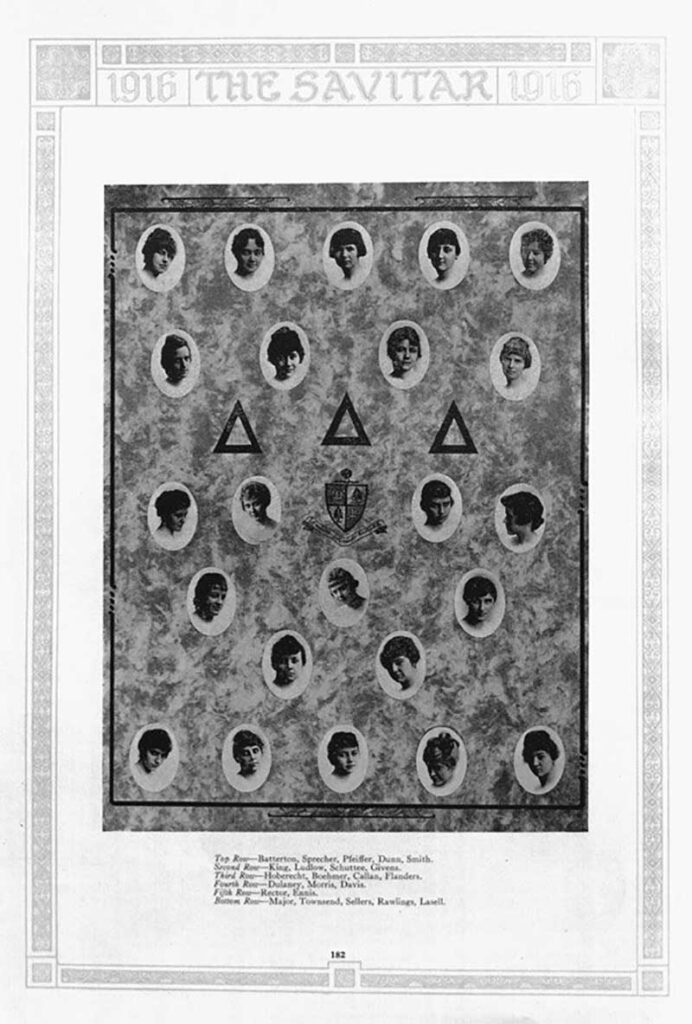

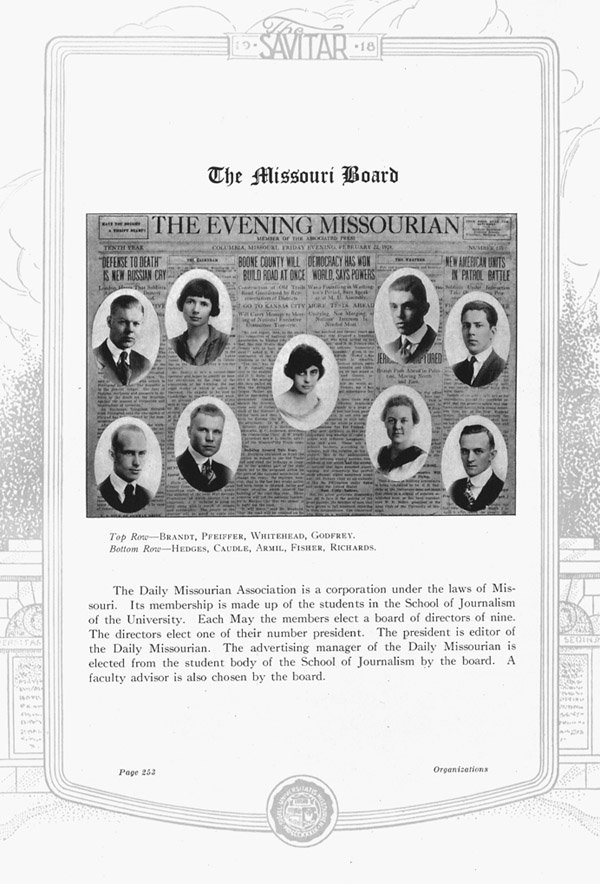

In 1915, Pauline moved to Columbia and started her education. An active member of the student body, she served on the Daily Missourian’s board and was a member of the Tri Delta sorority. Her work on the paper during war time included headlines from several conflicts during the First World War. (Hemmingway would later use the same settings in his book A Farewell to Arms.) Pauline’s classmates at the time recall her focusing on school and not having much of a social life. Overloaded schedules, and summer attendance allowed Pauline to graduate from the University in just three years.

She received her degree on June 5, 1918, as one of 13 women in the MU J-School’s graduating class. The journalism school’s reputation almost guaranteed her employment. An article in The Evening Missourian on May 21, 1918, posted all 29 journalism graduates’ plans after graduation. Pauline’s post read, “Miss Pauline Pfeiffer came to the university in the fall of 1915 and will receive her degree in June. She wishes to do copy-desk work on a city paper this fall. Her home is in Piggott, Ark.”

Journalism: Europe and Vogue

After graduation, Pauline found employment with the Cleveland Press working at the night desk. Tragically, her employment in Cleveland was cut short when her younger brother died suddenly during the influenza outbreak of 1918. Max’s burial was rushed due to the fear of contagion. Pauline, her brother Karl, and sister were unable to attend.

Pauline quickly returned home to Piggott to be with her family and lost her job due to her time away. Her boss explained that he could not hold the position open but would find her a staff position when she was ready to return to work. She stayed in Piggott through the holidays.

In early 1919, Pauline moved to New York, rather than return to Cleveland. She found employment working for the New York Daily Telegraph, then later with a number of other publications including Vanity Fair and Vogue.

After her first trip to Europe in 1922, she returned to her alma mater to visit her sister who was attending the university. The Columbia Evening Missourian reported on its alumni’s visit and success with front page coverage on Monday Oct. 16, 1922, “MISS PFEIFFER VISITS HERE, Graduate of University Returns From European Tour.” Like a proud mother speaking of her children’s accomplishments, the paper listed several of Pauline’s achievements since graduation, including writing articles for the News Enterprise Association of New York, interviewing motion-picture stars for Selnick, working for the American Relief Administration under Hoover, and writing for Vogue.

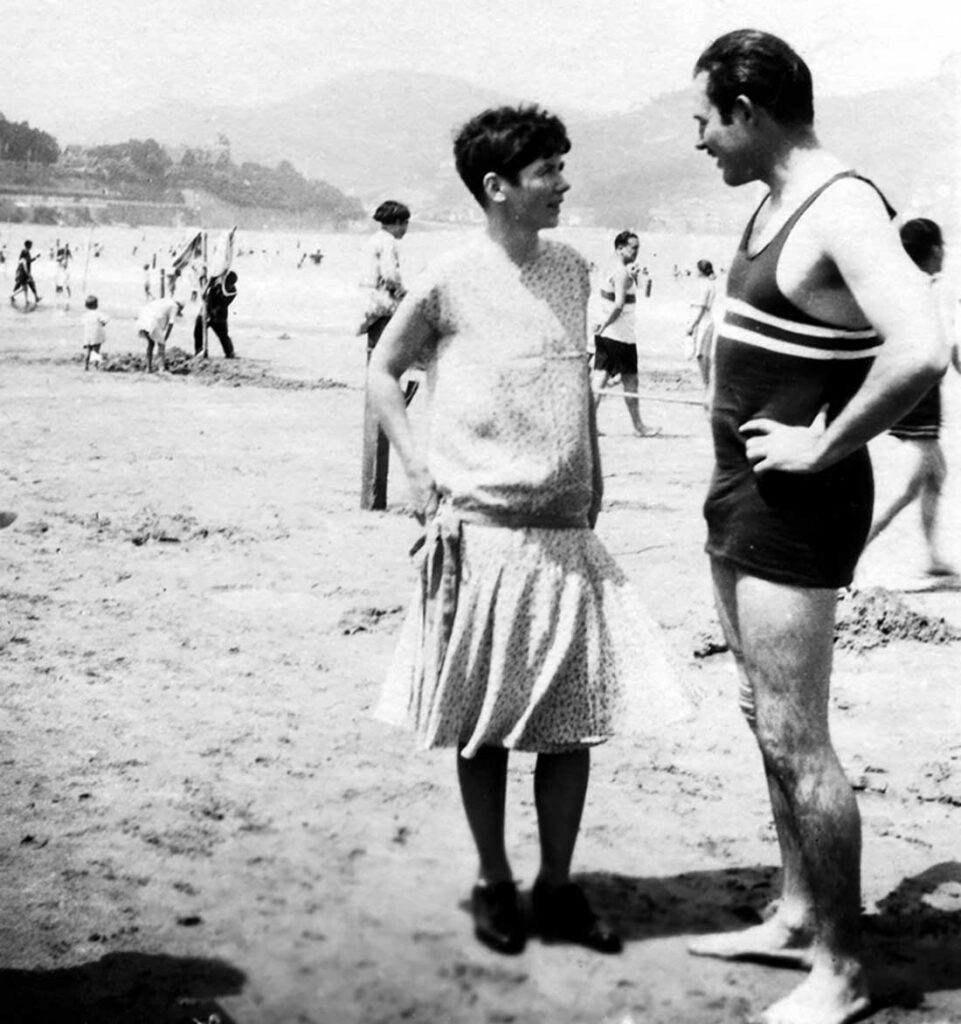

Pauline’s good journalism and experienced eye for fashion earned the attention of Vogue’s Paris bureau, where she was temporally transferred in 1924. Vogue writer Lesley M. M. Blume described Pauline’s professional life at the time as “basically a feminine version of Hemingway’s” and “often writing in the first person and revealing herself to be smart, witty, stylish but self-deprecating, and surprisingly likable.”

A mutual friend introduced Pauline to Hadley Hemingway during this time. Hadley was also from St. Louis. Her husband, Ernest, was a struggling writer trying to live a high society life on Hadley’s modest trust fund.

Pauline’s relationship with the couple and their young son changed as she found less in common with Hadley and more in common with Ernest, both professionally and romantically. She could offer professional advice on the young author’s manuscripts and her increasingly large trust fund and family money could also provide him with the lifestyle that he coveted. Her trust fund at the time was near $3600 per year (in 1927 dollars).

The trust, along with help from her family, Ernest’s payments from stories, and the gifts they would receive throughout the years provided a comfortable income.

A silent editor

Before the two were married, Pauline’s encouragement, education, and experience had helped launch the struggling author’s first books. Hemingway’s novel, The Torrents of the Spring, was almost not published. Hadley did not like the book, but she later confessed that if not for Pauline’s encouragement, Ernest would have never submitted it.

In 1926, Hadley became fed up with the affair between her husband and Pauline. She requested that the two of them separate for 100 days to confirm it was more than a dalliance, and Pauline returned to Arkansas during the separation.

While Hemingway revised the manuscript of The Sun Also Rises, he sent Pauline letters professing his love and seeking feedback on the edits.

During their time apart, Vogue offered Pauline a job in the New York office. Perhaps afraid of losing Pauline to Vogue, he asked her to “hurry” back to him in Paris before their 100 days separation was through. Pauline hopped on a ship and, heading for Paris, the job was never mentioned again.

Giving up her career cemented the idea that she would soon become Mrs. Hemingway, a silent partner in his literary success.

Ernest Hemingway’s greatest literary years were those he shared with Pauline. Upon being married into the Pfeiffer family, the struggling writer had gone from a small apartment where he had lived with his ex-wife and their son, to three apartments paid for by Pauline’s family. Not only did she provide financial stability, but she also brought skills and a network acquired during her impressive journalism career.

Not surprisingly, Hemingway’s opportunities were increasing daily. The New Yorker published the short story “How I broke John Wilkes Booth” and was asking for more. Vanity Fair, who had turned Hemingway down in the past, was a publication now asking for his work.

Pauline’s professional opinion was well respected by her husband’s editor, Max Perkins. The two communicated throughout Ernest’s career. In an early letter written from Perkins to F. Scott Fitzgerald, he expressed a reluctance to publish one of Hemingway’s short stories from the collection Men without Women. He then goes on to explain, “On the other hand, Mrs. Hemingway told me that the story could be made acceptable even for conservatives by striking out a few psychological details.”

Back to the states

As a result of his divorce from Hadley and other betrayals among friends, Hemingway’s Paris relationships were dying off by the day. Pauline’s pregnancy expedited their return to the U.S. Pauline’s wealthy Uncle Gus ordered the couple a new Ford Model A Coupe and shipped it to Cuba for their arrival. The couple then made their way to Key West where Ernest discovered his passion for deep sea fishing. Mr. Pfeiffer visited the couple and after seeing how uncomfortable his daughter’s pregnancy was, he immediately sent her back to Piggott by train. Ernest and Paul drove back to Piggott to meet her.

While in Piggott, Pauline’s family turned an unused barn into a writing studio for their son-in-law. A large portion of A Farewell to Arms was written in the Piggott studio. The story, based in Italy during World War One and around Hemingway’s time in the war, also borrows off Pauline’s Uncle Washington Pfeiffer’s war time experiences.

Washington was in Italy visiting family during the First World War and was forced to flee to Switzerland after being trapped behind enemy lines, much like Fredric Henry at the end of the novel. Novel character Catherine’s difficult birth and death in the novel was inspired by Pauline’s caesarean section birth of their son, Patrick, and her difficult recovery.

In December of 1928, Ernest’s father died by suicide, making it difficult to concentrate on completing A Farewell to Arms. Ernest’s sister, Sunny, who was in Key West at the time, worked with Pauline to edit and type the manuscript. In a letter to Max Perkins in January of 1929, Ernest informed his editor, “My sister and Pauline are both typing on the book today and I will have 29 chapters in type by night.”

In 1931, with nearly eight million Americans out of work, Pauline and Ernest were set, the couple’s bills were paid, their Key West home was paid for — thanks to Uncle Gus — royalty payments were coming in, and they had Pauline’s trust fund. This allowed Hemingway to pursue his ongoing interest in bullfighting, as he wanted to “write the book” on the sport.

Through his overseas business ventures, Uncle Gus had amassed several contacts. At the request of his nephew-in-law, Gus sent a message to his plant manager in Spain, telling him to round up everything that was ever written on bullfighting, send it to Ernest, and send the bill to Gus. The book named Death in the Afternoon was published in 1932.

Africa

Uncle Gus set aside $25,000 in 1933 to fund an African safari for his niece, her husband, and a friend. The safari would open Ernest’s eyes to more of his inspirations, big game hunting, and the African wilderness. Pauline kept a detailed journal of the trip that showcases her writing talents and outlines successful stories written by Hemingway after the trip.

The Green Hills of Africa loosely describes Pauline and Ernest’s hunting adventures in Eastern Africa. Her journal, which is now published in the new edition of Green Hills of Africa, reveals that it was not entirely factual. Her husband rearranged some chronology and minimized his bout with dysentery.

Two successful short stories were inspired by the trip. In The Snows of Kilimanjaro, about a writer in Africa dying of gangrene, Ernest artistically alters his bout with dysentery and severe diarrhea, having to be airlifted from the bush. Pauline’s journal also describes the near tragedy when Ernest’s loaded rifle fell off a car and fired. The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber was inspired by this event; however, in true Hemingway form, it is the wife’s mistake that kills the protagonist of the story rather than his own.

Hemmingway away in Spain

Hemingway’s lust for adventure, and a new female inspiration, Martha Gelhorn, took him to Spain to report on the Spanish Civil War. Pauline remained in Key West to take care of their children; Ernest continued to write overseas but his dependence on Pauline persisted. The 1938 short story The Night Before Battle was written during Ernest’s time away. In some correspondence to Esquire editor Arnold Gingrich, in reference to his poorly edited manuscript, Ernest explained, “Pauline, whose word I take on grammar is not here.”

The Fifth Column was released while Ernest was still away in Spain. Max Perkins sent Pauline the book a few weeks earlier for approval. She did her best to promote the book in her husband’s absence and was angry when she found out that Scribner, the book’s publisher, did not display any copies of the book in its windows.

Adding to her displeasure with the situation was her husband’s absence to tend to the issue. She immediately contacted him, poetically hinting that his literary and marital priorities were out of order, “Perhaps my dear fellow you should be shifting from your mistress—shall we call her War— to your master.” Ernest quickly contacted Max Perkins to inquire about and remedy the problem.

Ending the silent partnership

For Whom the Bell Tolls was published and released Oct. 21, 1940, shortly before Pauline and Ernest’s divorce on Nov. 4. In a letter to Max Perkins on May 18,1940, Ernest wrote, “Pauline hates me so much now she would not read it [For Whom the Bell Tolls] and that’s a damn shame because she has the best judgement of them all.”

Pauline kept the house in Key West and ran a small decorating shop down the road. She offered her editing skills and contacts to young author Jack Latimer. Knowing how Ernest valued Pauline’s editing skills, he gratefully accepted her offer and his work was published. This was perhaps the last time Pauline would use her skills as an editor.

Pauline died in 1951 at her sister’s home in Hollywood, Calif. For years, Pauline’s image would sadly reflect Hemingway’s vilifying portrayal of her destroying his first marriage in A Moveable Feast published 1964 after his own death. But Pauline was the great woman behind Ernest Hemingway and his great writing.

Although he never publicly gave Pauline credit, years later he was still bragging to his fourth wife, Mary, about Pauline’s editorial skills. Hemingway died by suicide at his house in Ketchum, Idaho, on July 2, 1961, after years of suffering from anxiety and depression.

Bibliography

- Baker, Carlos Hemingway: A Life Story, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969.

- Blume, Lesley M.M. Everybody behaves badly: the true story behind Hemingway’s masterpiece The sun also rises. Boston, MA: Eamon Dolan/Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

- Blume, Lesley M.M. “The Vindication of Pauline Hemingway, Ernest’s Second (and Most Vilified) Wife,” 2016, accessed 27 February 2018; available from https://www.vogue.com/article/pauline-hemingway-forgotten-wife; Internet.

- Dearborn, Mary V., Ernest Hemingway: A Biography, New York: Knopf, 2017.

- Farrar, Ronald T., A Creed for My Profession: Walter Williams, Journalist to the World, Columbia Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1998.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott, and Maxwell E. Perkins. Dear Scott/Dear Max; the Fitzgerald-Perkins correspondence. New York: Scribner, 1971.

- Hawkins, Ruth A. Unbelievable Happiness and Final Sorrow: The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Marriage. University of Arkansas Press, 2012.

- Hemingway, Ernest, and Carlos Baker. Ernest Hemingway, selected letters, 1917-1961. New York: Scribner, 2003.

- Hemingway, Ernest, Patrick Hemingway, Seán A. Hemingway, and Edward Shenton. Green hills of Africa. New York: Scribner, 2015.

- “Journalism Officers Elected, “The Evening Missourian, Columbia, MO, Dec 15, 1916.

- Kert, Bernice. The Hemingway women. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

- Long, Adam, Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies, “Introduction: The View from the Hill” Volume 45, Number 2.

- “Miss Pfeiffer Visits Here: Graduate from University Returns from European Tour,” The Columbia Evening Missourian, Columbia, MO, Oct. 16, 1922.

- Reynolds, Michael S. Hemingway: The Homecoming. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

- Reynolds, Michael S. Hemingway: The 1930s. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1998.

- “Society,” The Evening Missourian, Columbia, MO, Oct. 24,1915.

- “The University Graduates of 1918,” The Evening Missourian, June 5, 1918.

- “16 Men, 13 Women, to get B.J. Degree: Members of the Class will be Widely Scattered after Commencement,” The Evening Missourian, Columbia, MO, May 21, 1918.