An Empty Lot in the District Shows Promise

After a lengthy cleanup process and years of vacancy, will the City of Columbia and Ameren reach an agreement on a North Village Arts property?

The North Village Arts District in downtown Columbia has a lot to offer.

Styled as a “bohemian paradise,” the area is filled with hip shops, cafés, and art galleries where more than 150 artists share their work. In the center of this paradise, however, is a piece of property that nears dereliction.

Surrounded by a chain-link fence and signs that read “no parking any time,” the property at 210 Orr St. has been described as, at best, an “eyesore” in an otherwise thriving part of the city.

As barren as it looks now, the site has had a rather long and complicated history.

In the late 1800s and early 20th century, the property was used as a manufactured gas plant where Columbia Gas Works produced gas from coal or oil for lighting, cooking, and heating. The property’s pavement, now covered in weeds popping up through the cracks, was once the site of boilers and gasholders.

Several years and name changes later, Union Electric Company — now owned by Ameren — closed down gas production in 1932. Up until a decade or so ago, the property was an Ameren maintenance site where the company kept its service trucks overnight.

Although still owned by Ameren, it is now all but abandoned.

Over the years, there have been numerous calls from city residents and city officials to purchase the property, with many members of the North Village Arts District citing the area as a perfect place for a greenspace.

The city has a “right of refusal” agreement with Ameren to have the first opportunity to purchase the property if it ever goes up for sale. However, even after two subsequent cleanups of the area — in 1994 and 2013 — there are still concerns about what possible contaminants remain from the former gas plant.

Clean It Up

Beginning in the mid-’90s and into the early 2000s, Ameren began to investigate possible soil contamination on the site left over from the gas plant. In 1994, the company conducted a cleanup of impacted soil on parts of the property. In 2006, Ameren began plans to move its service facility from the property and apply for a brownfields voluntary cleanup with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. That cleanup began in 2013.

Chris Cady, an environmental scientist with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, says a brownfields cleanup is a way for people to take care of a contamination problem and often facilitates the sale or redevelopment of a property. The natural resources department oversees the cleanup process, and once it’s completed, a “clean letter” is issued stating that a property meets all requirements.

“The important term is ‘voluntary,’” Cady says. “It’s not an enforcement program. People bring properties to us that they want to clean up, and what they get on the back end is a letter from the state saying you’ve cleaned up the site to our standards and it’s suitable for future intended use.”

Cady says most states have these voluntary cleanup programs because it helps keep properties redeveloped instead of sitting unused due to environmental concerns — most people don’t want to buy a property that is considered contaminated.

And that’s where the status of the Ameren property gets interesting.

During the cleanup of the site, Ameren removed over 30,000 tons of contaminated soil and debris found anywhere from 14 to 21 feet below the surface. Cady estimates that the cost of the cleanup was between $4 and $5 million.

The brownfields cleanup of the site was officially completed in 2018, and on October 11, 2018, Ameren received their official “clean letter” from the department. However, Ameren’s completion letter also included an “environmental covenant” agreement with the natural resources department with several restrictions on the use of the property.

Although the site’s cleanup was completed to the department’s standards, there is still some contamination left underneath the property that restricts the property’s use. After the completion of the cleanup, the department listed contaminants of concern that still remained on the site, including several carcinogens like benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Although these contaminants are deep enough below the soil to not be an immediate concern, the natural resources department covenant states that: “The property shall not be used for residential purposes; soil on the property shall only be disturbed with consent by the department; construction of any new buildings is allowed only with written approval by the department, and there should be no drilling or use of groundwater on the property.”

Cady says that, with these rules in place, the property is considered safe and, if an entity like the city was to purchase it, no further certifications would be required.

“It meets our standards with certain restrictions in place,” he says. “As long as these limitations are followed, then it’s safe. The certification runs with the land, it doesn’t matter who owns it as long as those requirements are upheld. The new owner is subject to those requirements unless someone does more investigations and finds more contaminants or someone does additional cleanup.”

In terms of what the property could be used for, Cady says most of the contamination found is 10 to 20 feet deep, so development on the surface would not be affected by the restrictions. Especially if the development was — like many residents have called for — bought and turned into a park or green space.

“I think (a park) would work, yeah,” he says. “A park is generally a surface type of use and the issues that are remaining at the property are generally pretty deep.”

A Green Space

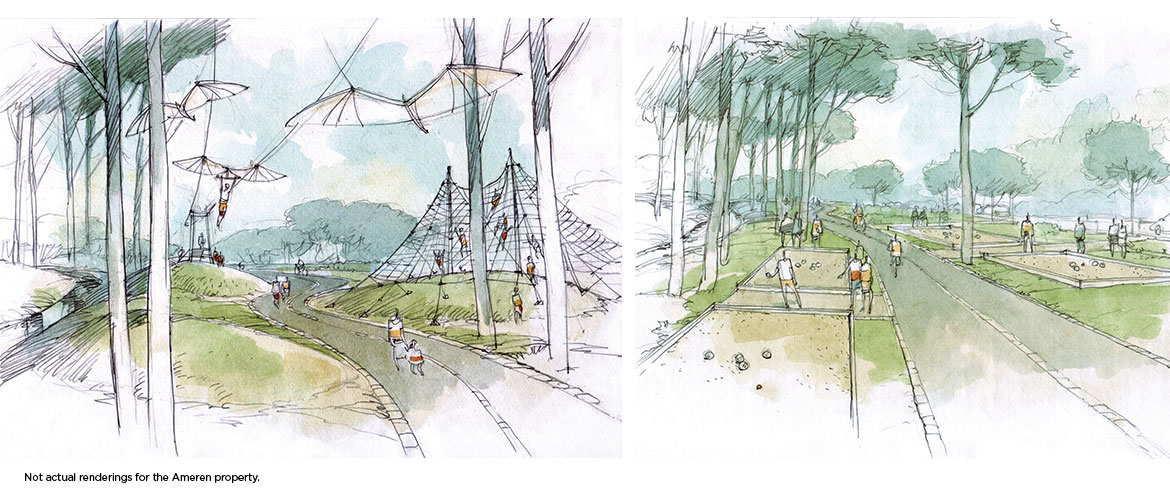

The concept of turning the lot into a green space or park has been on the minds of city officials and residents since 2010, when city council approved the idea in the H3 Charrette Plan. In 2013, when Ameren first began to clean up the area, city council also adopted its Columbia Imagined city planning document with possible ideas for the site.

With the site now approved by the natural resources department with an environmental covenant, many residents and groups in the area, like the North Village Arts District board and the Downtown Leadership Council, have asked the city to purchase the property. Both groups have written letters to members of city council with ideas of what to do with the property.

In a letter from the North Village Arts District board to the city council, the board expressed their disappointment with the restrictions on the property by the department of natural resources and stated, “The best course of action would be for the city and our organization to work with Ameren to acquire the currently restricted two-acre plot at a great discount, relieving Ameren of all liability, contingent on the city securing a brownfields environmental cleanup grant from the EPA with the help of our state and local officials.”

The letter from the Downtown Leadership Council echoed the sentiment that the property should be purchased in hopes of further cleanup and less restrictions.

For realty owners in the area, like John Ott, and business owners, like Van Hawxby, who owns DogMaster Distillery across the street, a park or greenspace would only further improve an already vibrant part of the city.

“The arts district continues to grow in popularity, and every six months you go, ‘Wow, there’s something new here, there’s a new business here, there’s more artists here, there’s more activities and events, and there’s more visitors,’” Ott says. “It’s really pretty exciting to see how it’s growing, and so to be able to add a greenspace like that in the center of the arts district — it would just be a real asset. You could have musical events. You could have many arts festivals , just events and activities that could lend itself to the arts district’s quality of life.”

Will they sell? Will they buy?

However, as residents call on the city to act, city officials say the ball is in Ameren’s court. Councilman Michael Trapp, who once was one of the main advocates of purchasing the property, says he’s become less optimistic about its potential use to the city.

“We certainly would be in a place where we would spend a considerable amount of money for a property that we may or may not be able to use in any way that kind of advances city aims,” Trapp says. “It would be an uncertain, expensive process to try to get it cleaned up where it could be used beyond a surface parking lot.”

When the city was imagining plans for the property, Trapp says he had several ideas, like a Turkish market, commercial mixed-use space, or an open greenspace.

“It’s a neat area, and you can do a lot of things on the property if we had the environmental clearance, but as the years have gone by, it seems increasingly unlikely that there’s going to be any level of environmental clearance for any projects that the city might be interested in,” he says.

Interim City Manager John Glascock says that although Ameren has not officially approached the city about purchasing the property, there will be ongoing discussions about what the company’s next step will be.

“Any greenspace is good in a downtown area,” he says. “It could be a sculpture park. It could be just a regular walk-through park. It just depends on what council sees it as. . . . You’re going to have to have a lot of public input. I would suspect the residents might see it differently from the arts district, so you always have to have that discussion.”

Before any decisions can be made, they first have to agree on a price.

“We’re on the buying end of it and they’re on the selling end of it, so they’re in control. We’re not,” Glascock says. “It’s really up to them.”

According to Boone County’s online real estate information, Ameren’s property is currently appraised at $651,237.