What does Columbia’s Student Housing Look Like Now?

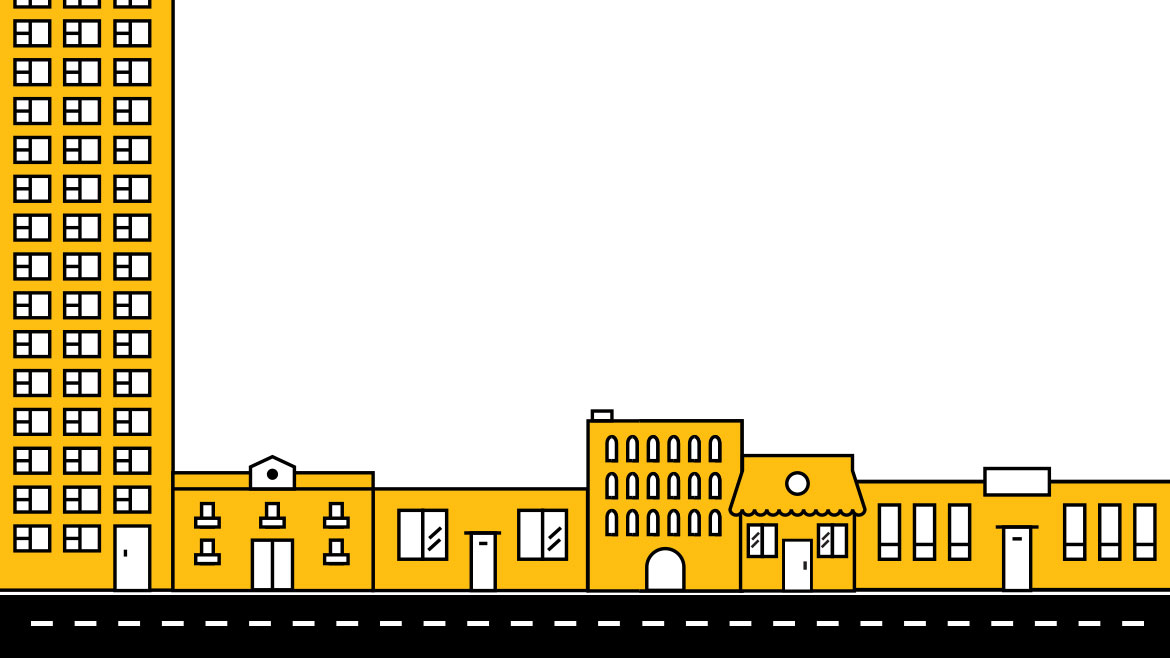

At 128 feet, Rise on 9th, the newest in a slew of downtown luxury student apartments, is the sixth tallest building in Columbia, according to Emporis Research. The building’s 10th floor penthouse lounge offers an aerial view of MU’s campus and downtown. The paneled glass windows provide students an almost complete panorama of Missouri’s fourth most-populous city. Crowded alongside Columbia’s easy-to-spot landmarks like the white dome of Jesse Hall or the bright red sign atop the 91-year-old Tiger Hotel is a massive tower of red, gray, and beige.

The current skyline of Columbia is drastically different than it was just under a decade ago. Swarms of new student housing developments have sprung up all over town and, recently, the buildings have reshaped the city’s downtown landscape.

In the mid-2000s, enrollment at MU was increasing. Developers saw the swelling demand for student housing, and pretty soon apartments began to line the streets along Highway 63 outside campus. Enrollment reached its peak in 2015. With 35,488 students enrolled — almost 30 percent of Columbia’s population — and plans to keep that number increasing, there was plenty of reason to build off-campus housing. As more developers moved into the area in response to the increasing demand of students, it created a student housing bubble.

Between 2015 and 2017, however, enrollment plummeted around 12 percent, according to MU data. With the decrease in student numbers and the subsequent temporary closure of seven on-campus residential halls, the student housing market has struggled to adapt to the shifts in demand.

Currently, there are no pending housing developments downtown. Those projects that went up during the enrollment boom, however, are left to compete in a crowded market with fewer customers.

The Bubble Burst

The possible decline in MU enrollment and its effect on housing has long been speculated. In 2014, the Odle family, the Columbia-based developers of the Brookside student housing apartments, published a report that condemned the influx of downtown development and predicted “a bleak picture for increasing student housing demand.”

After the report was released, however, the Odle family continued to build, demolishing Shakespeare’s Pizza’s original location and Bengals Bar and Grill to develop new housing.

In the report, the Odles urged developers to wait for older properties to become obsolete before considering any new projects and to prepare to purchase “distressed” buildings. The report predicted these obsolete and distressed properties to appear over the course of four to eight years.

In the years after the release of the report, the demand for student housing began to drop as MU’s enrollment plunged, but developers kept building.

Columbia real estate agent John John said the Columbia student housing bubble burst during the 2015 protests at MU.

Three years ago, a wave of race-related incidents and protests swept through the campus, leading to the resignation of UM System President Tim Wolfe and MU Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin.

“What happened happened, and that caused students to not want to come to MU,” John says. “Until that turns back around, we’ve got more housing by 5,000 beds than we need.”

However, there has been no comprehensive explanation for why enrollment at MU did drop and, in 2018, freshman applications are actually up by about 17 percent over last year, according to the UM System Board of Curators.

John disagrees with the idea that the decrease in student enrollment and its subsequent effect on housing demand could have been predicted. Before the 2015 protests, officials at MU predicted a yearly influx of incoming students with a goal of reaching 40,000 students by 2020, and developers built accordingly.

“The fact is, if the university kept on track, we did not overbuild,” he says.

However, John said, there are peaks and valleys in all forms of real estate, and supply and demand rarely reach equilibrium.

“You get into a situation where there’s a huge demand and everyone starts to build and they build until they’ve completed the demand,” he said. “At some point, you overbuild a little bit and then there’s a valley until that overbuild capacity is used up and it starts up. Those waves go in every real estate market there is.”

Enrollment at MU first began to swell in the early 2000s. JPI, a Dallas-based apartment developer, was one of the first companies to capitalize on the demand for student housing in Columbia by implementing multi-room floor plans. Along Highway 63, the developer erected Jefferson Commons, now owned by Education Realty Trust and renamed The Reserve.

As MU’s student population continued to rise, developers followed in JPI’s footsteps and began marketing to students. At the same time, on-campus housing development at MU lagged behind; the school “only added a total of 3,000 beds from 2003 to now,” John says.

As MU Residential Life failed to compete with the luxury amenities and increased independence provided by off-campus housing, developers began inching closer to downtown and campus. Apartments like District Flats, The Lofts at 308 Ninth, Rise on 9th, Todd, UCentre, and three Brookside locations have sprung up across downtown boasting resort-style features and prime location.

However, as the customer base has failed to grow as expected, the influx of student housing has forced a rather ruthless bidding war between complexes.

“What’s happening now is the downtown buildings are able to suck all the tenants out of the ones that are scattered along the edge of campus,” John says. “The further out they are, the higher the vacancy rate.”

Moore and Shyrock, a real estate appraisal company in Columbia, keeps track of these vacancy rates, or the percentage of vacant or unoccupied units in a rental property at a given time.

The company’s most recent report, released in fall 2017, stated that, while downtown student housing complexes are less than six percent vacant, the apartments outside downtown were more than 20 percent vacant. With the increase in competition, many apartment complexes have been forced to adapt their marketing strategies.

Bidding War

To cope with the decrease in student demand, complexes have implemented new ways of attracting potential tenants. Apartment staff workers set up tables at Speakers Circle on MU’s campus and offer students free food and gift cards for signing leases. Companies offer discounted rates to tenants who choose to re-sign another year, and some companies have even taken to placing advertisements and flyers in the parking garages of their competitors. Some complexes allow tenants to postpone their rent payments until student loans are dispersed.

Most of the housing complexes in Columbia submit their current leasing and occupancy rates to a market survey to compare the performance of each competing company. The UCentre, located on Turner Avenue near Greektown, offers two-bedroom floor plans for $999 a month per occupant and four-bedroom plans ranging from $809 to $839 a month. Shaylan Thompson, the leasing manager for UCentre, says that due to the saturation of downtown housing, students can essentially wait until the last minute to sign a lease, so his company focused heavily on customer service and competitive rates to remain occupied. The complex is 100 percent leased for next year.

“We worked our butts off,” he says. “This past fall, it was rough with marketing and constantly explaining things to people, being overly thorough with things, tour after tour after tour, football games, basketball games — it took a lot. I think what separates us is our customer service.”

Thompson agreed with John’s assessment about student housing and said that students are becoming increasingly more attracted to living downtown and near campus, as opposed to some of the complexes on the outskirts of town.

Although the UCentre plans to be 100 percent occupied for next year, other complexes have had issues attracting tenants. According to the market survey, the next closest competition is only 57 percent leased for next year.

“As far as I know, no one’s really even close,” Matt Olsen, a community assistant for UCentre, says. “I don’t think anyone is much over 50 percent as far as being leased next year.”

Over off Grindestone Parkway, The Den, which offers such amenities as a pool, a sand volleyball court, and a 24-hour gym and game room, leasing for next year is below 50 percent.

“We pretty much up our marketing,” Shiv Patel, a leasing consultant for The Den said. “We pretty much go on campus and market every day. We’ve learned that students love free food, so we’ll always go and market with food just so we can get more people to our tables.”

Just like the UCentre, The Den offers two-bedroom options with pricing ranging from $675 to $705 per occupant per month and four-bedroom options with pricing between $499 to $529 a month.

Despite the company’s current low leasing percentage, Patel said he has seen a steady increase in signings as the end of the school year draws near.

Amy Karpowicz, the marketing coordinator for Todd apartments, said she could not disclose the company’s current percentage of signed leases. Todd, which sits at the corner of Fifth Street and Conley Avenue next to the UCentre, offers two-bedroom floor plans starting at $979 a month, a three-bedroom option for $885 a month, and four-bedroom plans starting at $749 a month.

The Future

Given the city’s past attempts to halt downtown housing development and the demand for student housing on the decline, the future of the market remains unclear.

The students that were a part of the 2015 enrollment peak will soon be graduating and, for at least the next four years, the overall net enrollment at MU will remain below that number.

“There’s little to no possibility of anybody wanting to build more housing in Columbia at this point or at least until the university is back up to where they were before,” John says. “It’s easily five years or maybe more than that before anybody comes back and builds student housing anywhere, not just downtown.”

While the debate over downtown development persists, student housing complexes will have to continue to compete with each other and some may have to choose between lowering their prices to attract tenants or going vacant.