Retire-what?

Most people look forward to a time when they’ll no longer be working. But for three Columbia area residents who are past retirement age, their professions are part of who they are. Although their views all vary about what retirement is, Lenard Politte, Halcyone Perlman, and John Whiteside all see their work as something bigger than a job — and retiring isn’t on the table (at least not right now).

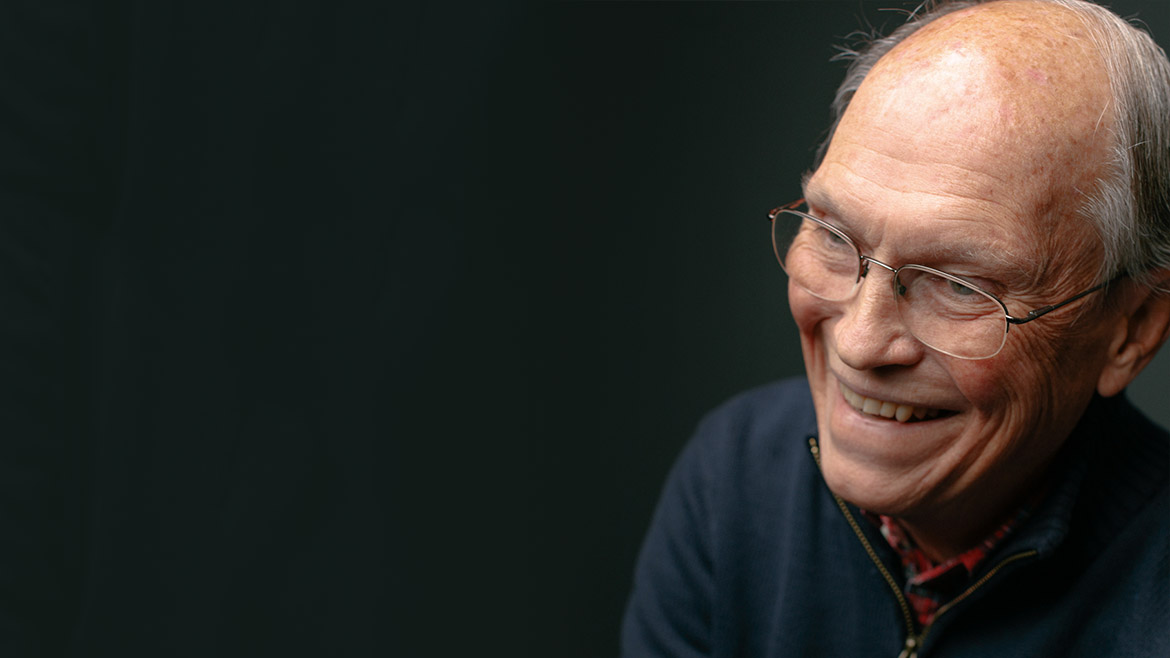

Lenard Politte

For Dr. Lenard Politte, 83, cardiologist and professor of clinical medicine at the MU School of Medicine, retirement is not a goal. “I will never retire from my profession,” he says. “You don’t retire from a job. You retire to do something else. The question should be, ‘What are you retiring to?’”

In 1969, Dr. Politte pushed for and helped develop the first heart program in Mid-Missouri. This included the cardiac catherization lab and the cardiology and open-heart surgery programs at Boone Hospital Center.

“Medicine has come a long way from when I first started practicing,” he says. “It’s accelerated greatly, and what’s made it accelerate is how we handle information. The computer chip has revolutionized everything because we can now gather and share knowledge from many different sources.”

Politte says he had hard-working parents, who only had fourth grade educations. They wanted better education for their children. After graduating college with a bachelor’s degree in zoology and a minor in psychology, he married and then went to work at McDonald Aircraft in St. Louis.

He wanted to further his education and had an interest in biology. With the encouragement of others, he decided to go to medical school. “I thought only the smart or the rich went to medical school, and I was neither,” he says. “But I wanted to do something to help others, so I enrolled and got into the University of Missouri.”

Before he graduated, his father died of heart disease. This helped set the course for him to go into internal medicine, specifically cardiology, after spending three years in pathology. He was trained as one of three fellows and stayed on as junior faculty in cardiology at the MU School of Medicine.

After a stint in the Army as a medical officer during the Vietnam War, he returned to his family in Columbia, where he went into private practice. From there, he helped develop the open-heart surgery program at Boone Hospital.

Politte is fascinated by the human body and helping others figure out what can be done to help a specific patient. “It’s always a challenge to figure out what is wrong and what can be done to correct it,” he says. “Every patient is different and each is a challenge. Each time we hope we can find a solution.”

After 30 years, he retired from private practice and began teaching cardiology fellows at the School of Medicine. He’s been doing that for 17 years.

Politte enjoys working with young doctors and helping them learn how to carry on as trained physicians. “I try to encourage them to perpetuate the profession as well,” he says. “I tell them, ‘You want to be remembered not for who you are but for what you do for others.’ I try to instill that in them so they can leave something to others as well.”

As much as he loves his profession, he loves his wife, children, and grandchildren more. He sees the real highlight of his job is helping people improve their quality of life — the same thing he set out to do when he enrolled in medical school.

He still readily gives out health advice (“Keep good health habits. Don’t smoke. Keep your blood pressure and cholesterol down. Stay active.”), and he’s optimistic about finding cures for all kinds of diseases, including what he calls the emperor of all maladies — cancer. He advises, “Keep your eyes on monoclonal antibodies for the answers.”

With so much work to be done, how could he step away?

Halcyone Ewalt Perlman

Halcyone Ewalt Perlman, 82, has taught ballet for nearly 60 years in the school her parents founded in 1933. She took over the school and renamed it the Halcyone Ewalt Perlman School of Ballet when her mother died in 1967.

Today, the school has been renamed the Perlman-Stoy School of Ballet. (Nancy Stoy is the co-teacher and director.) Perlman — again, age 82 — still teaches two classes and is involved in choreography.

The first studio, in the upper story of the southwest corner of Ninth and Locust in downtown Columbia, was also the family’s home. Even though she was raised in a studio, Perlman didn’t become interested in ballet until she was 14 and attended a performance of Margot Fonteyn, an English ballerina.

“I was amazed to see how much was involved in the performance,” Perlman says. “I was really moved by her musicality — that’s ability to interpret the total body of the piece through mood, rhythm, tempo, and movement. [Before that,] I had been interested in being a veterinarian, entomologist or in training and breeding horses.”

Once Perlman was captured by the beauty of the movement of ballet and bringing musical and emotional nuances to the performance, she began studying with her parents and, afterward, some of the ballet greats. Her tutors include Victoria Cassan, of the Anna Pavlova Company; Alexandra Danilova, of the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg; Igor Schwezoff, of St. Petersburg and New York; and Joan Hewson, in London. Perlman also performed for a season at the Starlight Theatre in Kansas City.

She spent two summers studying with the National School of Ballet in Canada. During her time there, instructors told her that her physique, which is more short and compact than most ballerinas, would never allow her to have the length of line to do solos.

“I enjoyed performing,” she says, “but they gave me a realistic picture of what I was up against. It was hard to hear, but knowing that really directed me into teaching and choreography.” She also learned modern dance, and she now incorporates that into her choreography as well.

One important lesson she passes on to students is that ballet requires discipline in all areas. “One purpose of ballet is the development of a healthy body,” she says. “The physical demands are intensive. It takes a tremendous amount of physical stamina that has to be built up gradually.”

Ballet as exercise is one class Perlman still teaches; she modifies it for bodies of people who have started late or who are older. She’s learned that “there’s a point beyond which you cannot push,” she says. “Still, it’s fun and great exercise.”

Working as a choreographer and teacher helps Perlman keep on top of things. “This profession keeps me mentally sharp,” she says. “I have to plan what I want to achieve, what impression I want to make.”

And she still loves working with her class of more advanced students. “The work centers me,” she says. “I love walking into the studio and getting totally absorbed in what I’m doing. It helps me be healthy in all ways.”

For Perlman, complete retirement will happen when she’s no longer able to physically to go to work. But even that won’t mean she won’t be involved; it will just mean she’s no longer going to the studio.

“I have plenty to do,” she says. “No matter what, I will always be interested in the arts — ballet, dance, music, beauty and movement as an art — as well as sharing what I can with others. . . . I love to read and participate in tai chi and yoga. I love animals, especially my terrier, Kinsey. I love to watch horses. They are such beautiful animals.”

Discipline and enthusiasm are two of the most important ingredients to finding work that fulfills, according to Perlman: “You must find something you’re enthusiastic about. Then, you must have discipline to do the work you are enthusiastic about. In other areas, I can be quite lazy. I might have been in total slovenliness if not for the enthusiasm I have for my work.”

Needless to say, it’s hard to imagine this small, intelligent, energetic, and well-spoken woman to ever be slovenly.

John Whiteside

John Whiteside, 68, is an attorney who figures out problems and helps provide logical solutions. By his definition of retirement, he says, “I may cease to practice my profession full-time some day, but I will never retire from being a lawyer. My profession will always affect me. I will always ask, ‘Can I prove that? Who would I call as a witness to say I was there and saw that happen?’”

A former Columbia municipal judge, Whiteside now serves as a guardian ad litem for children and psychiatric patients. “When I was a judge, I was an umpire — calling balls, strikes, safes, and outs” he says. “I missed playing. The judge is the umpire, and I wanted to play first base.”

He’s been a proactive player for 14 years seeking creative solutions for difficult situations. As guardian ad litem, Whiteside is a voice for kids in distress. This is often in divorce proceedings or custody battles.

“A guardian ad litem is an officer of the court who relays the wishes of the individual they’re representing and gives recommendations as to the best course of action for the child,” he says.

Whiteside explained many times there are informal arrangements made for neighbors, friends, godparents, or others to take care of children. In one case, a young man had lived with his godparents since birth and considered them his parents. They treated him like their child. He had his own room, clothes, food and all he needed. The biological parents weren’t involved.

“Then one of the parents, who was like a stranger to him, snatched him overnight,” he says. “He was sleeping on the floor and getting to school only half the time. The godparents filed a petition for guardianship.”

Whiteside was the representative for the child. He went to several hearings and then suggested the godparents become emergency guardians and the young man be returned to them.

“I had to first find out, what does the child want?” Whiteside says. “Then, what does the child need? Also, what were the parents doing when nobody was watching? In this case, nothing,” Whiteside says. “No finances. No food. No shelter. No clothing. However, the godparents were fully providing all that, plus love. The judge agreed with me and the boy was returned home to his godparents.”

The people in his cases inspire Whiteside the most. “There are kids falling through the air and someone, for no other reason than love, reaches out and catches them,” he says. “I get to watch that happen. I’m constantly inspired by the selfless love of human beings.”

Now, in the later stages of his career, Whiteside looks at his job — and everything else — with a new appreciation. Thirty years ago, he had cancer. “I was afraid I would never recover from that,” he says. “I’d look out the hospital window and think the luckiest people in the world were the ones headed down Broadway to work. Now every day I get to work is a blessing for me.”

Whiteside is now cancer-free and healthy. His goal is to be useful. “I like being part of the legal process,” he says. “It’s a process in which I have great faith. That’s based on daily observation over the last 33-plus years. There is a judge who makes the final decision, but if I’ve done my job and fulfilled my responsibility, then it’s going to turn out like it’s supposed to.”

Whiteside lives in Rocheport, above the river. He enjoys spending time with his wife, two daughters, and grandchildren. After living in Columbia, they wanted to downsize to a smaller home in a smaller community near friends. It’s where he plans to stay put.