First and Goal: How MU Athletics Can Help Turn the School Around

At 6:14 in the evening on November 7, 2015, MU’s Legion of Black Collegians posted a tweet with two pictures. One was a photo of 31 black MU football players standing, arms locked, with Jonathan Butler, the MU graduate student who was by then on the fourth day of a hunger strike. The other was a screenshot of an iPhone note: “The athletes of color on the University of Missouri football team truly believe ‘Injustice Anywhere is a threat to Justice Everywhere” We will no longer participate in any football related activities until President Tim Wolfe resigns or is removed due to his negligence toward marginalized students’ experiences. WE ARE UNITED!!!!!”

Needless to say, the team’s strike drew a fair amount of attention. Wolfe resigned two days later. The football team did indeed play their next game, beating BYU 20–16 at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City for their fifth and final win of the season. The following spring, MU announced they were going to have to make budget cuts in the wake of low enrollment and further cuts in state appropriations. Several similar announcements have followed since.

MU’s athletic program is the most widely recognizable facet of the school’s brand by a wide margin; the same is true of any SEC school. It brings alumni back to campus throughout the year for tailgates and Homecoming, and it spurs donations and accrues goodwill. MU’s student–athletes serve as de facto ambassadors at every event they travel to. And, for what it’s worth, when I was 18 years old and trying to figure out where I wanted to go to college, I was intoxicated by the size of the MU’s football stadium and the prospect of watching SEC sports in-person for four years.

MU athletics have come to occupy a central part in the narrative of the November 2015 campus protests. Without the football team’s participation, it’s hard to imagine that the protests would have gotten the results that they did. And while university officials have said from the beginning that the protests aren’t solely responsible for the school’s enrollment decline and subsequent funding shortage — demographic changes in higher education and changes to neighboring schools’ recruitment strategies exacerbated the bubble-burst effect — the two have become inextricably linked in public consciousness: You can’t talk about the enrollment problem without talking about the protests, and you can’t talk about the protests without talking about athletics.

Fair or not, that’s not necessarily a bad thing for MU. Athletics may be exactly what they need to turn things around.

Making Money to Spend Money

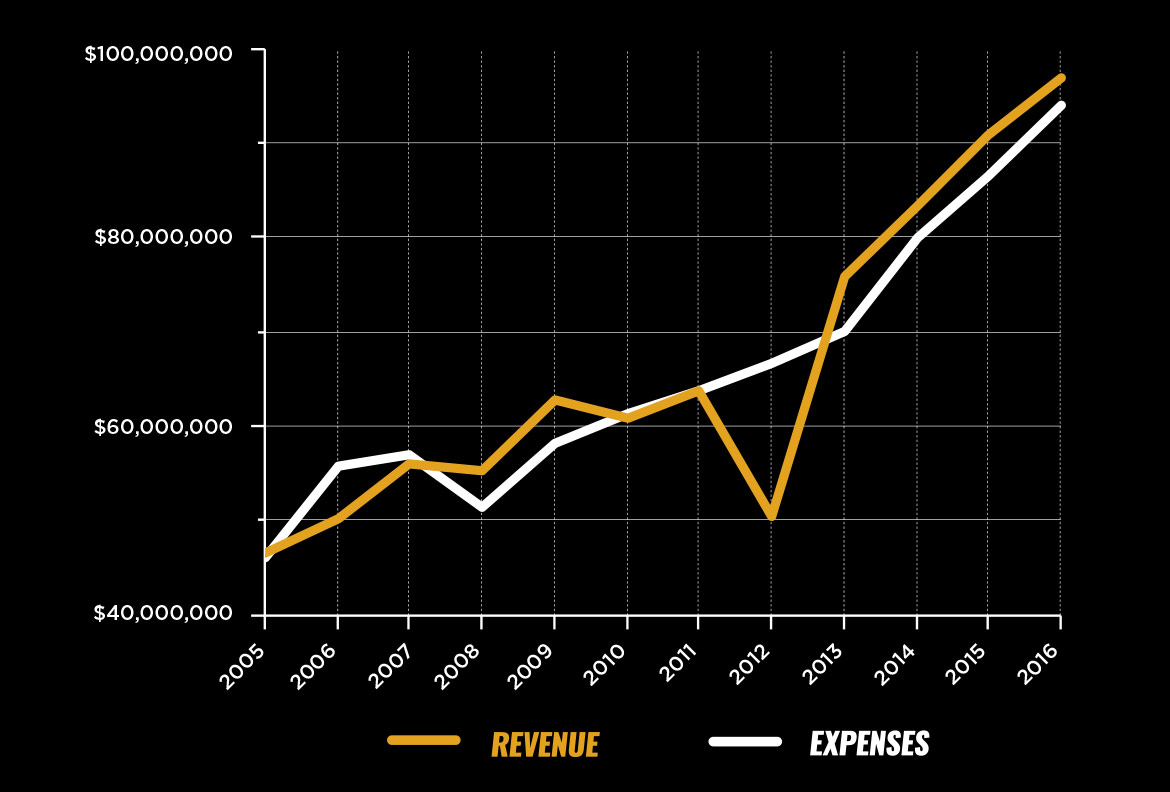

For all the financial sputtering at the university, the MU Athletic Department had the two best funding years in its history in 2015 and 2016. Last year, the department brought in a record $97.2 million in revenue, which topped the previous record of $91.2 million — set in 2015. Of course, those two were also paired with the two highest spending years in MU athletics history, at $86.8 million in 2015 and $94.3 million in 2016 (see graph below).

Such is life in the SEC. The biggest revenue generator in college sports is Texas A&M, a school that made the jump from the Big 12 to the SEC the same year that MU did. Texas A&M’s athletic department brought in $194,388,450 last year. Of the top 15 schools in sports revenue, 9 are from the SEC, according to data compiled by USA Today. (MU ranks 30th overall, second lowest among the SEC schools listed.)

“One of the things that’s often a misconception with people, whether they’re inside or outside the university, is that the athletic department is funded by the university,” says Gary Ward, MU’s vice chancellor for operations. “But it’s the same way it is with our residential life halls, dining halls, hospital, parking garages — they don’t receive any money from state appropriations and they don’t receive any money from student tuition. They have to make their own dollars.”

Before moving to the SEC, MU’s athletic department ran generally around the break-even point — in 2011, their last full year in the Big 12, they brought in $64.1 million in revenue and had $64.1 million in expenses. The revenue jump is largely thanks to school’s TV rights, which are now sold to the SEC Network. For most colleges across the country, athletic programs operate the way MU did in the Big 12: around the break-even point, sometimes dipping into the red or ending up in the black. Not so in the SEC. Being in the conference is a commitment to spending more money than anyone else in exchange for making more money than anyone else — and having a higher national profile.

The athletic department, in fact, gives more back to the university than it gets. A “budget frequently asked questions” page on the MU Chancellor’s website says athletics pays “somewhere in the neighborhood of $15 million” for the tuition and fees of student–athletes, a number also quoted by MU Athletic Director Jim Sterk.

Sterk took over as AD in August 2016 following the abrupt departure of Mack Rhoades, who left to take the same position at Baylor after just 14 (eventful) months as the department’s top administrator. “There’s a lot of learning and a lot of catching up to do when you come into a position like this,” Sterk says. “Basically, I spent a lot of time meeting with staff.”

Sterk commissioned his department to do five SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analyses for student experience, facilities, personnel, resource acquisition, and communication and politics. He also met with coaches, including first year football coach Barry Odom. That meeting, and another with former coach Gary Pinkel, led Sterk to fully embrace a project that had been languishing on the department’s priorities list for more than two years: a stadium expansion behind the stadium’s south end zone, the biggest facilities upgrade since the Missouri Athletic Training Center opened in 2008. The plans include coaches’ offices, a new locker room, a new weight room, and a new player lounge. “It’s like why universities build rec centers and student centers,” Sterk says. “It’s attracting athletes to your particular program. I think you need to have competitive facilities so students are attracted and want to come.”

And when you’re competing for recruits with the Alabamas and Texas A&Ms of the world, you better be ready to raise some money. The project is estimated to cost $95 million to $100 million. The opening date is still a ways off— Sterk hopes to have the expansion done by the start of the 2019 season — but donors are responding now. The department has raised nearly $50 million, and at the time of this writing, Sterk expected the project to be formally approved by the UM System Board of Curators at the end of July.

“This is the same kind of thing that I think football needed,” Sterk says. “And it’s not just me saying that — it’s the commissioner of the SEC and others. It was selling that vision of what we could be, and I think people want us to be able to compete in the SEC. It’s a very difficult conference, a very competitive conference. So we needed to make investments to be able to compete.”

The fundraising momentum created by the athletic department over the last two years seems astonishing when you remember that the football team, to say nothing of the lingering stigma from November 2015, is coming off its second consecutive season without a bowl appearance and the men’s basketball team went 10–21. The south end zone project has been a boon to the football program’s reputation among donors, but it’s arguably less impressive than Sterk’s hiring of Cuonzo Martin to be the new men’s basketball coach — Martin, a St. Louis native, put together an elite recruiting class that has the team on short lists ranking the nation’s top basketball contenders (including Kansas). MU’s most public-facing department is on the upswing again.

Brian White, the athletic department’s deputy athletic director for external relations, says the conversations with donors are changing. “When you’re having a gift conversation, it’s not like you just show up and ask for money,” he says. “There’s a long relationship beforehand, and a lot of that is because they have to feel OK about what they’re investing in. They have to feel great about what they’re investing in. So a lot of them may not feel great about everything that happened, or they may not feel great about the way things are at Mizzou right now, but they buy into the vision of what their gift is going to do for the school they love. I think that’s one unifying thing from their school.”

Rebuilding a Cornerstone

Of course, the optics of building a $90 million football stadium addition while the university is laying people off are not great. With money tight, MU has to answer for every project, every program, every move made.

“And that’s rightfully so,” Gary Ward says. “Our friends and taxpayers want to know. And I think those are legitimate questions and we should answer them. . . . I’ve been doing public higher education now for a little over 30 years. I don’t think we’ve done the best job of teaching our constituents the difference between the teaching and research aspects of a university and the auxiliary aspects of a university.”

But Sterk and others think that the athletic department can do more than not drain the university’s budget. Having a popular and successful athletics program is going to be a pivotal part of MU’s recovery strategy — sports could bring back some of the dollars the school has lost over the last two years.

“What other way do you get your brand on TV for four hours?” Ward asks. “Where else do you get that kind of exposure for an institution, other than the athletic department?”

There’s some direct ways that sports can help take the sting out of budget cuts — take, for example, the new residential life policy to rent out dorm suites for $120 per night on home game weekends. But there are also some less obvious ways, like attracting more walk-on student–athletes who are willing to pay full tuition for the chance to play at MU. Sports contribute to the less quantifiable “campus culture,” and while it’s not a direct causal relationship, it’s also probably no simple coincidence that MU football’s most successful 10-year stretch, 2005 to 2015, also coincided with the biggest enrollment increase in school history. Smaller schools routinely subsidize their athletic programs, despite the fact that they operate at a consistent loss. The side benefits outweigh the direct costs.

“Having a basketball program that went from having like a 200-something recruiting class to having a top-five recruiting class” — Sterk laughs here — “that helps. I’ve had alums say, ‘Yeah, I just had my daughter commit somewhere and she heard about all this basketball stuff at Mizzou, and she’s wondering if she should have gone there,’ you know. I hear those anecdotes as I meet with people around the state. So it’s important — athletics can have a role in engaging a community and engaging a state, so that’s what I think our role is.”

Sterk says the department is also working with MU Extension to develop their presence in “every county in the state”; in January, Sterk hired former MU football player Howard Richards to be assistant athletics director for community relations in St. Louis, an area where enrollment has softened.

Obviously, the more MU wins, the bigger the benefits will be. In an email, Pelema Morrice, MU’s vice chancellor for enrollment, wrote: “When our teams do well, our national exposure does increase and we have experienced increases in applications. We’re always happy when our teams do well because it helps get students interested in learning more about us; students then have an opportunity to better explore what opportunities the university provides for students.”

Winning in the SEC is hard, but when it happens, sports can hold a spell over MU supporters that’s more intense than anything else the university could produce. Academia can feel inaccessible to the general public — the research, the peer reviews, the adjuncts and associates and doctorates and cum laude and dissertations. Most people, at least on some level, understand sports.

“I’m looking forward to this year in a big way,” Sterk says. “I think this fall could be really, really exciting for this program and this university.”