Facing the Nursing Shortage

Fast-paced nursing appeals most to Columbia College student Madelynn Grossman, in an emergency room or as a flight nurse, for example. She chose this career path for the variety of options, the outlet for her caring nature and because the nationwide shortage of nurses makes a post-graduation job almost a guarantee.

“The shortage definitely played into my decision to do nursing,” Grossman says. “Nursing is a field that will always have job openings, and typically nurses are able to find jobs right out of school.”

With the United States in the throes of a nursing shortage, mid-Missouri colleges are expanding their programs and adding accelerated degree paths to attract students like Grossman and get more nurses educated and out in the workforce.

The shortage of registered nurses compared to demand has been predicted and studied for more than a decade, when the health care industry began preparing for the impact of an aging baby-boomer population. The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 brought millions of Americans into the health insurance system starting in 2014, which further increased demand for nursing services.

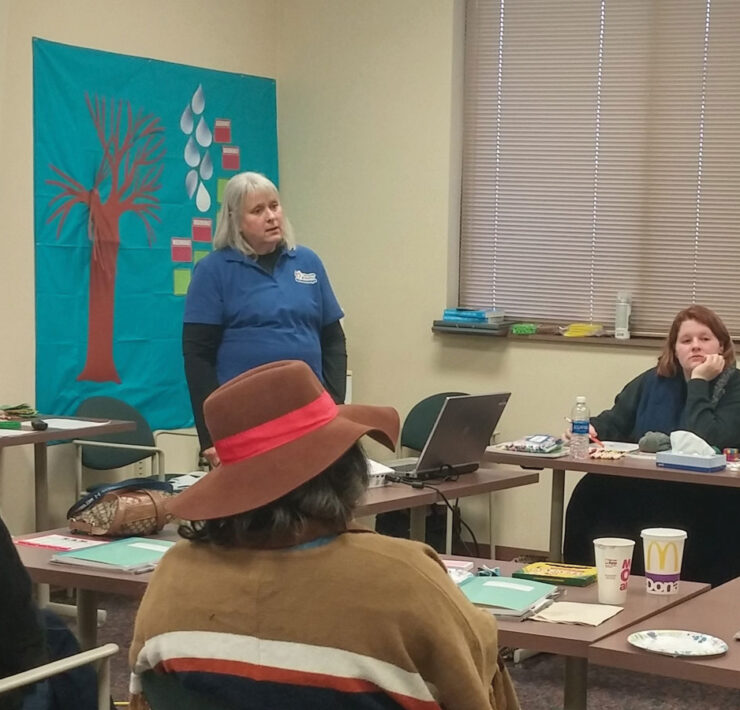

“There will be an exponential need for nurses due to a lot of things, including the aging population and an increase in chronic illnesses,” says Judith Fitzgerald Miller, dean of the Sinclair School of Nursing at the University of Missouri.

Jobs for registered nurses will grow by 19 percent between 2012 and 2022, compared to the 11 percent growth average for all occupations, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That makes it one of the fastest-growing occupations in the country.

The agency projects the RN workforce will grow by nearly 530,000 jobs to 3.24 million from 2012 to 2022. That’s considerable growth but still not enough: Health care industry analysts have predicted a shortfall of more than 500,000 nurses by 2015 and of a staggering 800,000 by 2020. Those numbers reflect the rising demand for care as well as the need to replace retiring nurses.

The retirement rate among RNs is a key factor in the shortage, with 55 percent of the current RN workforce age 50 or older, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. More than 1 million RNs will reach retirement age within the next 10 to 15 years.

Growing demand

Several mid-Missouri colleges are taking steps to expand programs and give more students a path to a nursing career, including Sinclair at MU, Central Methodist University and Columbia College.

Sinclair is the largest of the mid-Missouri schools offering nursing programs, with 1,372 students enrolled in fall 2014.

The school’s program is highly competitive and highly acclaimed, earning the No. 1 spot in a 2014 ranking of nursing schools across the country by CollegeAtlas.org, which evaluates the schools based on affordability, academic quality, accessibility and RN board exam pass rates.

As predicted, abundant jobs are the reality for students graduating with an RN or other nursing degree. Sixty percent of Sinclair graduates had confirmed jobs before graduation, with more than 80 percent staying in Missouri. Many of those graduates stay not only in Missouri but also in Columbia within the MU Health Care system. Of the 75 students who graduated in December 2014, 19 are now practicing at MU Health.

Sinclair’s ability to grow and expand is limited by state funding to MU. The school currently enrolls about 75 students each fall and about 55 each spring and must find creative ways to grow those numbers.

“Until we have more resources from the state to expand facilities, we’re at capacity for undergraduate space in the building,” Miller says, citing the need for additional simulation labs and dedicated practice areas. “We have to do enrollment management to not overextend our space.”

Despite the budget limitations, Miller has been able to expand Sinclair’s enrollment through an increase in graduate programs and an accelerated bachelor’s degree track.

In the accelerated program, students with non-nursing bachelor degrees can complete a Bachelor of Science in Nursing in 14.5 months. The program has expanded in recent years, and today 50 students are accepted into that program each year.

The school also offers an RN to BSN program for nurses with associate degrees, with nearly 65 students currently enrolled. Because that program centers on distance learning, it’s a good option for students already working in the nursing field who want to further their education. Its virtual nature also makes it a good way to increase enrollment without expanding facilities.

Growth in graduate programs has also been substantial, thanks in part to a Doctorate in Nursing Practice program Miller implemented when she joined the school in 2008. The master’s program includes a Master of Science in Nursing with emphasis on education or leadership.

The increased focus on graduate and advanced programs is not only a way to grow Sinclair’s program, but it’s also a strategic move to meet the need for specialists and leaders within the nursing field.

The DNP prepares students for upper-level management positions, and the nursing master’s programs prepare students for faculty roles and advanced nursing positions such as nurse practitioner and clinical specialist.

A new nursing innovations and leadership focus in the DNP program rolled out in fall 2014. It’s designed for master’s-level nurses interested in organizational and executive leadership, clinical setting leadership, academic and research opportunities and health policy design.

The school also has a traditional Ph.D. program geared toward research and leadership roles.

“We’ve put our energy into preparing teachers and leaders at the doctoral level,” Miller says.

Accelerated programs

Columbia College offers an Associate of Science in Nursing, which qualifies students as an RN, as well as an RN to BSN program.

Grossman says the school’s smaller size and the ability to graduate after two years with an RN were key factors in her decision to pursue the program.

“It allows for people to start working immediately, which is necessary for me,” she says.

The remaining courses toward the BSN can be done online over two years.

Central Methodist University started its own accelerated BSN program in May 2013 at its Columbia location. The first class graduated in July 2014 with 10 students, and 13 more are currently enrolled.

The school plans to admit 15 students per year over the next few years, according to Angie Cornelius, coordinator of the accelerated BSN and MSN programs and associate professor of nursing.

“With the creation of and investment in the new accelerated BSN program, our goal was to specifically cater to a new and different market of students and increase the number of BSN graduates in mid-Missouri,” she says.

Demand is indeed growing for BSN-prepared nurses, and CMU’s graduates are helping fill the gap. Cornelius says 100 percent of the first accelerated BSN grads accepted job offers for nursing positions, with 80 percent of them going to mid-Missouri hospitals.

Demand is highest in acute care hospital settings, she says, and the overwhelming majority of CMU students start out in that area.

Statistics from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing back up that claim. A recent study showed 56 percent of nurses practice in a hospital setting, with 9 percent in ambulatory care settings, 6 percent in nursing homes or assisted living facilities and 6 percent in home health. Other areas offering nursing jobs include correctional facilities, academic settings, public health programs and insurance or regulatory organizations.

From a student’s perspective, acute care is attractive for its fast pace and variety, Grossman says.

Future gap

Although the job market for nurses remains strong locally, Cornelius says her students are seeing a tighter market in metro areas such as St. Louis and Kansas City.

CMU took a big step toward further expansion in August, when the school broke ground on a $6.5 million Center for Allied Health facility that will house the nursing and athletic training programs once it’s completed. The school is also undertaking an $8.5 million renovation of a 50-year-old science building.

“The new Center for Allied Health and a renovated Stedman Hall of Science will allow us to prepare greater numbers of students to make a difference in the world,” CMU President Roger Drake says.

Mid-Missouri schools are taking steps to help alleviate the nursing gap, but the numbers show the shortage is still a long-term challenge.

For example, nursing school enrollment across the United States is not growing fast enough to meet anticipated demand, according to the AACN. Nursing programs saw a 2.6 percent enrollment increase in 2013, the AACN reports, which is not enough to meet the growing demand for nurses.

Another factor in the shortage is the aging of the nurse population itself. The supply of RNs hit a plateau in 2007 and has continued to decline from there, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

That trend impacts not only clinical settings but also education. Nearly three-fourths of full-time nursing program faculty members are age 50 or older, which reflects that younger nurses are choosing better-paying clinical jobs over full-time faculty positions.