A Taste of Nuclear Medicine

As drugs go, technetium-99m has a relatively low public profile. Neither technetium-99m — called Tc-99m for short — nor its parent isotope, molybdenum-99, enjoy wide name recognition.

Yet for all its relative anonymity, Tc-99m generally is considered a diagnostic powerhouse. It’s used in medical scans to help evaluate heart disease and for myriad other tests, such as brain and bone scans. In fact, about 80 percent of nuclear medicine exams throughout the world use Tc-99m. In round numbers, that’s 30 million exams per year, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Nearly half of those doses — between 14 and 15 million annually, or roughly 50,000 each day — are used for U.S. patients, the FDA says.

It’s a large market. And Columbia soon might be at its core, serving as a significant domestic supplier of the radioisotope molybdenum-99 (Mo-99) from which Tc-99m is harvested.

Two companies have plans in the works to establish Columbia operations that would produce Mo-99 for commercial use. Most visible is a Northwest Medical Isotopes, LLC proposal to build a Mo-99 processing plant in Columbia’s Discovery Ridge Research Park. The Oregon-based startup proposes to join forces with the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) and at least two other research reactors to produce enough uranium-based Mo-99 to meet about half of North America’s demand for the medical radioisotope. MURR also has a research agreement with another company pursuing Mo-99 production technologies, NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes, LLC. NorthStar, a Wisconsin-based biotechnology company, received funding about a year ago from the the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration to support its plan to work with MURR to produce Mo-99 without using uranium as a source material.

University officials are tight-lipped about specifics on Mo-99 production in Columbia. Still, they acknowledge MURR is collaborating with both NWMI and NorthStar, and welcome partnerships that make use of the university’s nuclear resources and expertise.

“We are positioned to work with both,” says Ken Brooks, MURR’s associate director. “It’s not an either-or moment.”

Despite its status as the source of the world’s most widely used medical isotope, Mo-99 currently is not produced in commercial quantities within the United States. That wasn’t always the case. In fact, MURR produced Mo-99 for more than 15 years starting in the late 1960s. During the 1980s, a Cintichem Inc. reactor in Tuxedo, New York, provided a U.S. supply, but the reactor developed a leak in 1989 and was shut down, a National Research Council report notes. Since then, Mo-99 production has moved abroad, with much of America’s supply coming from reactors in Canada and the Netherlands.

These and other producers create most Mo-99 by irradiating highly enriched uranium provided by the United States, says Orhan Suleiman, a U.S. FDA senior science policy adviser who focuses on Mo-99 production. But that highly enriched uranium is “basically weapons-grade uranium,” Suleiman says, sparking nuclear proliferation concerns. Congressional proliferation worries found expression in the American Medical Isotope Act of 2012. The bill supports the development of U.S. sources of Mo-99 using methods that don’t require highly enriched uranium and phases out the export of such uranium for medical isotope production within seven years of enactment.

The drive for domestic Mo-99 production took on additional momentum when the Canadian government announced its aging National Research Universal (NRU) reactor would no longer produce the isotope after 2016. The NRU has at times produced as much as 67 percent of the world’s Mo-99 supply, and NRU shutdowns in 2007 and 2009 prompted worldwide Mo-99 shortages, Suleiman says. Moreover, a French reactor supplying Mo-99 will shut down permanently in 2015, and a Belgian reactor will go offline for about one and a half years starting in early 2015 while it undergoes refurbishment.

What’s the result of these proliferation and production concerns? “There’s a lot of pressure to have some production capacity in the United States,” Suleiman says.

Center of production

Domestic producers are proposing to provide that capacity in various ways.

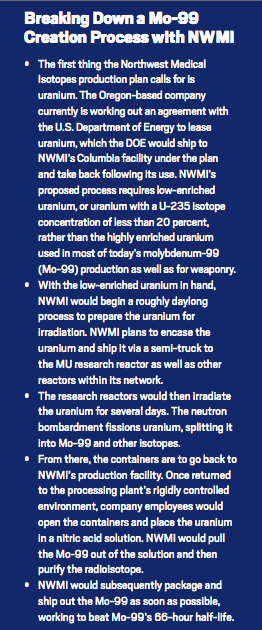

NWMI plans to build a 50,000-square-foot radioisotope production center on nearly 7.5 acres the company has leased in Discovery Ridge, a developing research park at Discovery Parkway and U.S. Highway 63 owned by MU. The $50 million facility, which still needs state, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and FDA approvals, would produce only Mo-99, says NWMI CEO Nicholas Fowler. Fowler says he hopes to receive NRC approval to build the facility by the fall of 2015 and aims to have the building complete and start Mo-99 production in late 2016.

Once in operation, NWMI’s Columbia facility would be at the heart of a Mo-99 production supply network designed to meet at least 50 percent of North America’s demand for the isotope. The proposed facility would extract and purify Mo-99 from irradiated uranium supplied by nuclear reactors across the country, including MURR, the Oregon State University reactor and a third reactor whose name Fowler says he is not yet willing to disclose.

“We’re envisioning three, but we have the ability to add more,” says Carolyn Haass, NWMI vice president and technical program director.

For MURR’s part, Brooks says merely that “there have been initial discussions about how we can work with them [NWMI] in the future.” Whichever reactors act as NWMI’s partners, the company plans to irradiate low-enriched uranium — rather than the highly enriched uranium whose use the federal government is trying to rein in — to produce Mo-99. Although it would use a well-known fission technique to create the isotope, Fowler says NWMI’s proposed process is innovative in that it could generate commercial quantities of Mo-99 using small research reactors such as MURR’s 10-megawatt facility. The company plans to use a unique design for its target, the name given to the material containing the uranium slated to be irradiated in a nuclear reactor, to be able to make use of the smaller reactors, according to a NWMI press release.

As the home of MURR and an experienced high-technology workforce, Columbia was a natural site for the new production facility, Fowler says. Moreover, NWMI had an existing research relationship with MURR, which Fowler says was a “huge piece of our decision to be here.” Columbia’s central geographic location as well as the warm welcome that university and civic leaders gave the proposal also influenced NWMI’s site selection, Fowler says. The Missouri Department of Economic Development is offering NWMI an economic incentive package for its project, which the company predicts will create nearly 70 high-skill jobs.

Steve Wyatt, MU’s vice provost for economic development, says the university has been looking for ways to build upon its nuclear and medical facility strengths. University leaders are excited at the opportunity the production facility presents to develop those strengths while serving the national health care system, Wyatt says, and will continue to explore other possibilities.

“We hope that opens up other opportunities,” Wyatt says.

Alternative technology

Another Mo-99 opportunity already is at MURR’s fingertips. NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes has for years been pursuing a couple of alternative Mo-99 production technologies, aided by National Nuclear Security Administration cost-share arrangements worth up to $15.5 million in federal funding. Included in that total is $10.9 million awarded by the NNSA last November to support NorthStar’s work with MURR to develop a commercially viable process for producing Mo-99 without using uranium as a source material. Although university officials describe MURR’s work with NorthStar as a “research and business development project,” a NorthStar representative says the company is ready to go.

“We’ve moved beyond proof of concept, and our technology works,” says Edmond J. Fennell, the company’s vice president of business development. “…We’re ready to go.”

The NorthStar Mo-99 development process based in Columbia calls for producing the isotope using a “neutron capture” technique. Instead of uranium, NorthStar’s process starts with molybdenum-98 (Mo-98) — a stable molybdenum isotope found in nature — that would be irradiated under the plan to produce Mo-99 along with a range of other molybdenum isotopes, Fennell says. MURR would then dissolve the irradiated molybdenum into a solution and deliver it to NorthStar’s on-site dispensing area, where the company would transfer the Mo-99 solution to smaller containers for shipment. From there, NorthStar would ship the Mo-99 to nuclear pharmacies equipped with the company’s proprietary technetium extracting technology, which captures Tc-99m from the Mo-99 solution with commercial-grade efficiency. The only uranium used would be that required to operate the reactor, under NorthStar’s plan.

NorthStar has about 1,800 square feet at the MURR site, and is currently installing Mo-99 processing and dispensing equipment there, Fennell says. NorthStar has applied for FDA approval of its project, which it must receive before beginning commercial production. Fennell says NorthStar expects to begin producing small quantities of Mo-99 by late 2015. By the end of 2016, NorthStar expects to be able to supply about half the U.S. demand for Mo-99, he adds.

“Our strategy is to start small and then ramp up,” Fennell says.

University officials shy away from discussing MURR’s role in future Mo-99 production, saying the timeline to move from proposed to actual production is lengthy and includes many steps. The FDA’s Suleiman is more forthcoming.

“The University of Missouri has actually been a focal point,” Suleiman says.