The Rock that Built Us

Just about everything you see built in Columbia — from the University of Missouri’s iconic columns and white campus to the fine brick homes on Broadway and buildings in between — came from the area’s quarries. At one time, Columbia had upward of 30 quarries and several brickworks. Today, all the brickyards are closed, and only three working quarries remain, none of which continue to produce building blocks.

Yet, local quarries continue to turn out the stone that literally supports your entire life: from the foundations of your home, your favorite retail space, what surrounds the water and sewage lines leading into every building, the material for every road, street, sidewalk, as well as the trails in the park, even agriculture products. The list is seems endless.

But many people still think of quarries as dirty, dusty, dangerous places from the past, an image Doug Mertens, one of the owners of Mid-Missouri Limestone, which operates a quarry in northern Boone County, is busy dispelling.

“It’s a misunderstood industry,” says Mertens, whose family owns and operates five quarries in the central Missouri area. “People think we’re pillaging the earth, but we’re not. We’re providing a product that supports our way of life, everywhere, all the time.”

For an example, Mertens points to Battle High School.

“We supplied the vast majority of the aggregate necessary to make that beautiful building, but all people see is that beautiful building,” he says. That’s because the rock that came out of the 200-acre quarry in Sturgeon and another Mid-Missouri Limestone quarry in Millersburg is under the building and the parking lot and provides drainage and the rock for all the asphalt paving. Mid-Missouri Limestone provided 55,000 tons, roughly 3,235 dump-truck loads, of aggregate for that project.

Rocking the economy

These quarries are a crucial component of Columbia’s economic development and save us money, whether we know it or not.

“It’s infrastructure,” Mertens says. Rock is part of every single construction project, from homes to roads and bridges, and it’s heavy and expensive to transport, which means Boone County benefits from having materials available locally.

Here’s where rock goes:

- Roads, whether made of asphalt or concrete, are made up primarily of rock. One mile of a typical, two-lane asphalt highway requires roughly 25,000 tons of aggregate, according to a 2006 DNR publication.

- Homes and buildings: Each home can include more than 229 tons of rock, for drainage, the foundation and concrete, according to the American Geological Institute.

- Cities and counties buy rock for drainage operations, conservation and water management, laying water and sewage lines and road and street building and upkeep.

- Agricultural lime used on farm fields.

Past woes

Up until 1971, quarries were lightly regulated, according to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Land Reclamation website. As one quarry expert says, almost anyone could — and did — start digging on any land they owned.

Columbia residents might recall the 2002 incidents when Boone Quarries-East on Creasy Springs faced complaints about blasts that sent rocks into neighboring yards. Then there are the recent complaints against the operator of Boone Quarries, Con-Agg of MO LLC, which operates Subtera, an underground storage facility, where MU says about 300,000 books are a potential loss due to mold.

The website of the U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration shows all of Boone County’s quarries have received citations over the years, though none are classified as serious. Mid-Missouri Limestone received a MSHA safety certificate award in 2012.

“It’s nearly impossible,” Mertens says,” for a quarry to not have a citation.” That, he says, is because local, county, state and federal agencies have taken steps to make sure quarries are regulated, monitored and inspected.

In general, Mertens says he supports the oversight, noting it keeps everyone safe. After all, he lives in the area, and all of his employees are more than just worker; they are neighbors and friends.

Getting up

These days, getting into the quarry isn’t easy. Anyone coming on the premises must be accompanied at all times; employees must receive 24 hours of training within 90 days and continued training. The perimeter of the quarry pit is guarded by a row of boulders surrounded by a wide berm of warm-season grasses, and Mertens makes sure a reporter and a photographer seeking a better view of the pit stay within legal areas.

At the quarry, Mertens points out the monitoring devices and describes the EPA regulations for water runoff and air quality and fees paid to ensure testing and compliance and the efforts his firm has made to meet and exceed those requirements.

Now, quarries are required to reclaim the land after mining. The result, Mertens says, can be a place that looks even better than before, a place that becomes, in some cases, a park instead of just a hole in the ground. Anyone who has ever walked by the Quarry Heights Neighborhood park near the MKT Trail can see how a former quarry can be transformed. The area was named to Columbia’s Most Notable Properties List in 2009.

At Mid-Missouri Limestone in Sturgeon, Mertens points out the high berm and tree plantings, where the nearest neighbor is nearly out of sight. Along the way, he notes the one-mile stretch of road his firm transformed from a one-lane unpaved county road into a two-lane smooth stretch of a highway-like road, built to bolster his firm’s request for a conditional-use permit from Boone County when it expanded operations in 1999. He points out the new homes built along that road since the quarry upgraded the road and adds that those homeowners apparently didn’t mind that the road led to a quarry.

In Columbia, both Boone Quarries don’t have the luxury of being far from town; the city has grown up around both the Creasy Springs and Stadium locations. Other quarries close to town, the ones on Rock Quarry Road and by the MKT Trail, closed decades ago.

Dangers to quarries

With quarry products so integral to daily life, the industry is vulnerable to the economy’s ups and downs. When housing and commercial building took a hit, so did Missouri’s $1 billion a year limestone industry, says Steve Rudloff, executive manager of the Missouri Limestone Producer Association. Limestone is mined in 92 of Missouri’s 114 counties and employs roughly 2,500 people statewide. But during the economic slump of 2008 and 2009, Rudloff says, some quarries saw a 30 percent reduction in sales followed by another year with the same kind of fall in sales.

When governments, from local cities to counties to the federal government, cut back on asphalting, paving and other infrastructure expenditures, Missouri’s limestone quarries take that hit, too. And though housing starts are recovering, the struggle to find funding for infrastructure, from roads to bridges, continues to make the news almost daily.

In Missouri, the outlook is bleak for road construction. The Missouri Department of Transportation news release states due to fuel efficiency, less driving and increased material costs, MODOT has lost roughly half of its purchasing power since 1992, the last time the 17-cent-per-gallon state fuel tax was increased. The release notes now that 17 cents equals about 8 cents in buying power and continues to plummet yearly.

In short, Rudloff says, MODOT has very little money for new construction projects.

Better times

Some of Columbia’s former quarries were victims of their own success, the best rock taken during the 1800s and early 1900s. Although no shaped blocks are quarried locally, some are still produced elsewhere in the state; the Columbia Public Library is built of Missouri quarried stone.

Other quarries were probably mom-and-pops that went out of business. That’s how Liz Kennedy, one of the owners of Columbia Brick and Tile, described the firm that was the city’s last remaining brickwork, prior to its 1984 closure.

“It was kind of a family thing,” she says. Her father, Fred Kennedy, bought into the business with William Powell in 1950. The firm could turn out 35,000 bricks a day and employed 35 workers, according to a 1971 newspaper article. With automation, other brick manufacturers could produce bricks cheaper and with a more uniform color, Kennedy says.

The quarry, she says, was located roughly where Lowe’s and Walmart on Conley Road are today. In the 1940s the brickworks were called Edwards-Conley Brick and Tile, owned by W.E. Edwards and Sanford Conley.

But in the 1980s, the Columbia brickworks with its hive furnaces and use of locally quarried clay and the resulting natural color variations simply couldn’t compete. Kennedy says the company faced rising costs, increased competition and regulations, and she and her brother, Jack Kennedy, decided to close the company. But in the yard of her brick home with its many brick walkways, she still has stacks the eight different kinds of bricks the company made, from face brick to fire brick to red tile.

More local quarry closures aren’t expected, though. Instead, Rudloff says he expects to continue to see smaller operations bought out by larger operations.

As for Mertens, he’s not looking back but ahead. His firm upgraded operations at the quarry in 2006. “We believe Boone County to be a growing market, and Columbia is a growth market,” he says. “We’re here to stay.”

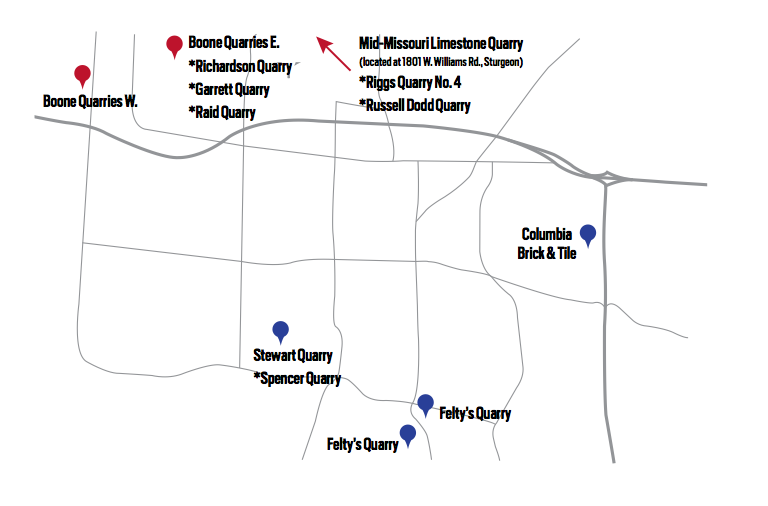

Where They Are Now?

WHERE IT WAS: Felty’s Quarry once owned by John N. Fellows, a 1893 MU grad, was probably where the 1983 Rock Quarry Building is now, just outside Capen Park. Described as located at South College Avenue, it may have included the quarry across the street as well, where the 1993 Museum Support Building now stands. MU publications from the 1960s and 1970s show it as a former quarry and a popular place for students to enjoy rest and recreation.

WHAT IT BUILT: Fellows says his quarry provided rock for the MU white campus, according to The Missouri Alumnus, December 1957.

WHERE IT IS: The Richardson Quarry, according to a 1904 publication, has also been called the Garrett Quarry and the Raid Quarry. It seems to be at the same location as Boone Quarries-East on Creasy Springs.

WHAT IT BUILT: A 1904 document states the Richardson Quarry, now Boone Quarries-East, provided rock for the white campus.

WHERE IT IS: Boone Quarries-West, located on Stadium Drive, has been operational since 1954.

WHERE IT IS: The Mid-Missouri Limestone quarry is also known as the Riggs Quarry No. 4. It is at 1801 W. Williams Road in Sturgeon. Mertens says the quarry also was known as the Russell Dodd quarry.

WHAT IT BUILT: No historical information is available about a specific building its materials were used for. The quarry did, however, produce Burlington rock, which was often used for exterior building blocks.

WHERE IT WAS: The Stewart Quarry, near the MKT Trail, was once owned by J.A. Stewart, the namesake of Stewart Road, and was operated as a quarry until a spring made that impossible. In 1950, Hirst Mendenhall of Boone Realty Corp. bought the quarry and deeded it to the Quarry Heights subdivision for use as a park. It was also previously known as the Spencer Quarry.

WHAT WAS BUILT: A 1915 publication states the Stewart quarry also provided rock for the white campus and the Missouri Capitol. In 1920, this quarry may have been used for building materials for homes on Edgewood. The Missouri Alumnus September 1920 refers to houses on Edgewood being built with materials from the Spencer Quarry, “south of town.

WHERE IT WAS: Columbia Brick and Tile was at 2801 E. Walnut.

WHAT WAS BUILT: From 1930 to 1940, it operated as Edwards-Conley Brick and Tile. An article in the Sunday Missourian, Vol. 5, No. 23, Sunday, Sept. 12, 1971, supplement quoted owner-operator Bill Powell saying Columbia Brick and Tile “supplied almost all the brick in every building on the University Campus with the exception of some of the older ones and the addition to the law school.” The Virginia Building, now the Atkins Center, on Ninth Street was built with bricks from the Edwards-Conley Brick and Tile Co.