Where Hope and Science Collide

- This story originally appeared in the January 2024 health and wellness issue of COMO Magazine.

+5

+5 Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

Where Hope and Science Collide

For those who struggle with infertility, building a family takes them down a grueling path. But for three Columbia couples, it’s been a journey worth taking.

It has been said that bringing a child into the world is the ultimate act of hope. Perhaps that statement has never been truer than at this moment in history.

But what if you can’t conceive or have a successful pregnancy, no matter how hard or how long you try? Hope can quickly turn into despair when dreams are shattered.

Infertility is defined by a couple’s inability to conceive when having unprotected sex frequently for a year or longer. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that roughly one in five women aged 15 to 49 who have never had a child are unable to conceive within one year of attempting to get pregnant.

Couples facing infertility have a range of options these days, from adopting a child to undergoing treatments such as intrauterine insemination (IUI) or in vitro fertilization (IVF). They can choose to use their own sperm and eggs or use donors. The woman can carry the embryo, or the couple can hire a surrogate.

The choices are dizzying. They’re also expensive, with the cost of one cycle of IVF reaching as high as $30,000 or more. Health insurance pays for little, and in most cases, none for treatments. Even traditional adoption comes with a hefty pricetag in Missouri, ranging from $5,000 to $40,000, according to adoption.com.

For some couples, none of these options are within financial reach. Others incur debt that takes years to pay off. That scenario leads to a series of questions: What is the financial, physical, and emotional cost of having a child when conceiving traditionally doesn’t happen?

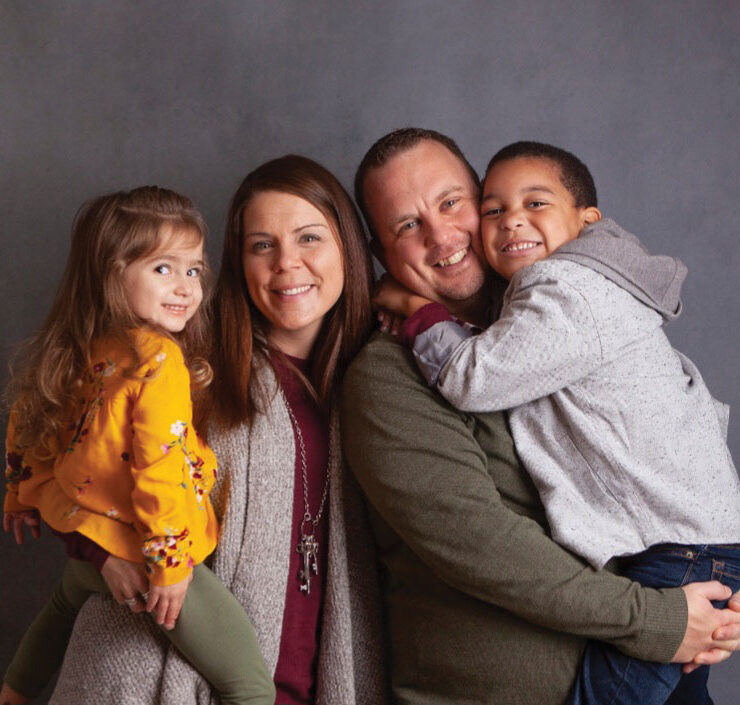

Three local couples agreed to tell their IVF stories. Their circumstances are all unique, but they share three common threads: None of it was easy. None of it was inexpensive. And in the end, none of them let infertility keep them from becoming parents.

Anything but IVF

John and Melissa Miller decided to stop using birth control once they married. Six months went by, then a year. Melissa, a surgical nurse at Boone Health, knew something wasn’t right. The couple booked an appointment with Dr. Gil Wilshire, MD, at Missouri Fertility in Columbia.

“Honestly, when we went into this journey, I thought, ‘We will not do IVF. We’ll do everything but IVF. I’ll do the testing, but that IVF is crazy,’” Melissa says. “From a nursing standpoint, that’s what I thought.”

Bloodwork didn’t show any specific problems. Dr. Wilshire suspected Melissa suffered from polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a condition associated with infertility problems in roughly 70 to 80 percent of women who have it.

John and Melissa started with IUI. This treatment involves gathering as many healthy sperm as possible and injecting them directly into the uterus during the height of ovulation, creating the best chance for sperm to fertilize an egg. The first attempt was unsuccessful. The second never occurred because a drug used to increase egg production resulted in ten or eleven eggs.

“This is when you can end up being an Octomom if it works,” Melissa said. “Dr. Wilshire told me it’s against medical advice to proceed but it was our decision. We opted to hold off. When we met in his office again, I thought we were going to try an IUI for the third time, but he recommended IVF.”

The recommendation wasn’t what they wanted to hear, and not just because of the cost and time commitment. Melissa based her reservations on what she knew about IVF as a nurse. She later realized she had no idea how rough it was.

“Had I known truly what it was like going in, I probably would have been even more shellshocked and said, ‘No,’ honestly, and looked for a different route to having kids,” she says.

John and Melissa did consider other paths, including surrogacy and adoption. John’s dad was adopted, so they understood the value of that option. Ultimately, though, they decided to pursue IVF.

Over and Over Again

A few months before they married in January 2019, David and Kylie Paulsmeyer decided to stop using birth control. Kylie says they weren’t trying to get pregnant, but they also weren’t trying to prevent it. Because Kylie has PCOS and had been on birth control for years, she knew it might take a while to conceive. They started focusing on getting pregnant in October 2019.

“That’s when I started noticing that something may not be right,” Kylie says. “My fertility journey is quite complicated.”

Kylie started with her regular obstetrician, taking a medication that induces ovulation. But an ovarian cyst ruptured and her OB retired, referring her to a specialist. She and her husband underwent three rounds of IUI, conceiving on the third attempt in May 2021. They miscarried six weeks later. After trying two more rounds of IUI without success, they booked an appointment with Dr. Wilshire where he made adjustments. After four more unsuccessful attempts, he told them their best option was IVF.

“I thought, ‘I’ve been doing this for three years at this point. I’m tired of the emotional toll,’” Kylie says. ‘I know we can’t afford it, but this is what we’re going to do.’”

David wasn’t so sure. As a financial professional, it didn’t make sense spending thousands of dollars on something that might happen, after already spending thousands. But after learning about the science behind IVF from an embryologist, he was on board.

David’s not alone. John is also a finance professional who questioned Dr. Wilshire: “I’m handing you this money and there’s no guarantee we’ll get what we’re paying for?” Dr. Wilshire was honest and forthright about unrealistic expectations. There are no guarantees with IVF.

Snowflakes

Ross and Michelle Kasmann’s IVF journey took a different route. Michelle’s vision for her future family developed before she and Ross married in 2010. A friend in college was an international adoptee searching for her biological roots. Michelle imagined a family of biological and adopted children. She and Ross bought a five-bedroom house to fill with them.

After finding out they couldn’t have children, they spent a lot of time with infertility specialists without success. They sought guidance from Bethany Christian Services where their social worker discussed many options for having children. This led to their adoption of their now 10-year-old son, but the process was rife with complications.

Their social worker had also talked to them about “snowflake” adoption, which is the adoption of frozen embryos donated by couples who don’t need the rest of their embryos but don’t want them destroyed.

“We decided that doctors were better than lawyers,” Ross says. “We were so over dealing with the courts. We didn’t feel like our family was complete yet, but we knew we weren’t ready to go back through all that.”

Of course, children of traditional adoption share DNA with people other than you. The same is true for embryo adoption. But the couple chose that over options like using a sperm donor.

“In my mind, that was separating the team,” says Michelle. “This child was going to be biologically both of ours or biologically neither of ours.”

The Kasmanns reviewed family profiles of the embryos and selected one that had two to donate. Their doctor recommended they choose a second family as a backup in case Michelle couldn’t carry either of the first two to term. After all, snowflakes can melt.

Needles and Time

Infertility treatments are a little like what Albert Einstein said about insanity — doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results. But there’s nothing insane about wanting to have children of your own, and IVF is a science that’s always improving. However, based on multitudes of research and experience, the science can be hell.

Here’s generally how IVF works: The woman usually takes birth control for a bit to establish a baseline for her cycle. Once she completes one full ovulation cycle, the ultrasounds begin. So does the extreme commitment to the process. During the process, women will undergo dozens of vaginal ultrasounds which require frequent trips to the doctor’s office.

Then, there are the needles. Although the Kasmanns avoided the earliest stages of the process, none of the couples escaped the needles. There are frequent blood draws to monitor hormone levels. Kylie, who has always been afraid of needles, says she injected herself four times a day in the stomach with follicle-stimulating drugs to spur egg production. And Melissa said she gave herself more injections during IVF than she’s given to patients during her nursing career.

Roughly two weeks before the eggs are harvested, production needs to be suspended in time. Progesterone shots keep the eggs from dropping before they can be retrieved. Because this hormone needs to act quickly, shots are administered with one-and-a-half-inch needles deep into the gluteal muscles, called intramuscular or “IM” injections. Here’s where the three husbands got to assist. Giving your wife shot after shot, searching for a spot that’s not bruised, takes a toll on the husbands as well. After the Millers miscarried the first two transplanted embryos, Melissa waited six months before making a second attempt.

“At that point, I needed a break from the hormones,” she says. “Because when you put the first two embryos in, you have to do two IM injections every single day, then one every day for the next six to eight weeks. Your bottom is so bruised, and you keep on giving injections through those bruises. On top of the mood swings, I just wanted the summer off. I wanted to feel normal. I needed a break.”

When the eggs are retrieved, the woman is sedated. The man’s sperm is harvested and “cleaned,” leaving the most active swimmers to join the eggs for in vitro fertilization. Once fertilized, the embryos are checked for viability. Parents can opt to have them undergo genetic testing as a further step to determining viability. Of course, they incur the significant cost of such testing, but the couples said it’s worth it.

Then, in a rather simple process, one or two embryos are transplanted into the uterus. The IM injections continue until pregnancy is confirmed.

“It’s a big sprint, especially in the beginning,” Kylie says. “Then there’s all the medicine and going back to have your levels checked. After egg retrieval, you need time to heal. But you get calls every other day about how the embryos are doing.”

It’s painful. It’s time-consuming. The science demands precision. Pregnancy is always a hopeful waiting game. But IVF is the wait before the waiting. It can all exact a toll on a relationship.

The Relationship Test

Infertility places a tremendous strain on couples. Just ask Stephanie Parsons, a licensed clinical social worker, therapist, and owner of Counseling Associates, who works with couples experiencing infertility.

“I see quite a bit of depression and grief related to clients who struggle with fertility. Depression over the fear of not ever having a successful pregnancy. Loss related to the loss of a pregnancy or the perceived loss of having a biological family. Couples are often so adversely affected that I also work with clients who are struggling to maintain a healthy relationship as a result of the stressors related to fertility struggles,” Parsons says.

Expectations are a major hurdle. Remember that five-bedroom house the Kasmanns bought to fill with kids?

“You really have to grieve the loss of your expectations of how your family is going to look,” Michelle says. “Once we gave ourselves permission to get through that, it was a lot easier to wrap my hands around the idea that this is what I want: This is not second best. This is the way I want to shape my family. It just looks different than I thought it would.”

It’s not just the couple’s expectations that are in play. For the Millers, one of the hardest parts of their journey was not telling their family about what they were doing so they wouldn’t be disappointed if things didn’t work out.

Feelings of isolation are common. Kylie said she relied far too much on information from social media rather than talking about it with others.

“I basically went through this by myself,” Kylie says. “I didn’t know anybody who went through this. It’s a very taboo situation, and the more I talk about it, the more I realize that there are a lot of people out there who have gone through this. I feel like it’s better to talk about it than being secretive. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

“The best thing you can do if you’re trying to support someone going through IVF is to listen to what they have to say but don’t ask too many questions,” Melissa says.

Parsons agrees, saying: “Ask them what they need to hear from you or maybe not hear from you. Provide them a space to talk about it if they want to or provide them a space to not have to talk about it if that’s what they need.”

Amid all the emotional and physical pressure, there can also be a temptation to lay blame.

“Relationships can start to feel ‘second best’ to a potential child or their partner’s desire to become a parent. When these relationships are not nurtured properly, as in any marriage, they can start to falter,” Parsons says.

According to the National Institutes of Health, who may be infertile is divided into equal shares. In one-third of cases, it’s the man; in one-third, the woman; and in one-third, it’s either undetermined or attributed to both partners.

But more often than blame, there are feelings of helplessness watching spouses endure the process of IVF, the grief of miscarriages, the turmoil of rampant mood swings, and a resentment of the transactional nature of it all.

“It’s a lot watching Melissa going through all that,” John says. “It’s emotionally draining and even your love life feels transactional — it takes the romance out of it. The good news is that after all that, I feel like we’re in an even better place.”

“When we sat down and went through embryo adoption, it was very hard to see that the embryo was considered property,” Michelle says. “It was a transfer of property, not an adoption, according to the paperwork. It was a gut punch. Calling the embryo ‘property’ seemed very rough around the edges for me.”

Hope Springs Eternal

Jonas Salk said, “Hope lies in dreams, in imagination, and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality.”

Today, John and Melissa are parents to two daughters whose lives were made possible by IVF. Ava is four and Olivia will be two years old in February.

David and Kylie’s son, Maverick, celebrated his first birthday in November 2023. He was the first of their three embryos transferred and it was successful. They have two more embryos and plan to have another child.

In addition to Ross and Michelle’s 10-year-old son, they have a daughter — the fragile snowflake Michelle delivered eight years ago.

Perhaps the ultimate hope isn’t just bringing a child into the world. Maybe it’s overcoming incredible odds with unflinching resilience to make it happen.