Back to the Future

Reflecting on Spanish flu in the midst of COVID-19.

It’s fitting that Carolyn Orbann was immersed in research about a global pandemic when COVID-19 hit Columbia in March 2020.

Spurred by the 100-year anniversary of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, Carolyn, an associate teaching professor in the department of health sciences at MU, had been studying how Spanish Flu impacted the state of Missouri.

“I was trying to understand the flu mortality in the state by looking at all the counties to understand the geographic spread and understand why certain places were more impacted,” Carolyn says. “I was looking at what we knew about the state at that time and asking the standard questions a scientist might have about how the area was affected.”

With the help of students, Carolyn says her team searched through historical databases to learn more about how Spanish Flu affected Columbia and surrounding communities. She says she was thrilled to learn that Missouri has an incredible resource in the Missouri Digital Heritage project, something not every state has. All of the resources she’s used for her research are open and available to the public, and she says she had no special access to information.

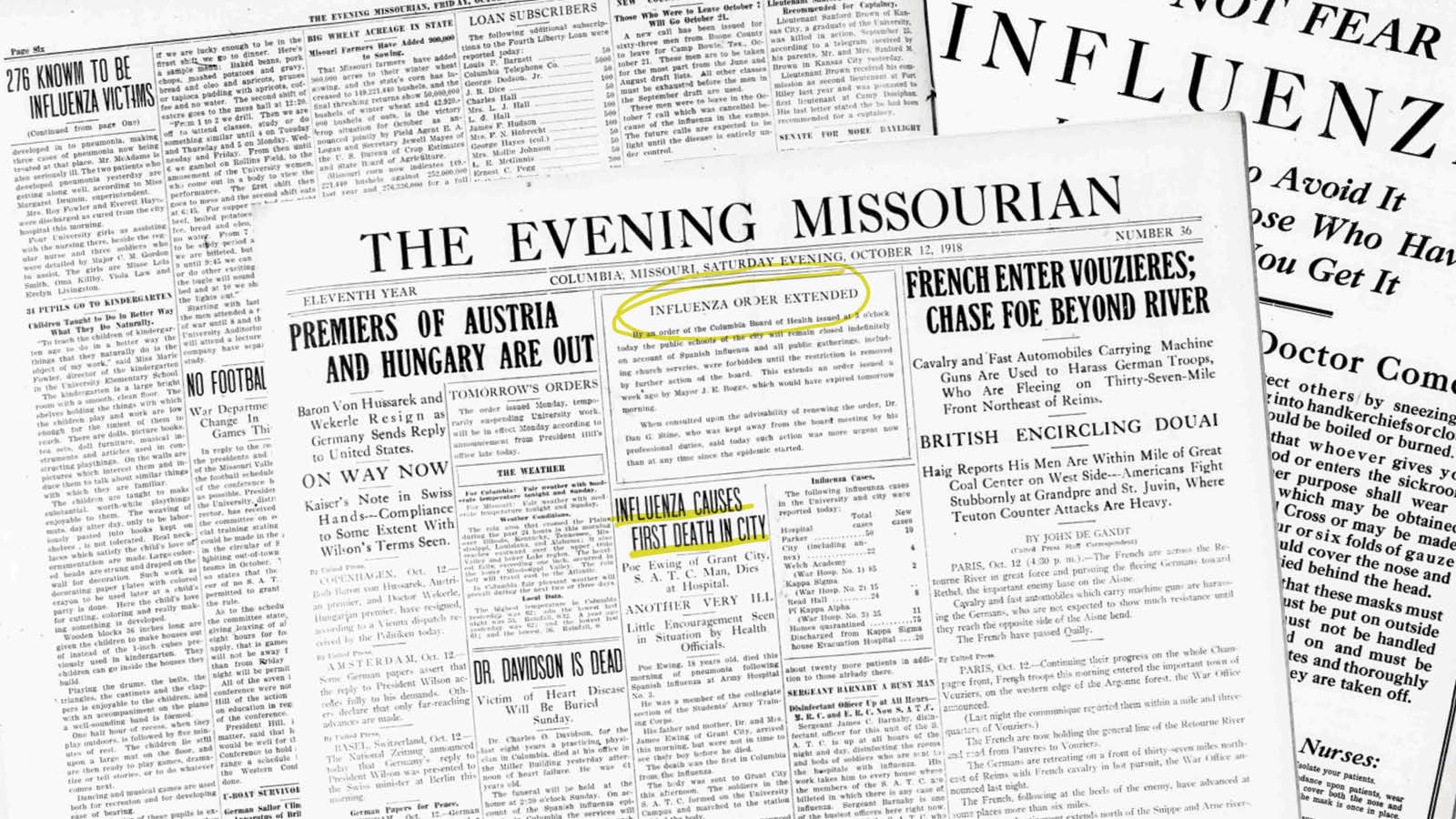

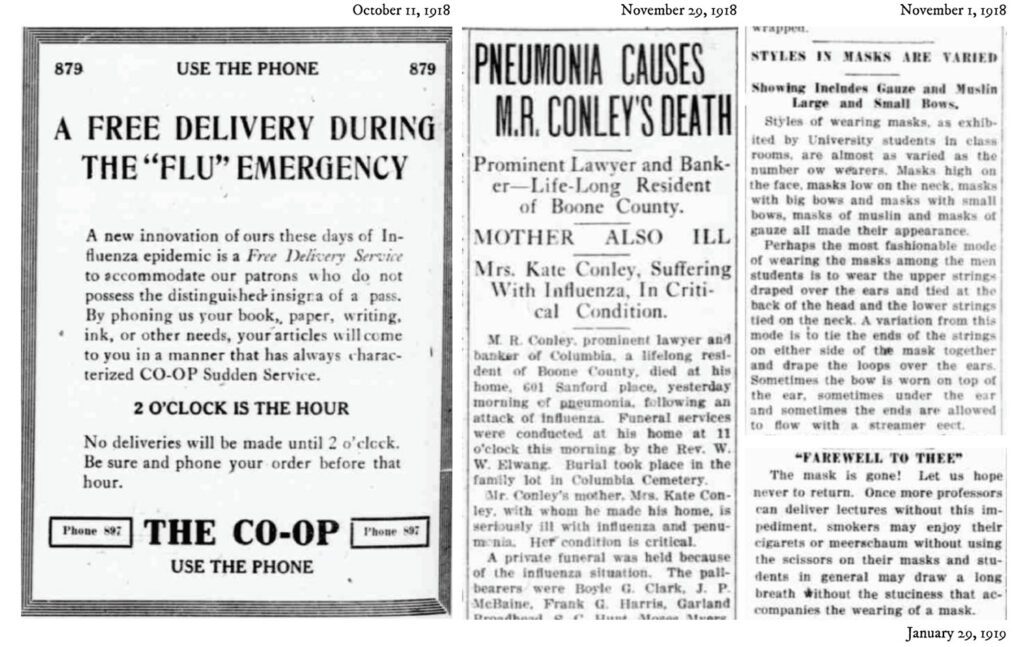

“We initially found old newspaper databases through the Missouri State Historical Society,” Carolyn says. “We have a newspaper that’s been running the entire time. It was called The Evening Missourian at the time, and it was published five or six days per week, and you can read each issue. I started doing some searches to try to see what the flu was doing here in town.”

As COVID-19 spread through the city, MU was awarded a $146,000 research grant from the National Science Foundation in May 2020. With Carolyn as the co-principal investigator of the study, a multidisciplinary team of researchers from around the university was created to compare the patterns and responses of Missouri residents during the 1918 influenza pandemic to those during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Parallels to the Past

As Carolyn and her team began combing through the archives, she says similarities between 1918 and 2020 were immediately clear.

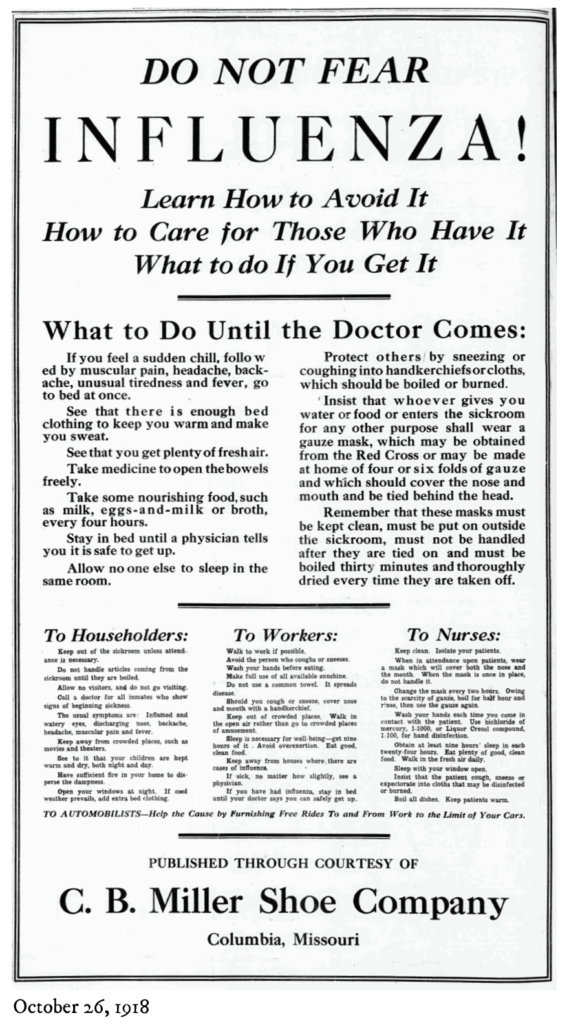

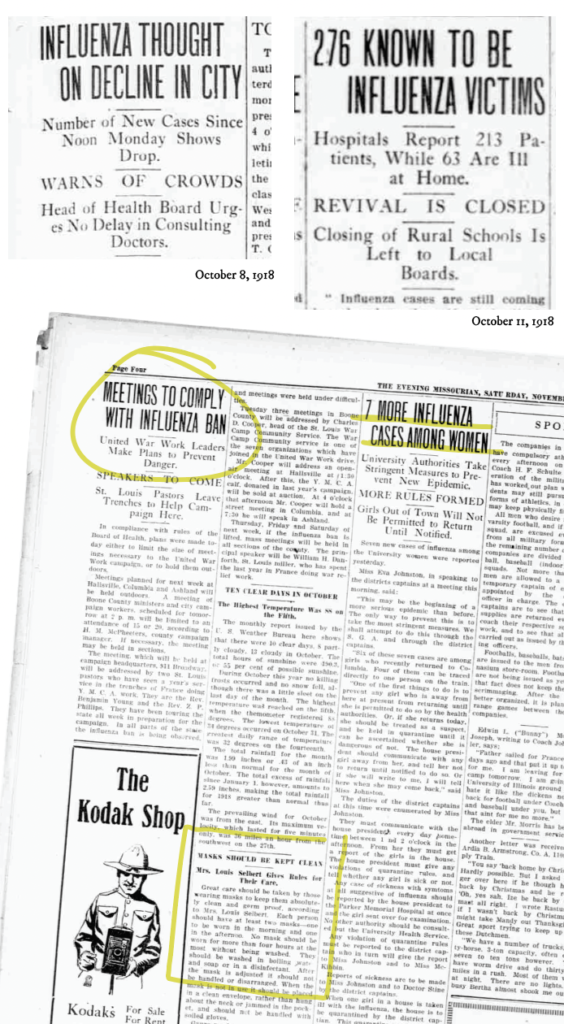

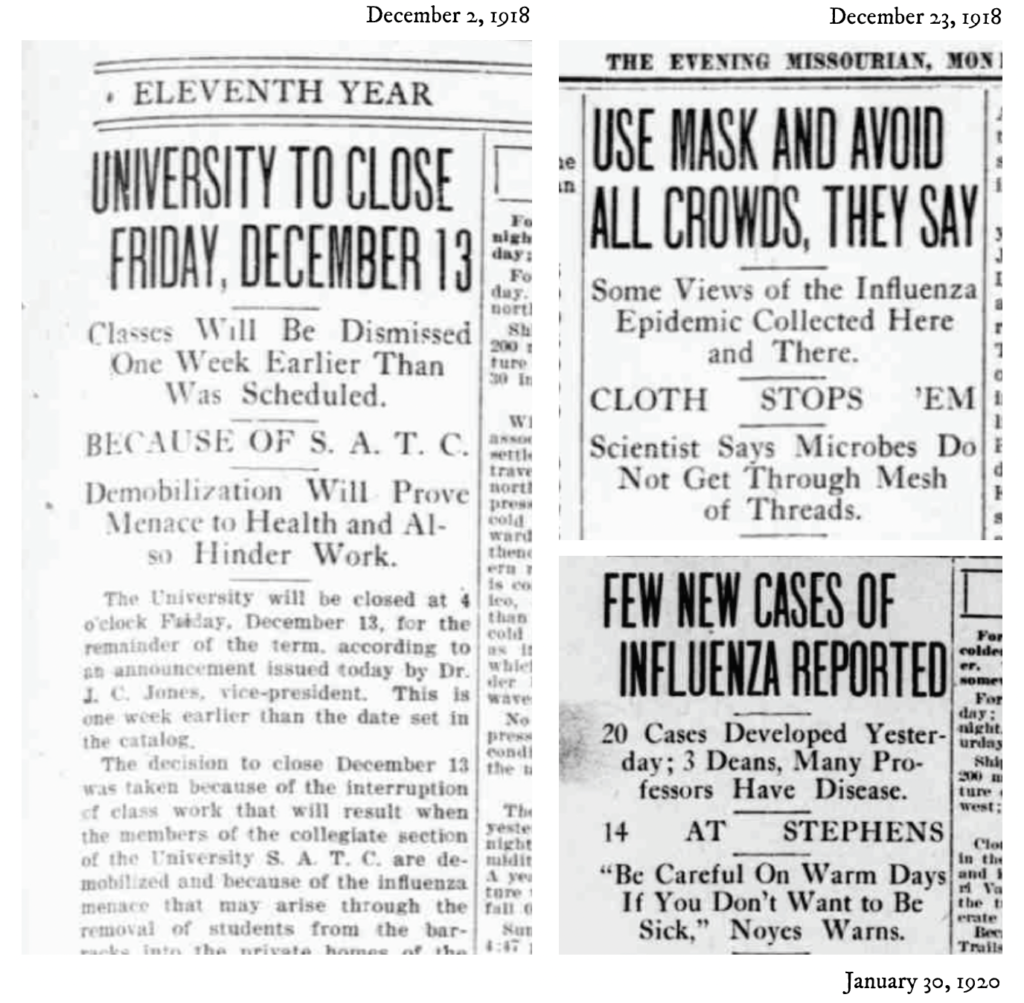

“As the COVID-19 pandemic was happening, I was doing this newspaper research with these students, and we found that the city and the university did so many of the same things as they did during 2018,” she says. “A mask mandate was in place. Schools, churches, and theaters were closed. There were occupancy restrictions for downtown businesses, and the university closed early. There were so many parallels, and it was really amazing to be able to see them through these documents.”

Carolyn’s team also studied digital versions of MU’s yearbook, The Savitar, which painted a picture of how the flu transformed daily life on campus.

“You can look through and see people wearing masks,” Carolyn says. “There was a whole section about nursing students working in the hospitals. About 1,000 students caught the flu and many people had to be hospitalized.”

“As the COVID-19 pandemic was happening, I was doing this newspaper research with these students, and we found that the city and the university did so many of the same things as they did during 2018. A mask mandate was in place. Schools, churches, and theaters were closed. There were occupancy restrictions for downtown businesses, and the university closed early. There were so many parallels, and it was really amazing to be able to see them through these documents.”

– Carolyn Orbann

A Different Time, A Different Mindset

Although most of our current population hadn’t experienced a pandemic before COVID-19, life was different in 1918. People were used to circulating infectious diseases that swept through communities, leaving countless dead or disabled.

“Back then, the mindset was different,” Carolyn says. “Measles, whooping cough, malaria, tetanus, typhoid — almost everything you have a vaccine for now, people were dying of in some numbers back then.”

And, with the way news traveled in a small town, it was impossible to escape the realities of the pandemic’s effects.

“If you look at old newspapers, you would see stuff about your neighbors, their names and addresses,” Carolyn says. “They would have sick lists, whole lists about who was sick. As the pandemic was starting to ramp up in these towns, you couldn’t help but know that people you knew were sick or dying. You could very quickly see the impact of the pandemic. Now, unless you have someone in your social circle with COVID-19, you don’t really see the impact of it firsthand.”

Embracing Science

While the scientific community’s understanding of viruses has greatly evolved since 1918, at the time, Carolyn says that doctors and scientists didn’t have a widespread understanding of viruses. Yet, when the flu vaccine became available, Carolyn says that her research shows that people were excited.

“Vaccines were new enough as an idea that people were dazzled by them, and this was a time when science seemed really exciting,” she says. “It seemed in general that people were excited and that the state board of health was excited. If there was an anti-vaccine sentiment, I wasn’t seeing it in these sources.”

Her sources also highlight the fact that 1918 was the golden age of public health, a time when new sewer systems were being built, new laws about food safety were evolving, and water quality became a focus.

“People were putting their health care investments into prevention,” Carolyn says. “Now it seems like we are all about treatment, curative care. We’ve let our budget and focus fall away from the public health aspect. Vaccines are excellent and it is great that we have clinical treatments, ventilators are amazing, and the quality of care you can get is frankly miraculous. But clinical care is not accessible to everybody, and that’s a real problem.”

A Changing Social Context

In 1918, the United States was at the end of World War I, patriotism was high, and the country was united around the war effort. Much of the discussion around the flu was related to stopping the spread of disease in order to keep soldiers healthy. Though Carolyn says that the public didn’t necessarily understand the specific pathogen that was making people sick, they understood the degree of infectiousness and they were quick to embrace mitigation efforts.

Her examination of death records reveals that there were both primary and secondary causes of death listed, and there didn’t seem to be an argument about flu being listed secondary to a primary cause of death.

“As people who study infectious disease, we know that the disease you attribute to the cause of death sometimes goes beyond that,” she says. “A lot of people who died from the flu actually died from pneumonia. Flu is a virus that can make you more susceptible to pneumonia, which makes you more susceptible to death. The primary cause of death was listed as pneumonia and the secondary cause was flu. As researchers, we can use that death in our data.”

Carolyn says that the flu can also cause heart problems or bad pregnancy outcomes, and in those cases, flu would have been listed as a secondary cause of death. Her research did not reveal any contention about what deaths count as pandemic deaths.

“That’s something I didn’t see in 1918, where people said that a death didn’t count as a flu death, and I think that is something we are seeing now,” she says.

Does History Repeat Itself?

As a researcher who builds computer models of infectious disease, Carolyn says she is still trying to understand the trajectory of the flu in 1918. Around Boone County, there was a three-wave structure, with spikes in deaths in fall and winter of 1918. After death rates slowed, a severe wave in February 1920 left even more dead than in the initial wave.

“February 1920 was a steep peak almost everywhere throughout the state, then it just went away,” Carolyn says. “It’s weird. I think that’s what people are hoping for now, but we know Omicron is a different strain and coronavirus is a different disease. Omicron seems to be a case peak, not a death peak.”

As she continues her research to try to understand why there was such a severe peak of flu in February 1920, she says she is using what’s she’s learned about COVID-19 as a frame of reference.

“I’m thinking about ways to help me interpret 1918 and I wonder: Did people get tired and go back into the world?” she says. “I have no idea. I’m still trying to understand that better.”

Though there are similarities between flu and COVID-19, Carolyn says that the nature of viruses makes predictions incredibly difficult. It’s unlikely that understanding the waves and peaks of the flu pandemic will shed light on what’s on the horizon for COVID-19.

“The historical data are interesting, but I would never predict COVID-19 based on 1918,” Carolyn says. “It’s really hard to make predictions because you have to consider the geographic distribution of people, social connections, how random chance plays a role, there is so much. I would never give a specific date. At this point, most people are comfortable saying we aren’t going to get rid of it, and I think I largely agree. We’re way past the point where we’re going to be able to put it back in the bottle.”

This story contains digital scans of The Evening Missourian newspaper. Archived issues are available in digital format as part of the Library of Congress Chronicling America online collection and are provided by the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, MO.