The Vital Vets

- Photos courtesy of The College of Veterinary Medicine, Lizette Somer, Charlie Harris, and Sarah Lacy

+2

+2 The Vital Vets

The story of the Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine and the keys to its success, even during a global pandemic.

Since being established in 1884, The University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine has become one of the most prestigious institutions of its kind. It’s one of only 30 veterinary colleges in the United States accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association. It’s also the only Missouri college to confer the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree.

The simple goal of helping animals and people has driven the college’s success over the years, making it a destination school for prospective vets. What began humbly as a single course in veterinary science in 1884 has progressed through various stages of expansion, eventually becoming a separate department and then the proper MU College of Veterinary Medicine as we know it today.

According to the school’s official history, the early era saw staff vets teaching courses to medical and agricultural students, conducting research on tick fever, and investigating livestock disease throughout the state. The first vaccine virus laboratory in the U.S. was established in 1885 at the veterinary science department, as it was known then, and two years later, the campus got its first veterinary lab.

One of the college’s first buildings was Connaway Hall, erected in the 1910-1911 year. It was constructed to house vet science faculty who were teaching courses to agriculture students. Their research included investigations on animal and poultry diseases and the development of animal vaccines.

Dr. Edna Guibor, first female graduate, 1952. (Missouri Ruralist Photographs. P0030-1743. The State Historical Society of MIssouri. Photograph Collection)

In 1946, the professional curriculum culminating with the DVM degree was put in place. It was meant to offer educational opportunities to World War II veterans, and 26 new vets (that’s veterinarians, in this case) graduated in the first class of 1950. The school’s first female vet graduated two years later. Over time, the graduating classes would get larger as the college expanded and accepted more students. From 1946 to 1965, each of the four classes studying for the DVM included 30 students — all Missouri residents. That size doubled in 1965 when non-residents were accepted following federal funding incentives meant to alleviate a national veterinarian shortage. The shortage eventually leveled off in the early 1980s, when funding was pulled. Now, the college has accepted 120 students each year since 2010, and over 4,000 vets have graduated since 1946.

The aforementioned curriculum that leads to a DVM degree is known for its unique structure meant to prepare students for the real-world scenarios they’ll experience in their future careers in veterinary medicine. For the first two years of the program, students work in state-of-the-art, computer-based classrooms and special clinics. Then they’ll experience nearly two years of hands-on training in the veterinary health center hospitals and the veterinary medical diagnostics laboratory, working in service rotations of two to eight weeks.

The numbers are a testament to the college’s commitment to its goals: Since 2010, the college has had a pass rate of 97 percent or better, graduating approximately 115 new vets each year. In the process, nearly 20,000 animals are cared for in the college’s hospitals and clinics throughout the state.

In the era of COVID-19, the veterinary world at large has been hit with increased challenges to daily work life — not to mention the strains put on higher education at universities like MU. Many first-time pet owners have also discovered the importance of the veterinary occupation, which goes far beyond just treating our pets. In her message to recent graduates, Dean Carolyn Henry (aka “Mama Hen,” as she was lovingly dubbed by a former student) was unwavering in her message of hope and persistence.

“The CVM class of 2021 will always hold a special place in my heart,” she said. “Nothing could have prepared any of us for the global pandemic 19 months into their studies and the adjustments it required to the way we taught and the way they learned. Like any mama hen, I’m proud of the way our graduates responded. Their well of resilience, grace, patience, and resourcefulness was seemingly bottomless. In overcoming the challenges they faced to finish their education without compromising their knowledge and skills they wanted to acquire, they proved they have what it takes to succeed wherever they go and in whatever career path they pursue.”

Like many colleges, the CVM shifted to online learning in 2020 while safely employing the hands-on education it’s known for. Students filled out return-to-work authorization forms to return to clinics and labs wearing face coverings, while the hospital shifted to emergency and essential-only cases.

“We will need to be creative, we will need to adjust to changes along the way, and we will need to support one another,” Henry said in her statement at the time. “But I have no doubt we can do this and emerge stronger than before.”

Thankfully, things are looking brighter. As of June 7, the veterinary health center was reopened, including lobbies and exam rooms. Students will hopefully be able to concentrate on their studies with less distraction, and there’s certainly a wide range of subjects in the DVM curriculum. The list of required core material is robust: equine medicine and surgery, food animal medicine and surgery, anesthesiology, radiology, neurology and neurosurgery, oncology, ophthalmology, small animal orthopedic surgery, small animal soft tissue surgery, diagnostic pathology, small animal community practice, small animal internal medicine, small animal emergency and critical care, and theriogenology.

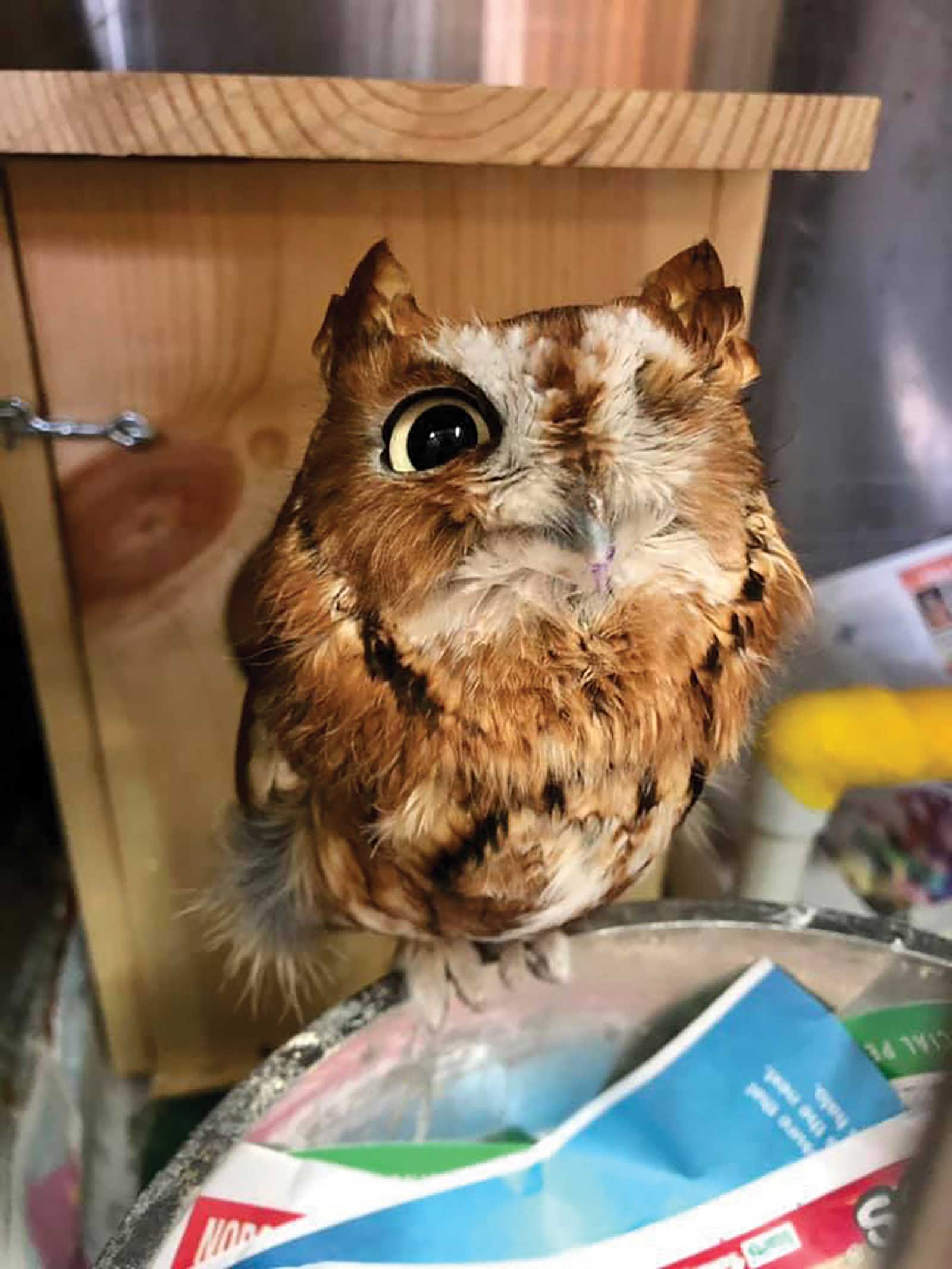

The CVM also provides alternate services that aid the local environment and its many creatures. One example is the Raptor Rehabilitation Project, which aims to release injured birds of prey back into the wild. Those who find an injured raptor (owls, eagles, hawks, etc.) are encouraged to contact the CVM. In addition to treating injured raptors, the project’s goal is to educate the public on the importance of big birds in our ecosystem.

Other notable research at the CVM includes work from the MU Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center, Mutant Rat Resource and Research Center, and the Laboratory for Infectious Disease Research — the last one is particularly important at the moment. Dedicated on the MU campus in 2008, it’s one of only 14 similar facilities in the country, housing state-of-the-art tools for studying infectious diseases such as West Nile virus and tularemia, pathogens common in Missouri. The research center can also assist in the event of a bioterrorism or infectious disease emergency — such as the current pandemic — on national, state, and local levels.

The CVM continues to grow and expand thanks to funding from the Missouri Senate and House Agriculture Committee. In 2017, $2.9 million was allocated to erect the large animal ambulatory facility. The facility includes offices, classrooms, and lower-level docking bays for ambulatory vehicles — fully stocked trucks ready to head out to the farm to treat injured animals. It’s not uncommon to pass one of the equine ambulances on a rural highway as the vets race to help an ailing horse.

“One of our initiatives as a college is to try to increase programs that will hopefully train people who are interested in practicing in rural areas, and our ambulatory program is an important component of that,” said John Middleton, professor of food animal medicine and surgery, in a press release announcing the facility in 2017.

The college remains invaluable to not only the local communities of Missouri, but to the future communities where these vets will serve later in their career. That could be in a variety of roles, whether working on the front lines in an animal hospital or under the microscope in a research lab, gaining insight on the infectious diseases that we all live with, humans and animals alike. There are currently over 95,000 vets in the US, and the number grows annually. Thanks to the CVM, there are around 115 new vets entering the workforce each year already boasting hands-on experience.

As Henry said in her speech, “Wherever our newest graduates go and whatever type of medicine they practice, I hope they look back on their days at Mizzou fondly, pandemic notwithstanding.”