How the pandemic is affecting college-town culture.

Gary Ward has a keen understanding of COVID-19 fatigue. He also has a treatment — at least temporarily — for the ubiquitous anxiety over social distancing, uncertainty, and daily case number reports that expand the pandemic’s physical and psychological footprint throughout Columbia.

Gary, the vice chancellor for operations and chief operating officer for MU, was quarantined at home with his wife the morning after Election Day. “She asked me where I keep the shovel,” Gary says with a wide grin via Zoom, proving that a self-deprecating laugh is good medicine right now.

Three months ago, though, Gary was at the center of Columbia’s pandemic picture when returning college students incubated a surge of local COVID-19 cases that spurred new occupancy and operating hours restrictions for local bars and restaurants. The surge also led to a rapid response from university leaders.

Stemming the Surge

Case numbers “went up like a rocket and fell like a rock,” Gary says, pointing to the university’s measures that clamped down on social gatherings and ratcheted up social distancing rules.

“When we saw the spike in September, there was an, ‘Oh, no,’ from all of us. We addressed that quickly,” he adds.

Combined with new health department restrictions on hours of operation and occupancy, the university’s changes — including tactics like rearranging the seating in campus dining facilities — helped bring the COVID-19 case numbers back down.

“Socialization is a big part of life, especially for our students,” Gary says. One change, for example, was to limit each table in the dining halls to one person. This shift was not popular among the young adults who live on campus, just as the COVID-19 surge wasn’t popular with the wider Columbia community.

The sudden uptick in cases was one of the first times that Matt Pitzer, city councilman for the Fifth Ward, “felt a little bit of tension” between the community and the university. He says the misgivings were from community members, not necessarily businesses, “who were just starting to feel better about getting out and about.”

But the tension didn’t last.

“I was impressed with how [the university] quickly responded with new protocols,” Matt says. “All the cases in the community declined. I think we were all feeling a lot better about the place we were [heading].”

Lights Out at 10:30

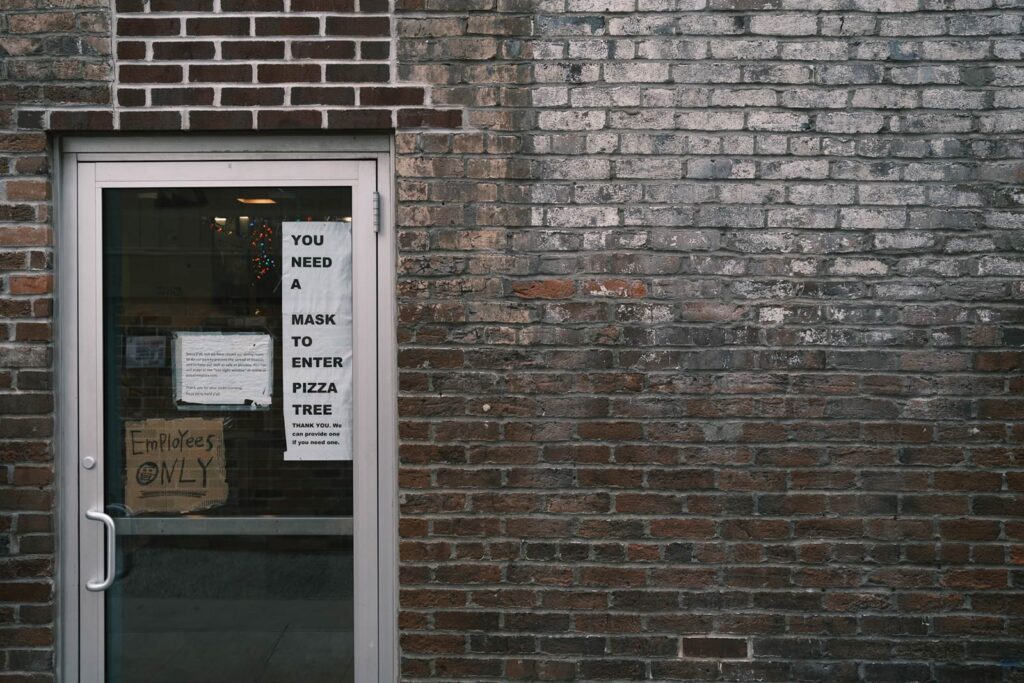

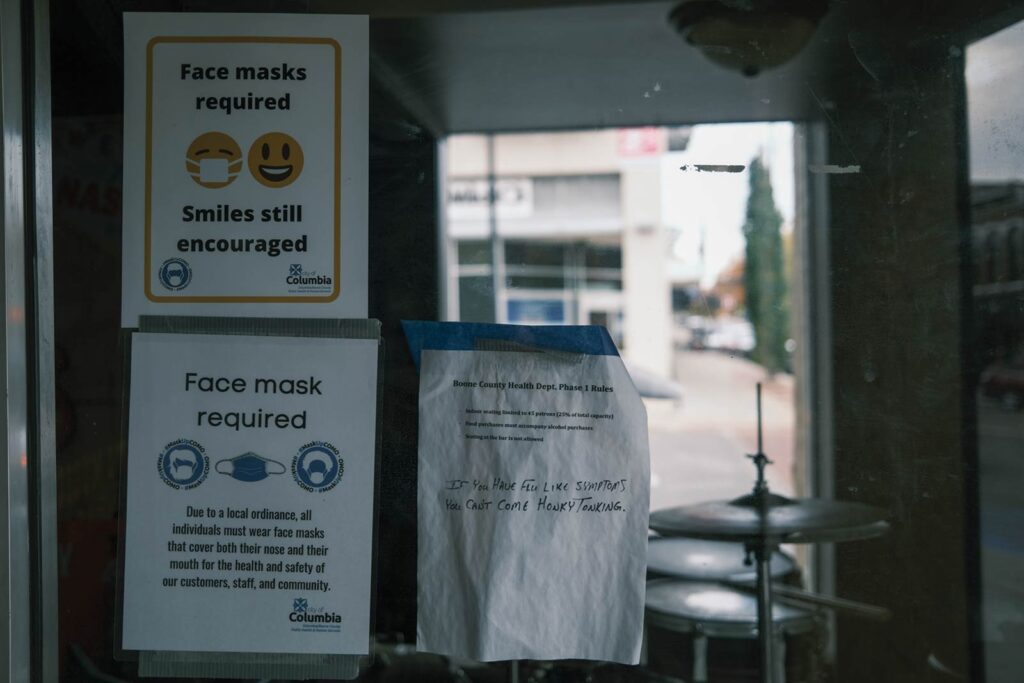

Maintaining and nurturing the community’s symbiotic relationship with its college students is daunting with social distancing rules in place. No tailgating for Saturday football games, seating limits at Memorial Stadium, and a closing time of 10:30 p.m. for bars — all these measures change the fundamental experience of Columbia for many.

But Columbia’s college-town culture extends far beyond game days, higher education, and popular gathering places. Columbia Chamber of Commerce president Matt McCormick notes that students are also an integral part of the community’s workforce and economic activity.

“Columbia isn’t Columbia without that student population,” he says. “We’re such a college-driven community.” He adds that he doesn’t detect any lingering animosity toward the college-age crowd for the September surge in COVID cases. Instead, businesses are busy evolving and adapting, “problem-solving the same issue over and over again — sometimes multiple times a day,” he says. “It has been amazing to see how our businesses have been resilient through this.”

For instance: DogMaster Distillery shifted from making alcohol to producing hand sanitizer practically overnight. Thousands of employees for companies all over the city suddenly became remote workers. Restaurants developed pick-up and curbside services that will certainly still be part of the economic ecosystem when COVID-19 finally subsides.

“We keep pivoting to new things,” says Molly Wagner, owner of Billiards on Broadway. “We learned to do curbside fast.” Savvy marketing, and the loyalty and expertise of restaurant manager Tom Weyerick, have helped.

The restaurant and its bar rely more on college sports than on college students for its customer base, Molly says. That puts Billiards in the group of businesses feeling the pinch of local health orders that restrict occupancy and hours of operation. Rather welcoming in post-football game patrons at 10:30 p.m., these businesses must be closed.

Molly, who was honored with the Restaurateur of the Year award by the Mid-Missouri chapter of the Missouri Restaurant Association, says she’s not so sure there’s still tension between the community and the seasonal, college-age crowd.

“It’s not just the college kids,” she says. “Yes, they got the rap for being super-spreaders early on, but the virus doesn’t discriminate.”

Calling an Audible

Half of the 60 employees at D. Rowe’s Restaurant and Bar are college students.

“The college kids that work for us, they’ve got rent, school — they’ve got expenses just like anybody else does,” says D. Rowe’s owner, David Rowe. “You want to hold on to them.” He’s more concerned about the long-term mental health effects of the pandemic and restrictions that limit socializing than he is about Columbia’s college-town culture, which he doesn’t think is damaged.

“I think we slid back into what we were,” David says. “Columbia has shown that to the business community. They have supported us. I do think we come back from this.”

The need for repetitive, rapid-fire decision-making isn’t unlike what’s required of a quarterback who calls a play in the huddle, gets to the line of scrimmage, and sees the defense shift. Sometimes, you have to change the play just before the snap. David says he’s been calling audibles — a new play or approach — sometimes several times a day. His wife, Meghan, has the especially challenging chore of scheduling staff, “to be sure that everybody has earning opportunity.”

A COVID-19 infection or even exposure to the virus that puts an employee in quarantine wreaks havoc on the schedule. Inadequate staffing can be the difference between serving just a few tables or closing the doors for the day — or longer.

Some of the pivots restaurants like D. Rowe’s have made will remain part of the business plan beyond the pandemic, like curbside pick-up.

“It’s been a learning process. We’ve made mistakes, we’ve messed orders up,” David says. “But 99% of our customers are gracious enough to know we’re learning on the fly.”

Having Grace

The notion of grace resonated with Matt McCormick, as did the idea that businesses and residents are all dealing with a situation that few, if any, could have anticipated.

“We’re building the airplane as we’re flying it. We’re all on the same plane,” he says. “I believe grace could go a long way because each person is coming at this from a different angle.”

The proximity of Stephens College, Columbia College, and MU in the community’s footprint, as well as the growing Moberly Area Community College presence on The Loop, is unmistakable evidence of higher education and students fueling and anchoring the local economy.

Matt Pitzer says the college-town culture and higher education presence in Columbia, alongside health care, financial services, and insurance businesses, is the main reason Columbia has thrived and overcome other troubling times through the decades. That economic engine was humming just nine months ago.

“People are just completely retooling their entire business model in the blink of an eye. They’re doing that because they need to survive,” he adds. “Government is trying to do the same thing. Nobody ever thought, in the spring, we’d be talking about shutdowns and mask ordinances.”

Bouncing Forward

For Columbia, college parents weekends are a community-wide event. A jam-packed Memorial Stadium is a boost for business and community coffers. These events, like graduations, tailgating, and theatrical and musical productions, are part of the cultural and economic fabric of Columbia. Now, the city is learning just how much they mean to the people and businesses here.

“We talk a lot in our office about how we need to look at how we bounce forward,” Matt McCormick says. That will involve taking the community’s pre-COVID strengths and creating “an even better college community.”

Gary says he is encouraged by lessons learned so far in the pandemic response. Technology allows for distance learning and campus- or system-wide meetings without quarantining. And the sanitizing equipment and methods used to clean classrooms between classes also “work great for flu and colds,” he adds.

“There are some efficiencies that have been gained through this whole thing,” Gary says. “We had no playbook for this. No one did. We have one now.”

Meanwhile, the local restaurant industry continues to call new plays and make new pivots. Supply chain disruption is one of the wild cards of business, David says, comparing the availability of food handling gloves in the restaurant industry to the race for toilet paper among the general public in the spring.

Molly says a case of gloves went from $39 to $140 – and a pound of ground beef vaulted from $2.06 to $6.36. That was one reason Billiards added pulled pork to the menu alongside Molly’s signature ’Bout Died Fries.

Future pivots are certainly on the table, especially since there’s no end date on COVID restrictions and the virus’s ubiquitous presence. Creating local supply chains where possible and fostering a deeper sense of collaboration among restaurateurs will be key for what life and business look like post-COVID.

Billiards was just two weeks away from marking its eighth anniversary when the pandemic arrived in Columbia in March.

“I’m weary. And heartbroken,” Molly says. “We’re paying our bills. And we’re keeping 27 employed. But we’ll come back. Billiards will make it to the other side.”