Speaking from the Heart

Pediatric cancer survivor Zoe Wagner becomes a voice for the voiceless.

photos by Keith Borgmeyer

Zoe pictured above with her father, Paul Wagner, and her mother, Amy Enderle

As a toddler, Zoe Wagner had no problem with the English language. She talked “early and often,” according to her parents. She even went through a stream-of-consciousness phase while discovering sentence structure, periodically erupting into cute, spontaneous monologues.

“She would speak practically every thought that entered her mind,” says her mother, Amy Enderle. “You could almost see the little synapses firing. Someone would say, ‘Look at that pretty sky,’ and she would say, ‘Sky is blue. Dad’s car is blue. Blue car in shop. Maybe blue car needs new car.’”

But as naturally as speech came to young Zoe, it would take an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) diagnosis more than a decade later, six months of chemotherapy, and a triumphant recovery before she truly found her voice.

Now a sophomore political science major at MU and five years cancer free, Zoe is an inspiration for childhood cancer patients and a fierce advocate for research funding.

“When I first got sick, I kept wondering, ‘Why did this happen to me?’ Zoe says. “Now I’m just grateful for the medicine that saved me.”

Strange Red Dots

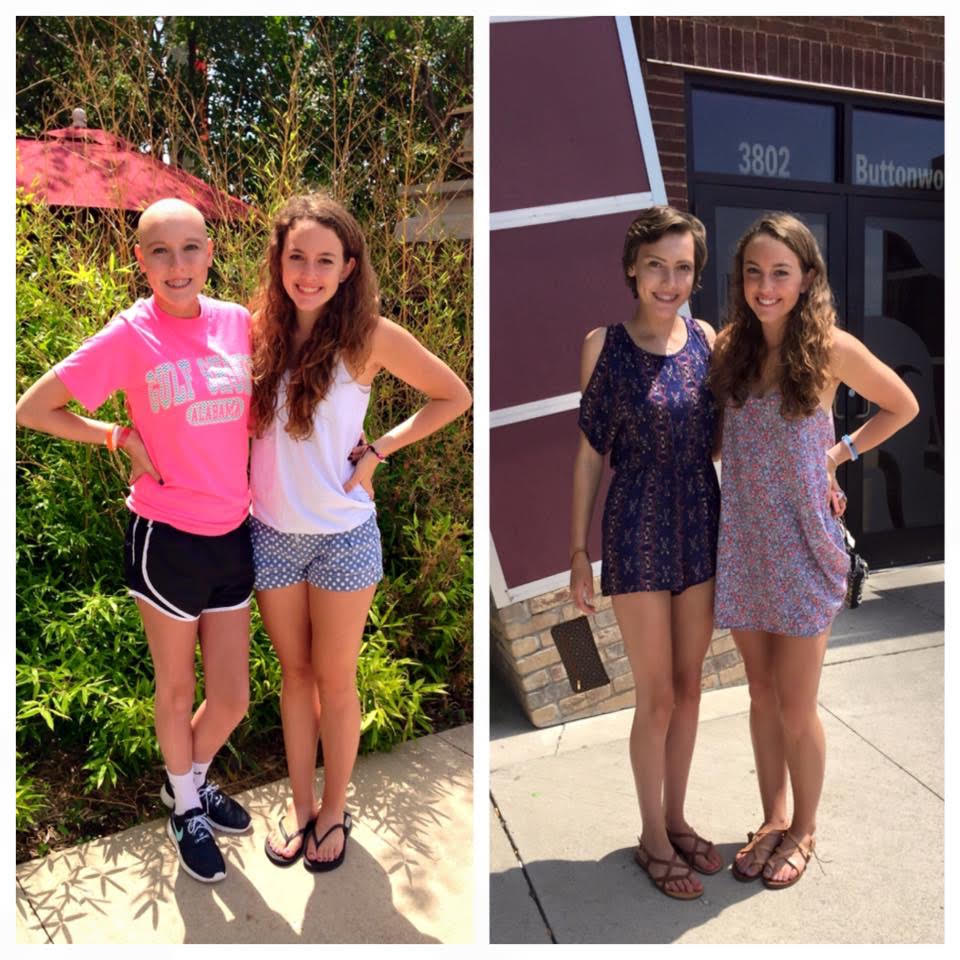

For Zoe, the term “circle of friends” might be geometrically limiting; “social sphere” is probably more accurate. As a student at Grant Elementary School, she befriended a diverse cohort of classmates, many of whom were children of international researchers and faculty at Columbia’s colleges. In junior high, Zoe and best friend, Gracie Hollrah (pictured with Zoe below), were charter members of “lunch bunch,” a group of tight-knit friends who shared snacks every other Friday.

“Zoe will always speak her mind no matter what,” says Gracie, who was also Zoe’s roommate during their first year at MU. “Because of her strong personality, she’s always there for her friends.”

Zoe would often invite a buddy to tag along on family functions, such as her brother Tycho’s April 2014 soccer tournament in Springfield. It was there that she first noticed tiny red dots around her ankles. The dots, she would come to find out, are known as petechiae, and they indicate collapsed blood vessels due to a platelet deficiency.

“They didn’t hurt. They just looked strange,” Zoe says. “I showed my mom and she said, ‘We’ve been in the grass all weekend and you might have a rash. Or maybe it’s from the detergent at the hotel.’”

Zoe wasn’t panicked, but other ailments like severe headaches, extreme fatigue, and deep bruises from mild bumps, combined with the “rash,” ultimately led the family to the doctor’s office for blood tests. Later that same night, Amy took the life-changing phone call.

“They said, ‘We need you to go straight to MU Women’s and Children’s Hospital where the pediatric oncologist is awaiting your arrival.’” Amy says. “So then it became real.”

Zoe was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia , or AML, one of the two most common leukemias (the other being the more treatable acute lymphocytic leukemia, or ALL). AML is a blood cancer that begins in the bone marrow and attacks blood cell production. For a 14-year-old girl with Zoe’s genetic profile undergoing aggressive chemotherapy, the five-year survival rate was about 29 percent.

“The nature of her illness was such that once they had the diagnosis, they had to begin treatment immediately,” says Paul Wagner, Zoe’s father. “My nature is to be logical and deliberate and to try to think things through. But emotions are overwhelming, and you’re getting a torrent of information.”

Zoe’s parents, who divorced in 2012, signed off on the treatment. Although the teenager understood the gravity of her situation, she was still concerned with teenage things, such as attending Gracie’s sleepover birthday party that Saturday. Despite the fact that Zoe felt great at the moment, thanks to blood transfusions, the doctors said no. A heartbroken Zoe delivered all the bad news on her best friend’s voicemail.

“You never think you’re going to hear that one your friends has cancer. So we decided to take the party to her,” says Gracie, who brought posters, party favors, and friends to the hospital. “We would just bring her as much stuff as we could (during treatment) so she didn’t feel alone all the time.”

In that spirit, Paul would sleep in Zoe’s hospital room when the chemo side effects were at their worst — or when she just needed her dad. At 6 feet, 7 inches, folding himself into a tiny hospital cot wasn’t the most comfortable proposition for Paul. But the experience solidified a tight father–daughter bond that is still strong today.

“Zoe really understood that, for as unfortunate as she was, she was more fortunate than a lot of others in the hospital,” Paul says. “There were children whose parents couldn’t be there, and those who had to spend extended periods of time away from their families. Even though these were terrible circumstances, there were always others who had it worse. It really put a fire in her belly to help other kids.”

No Dry Eyes

Zoe’s final chemotherapy treatment coursed through her veins on August 19, 2014. Although she wasn’t declared cancer free until that October, she considers it her victory date.

Almost immediately, she felt compelled to act. Through her constant research and activity on social media, she discovered “The Truth 365,” a documentary film and social media campaign in support of children fighting cancer. The producers told her story, and St. Baldrick’s Foundation, a childhood cancer organization dedicated specifically to research funding, soon followed suit.

The experience set Zoe on a path of activism. She met new friends and fellow cancer survivors across the U.S., sat for an interview with local radio host Tom Bradley, and traveled to Washington, D.C., for the annual cancer event CureFest. It was there that she met the Santhuff family, from Fulton, Missouri, whose son, Sam, died at age 6 from a rare form of muscle cancer. Zoe agreed to speak at the fundraising gala for the Super Sam Foundation, the Santhuff’s nonprofit dedicated to fulfilling Sam’s wish to “help all the kids.”

“Seeing her speak in front of 300 people, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house,” says Amy, herself tearing up. “She is articulate in a way that no one will ever be able to touch. I don’t know whether that turns into a career, but boy has it been a gift that she has put into good use.”

Zoe’s story also prompted the Make-A-Wish Foundation to send her, Amy, and Paul to the headquarters of Harper’s Bazaar in New York. Zoe modeled top designer fashions in a whirlwind, spare-no-expense photo shoot where she was pampered by international makeup artists, photographers, and fashion editors.

“The hair stylist had done Nicki Minaj’s hair for a music video the week before, and he does Kim Kardashian’s hair for award shows,” says Zoe, beaming. “But it was also cool because, with my parents being divorced, when else am I going to get to go on vacation with just them and me?”

Now, with more than 20 speaking engagements under her belt, Zoe’s voice is clearer and more confident than ever. She stays active with her sorority, Delta Delta Delta, and its charity of choice, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. She has met hundreds of other survivors, patients, and parents. As she looks forward to graduating — and possibly law school — she vows to incorporate cancer research advocacy into her career.

“The National Cancer Institute only allocates four percent of its budget to childhood cancers, and the small charities have to pick up the slack,” Zoe says. “I have a new appreciation for research, researchers, and the people trying to get clinical trials through. I have a better understanding of philanthropy.”