A Little Spark: The Ripple Effect of Microlending

Small business loan counselor Liza Zimmerman says Columbia is “ripe” with opportunities for microloans, socially-conscious small loans that are a building block for many entrepreneurs. Zimmerman is a loan counselor at Justine Petersen, a St. Louis-based company that provides small loans to low- and middle-income entrepreneurs through a partnership with the Small Business Administration. Companies like Justine Petersen receive large loans from the SBA and break them down into microloans, which are then redistributed to small business owners who would otherwise be pressed to find funding.

Microloans range between a few hundred dollars and $50,000. They’re available through a variety of establishments — the federal government, nonprofits, and banks all offer microloan programs. They’re popular for people starting online businesses, which don’t require very much capital, or riskier startups that can’t find traditional bank funding. Business owners who don’t have a high enough credit score to qualify for a traditional bank loan may also look to a microloan as a starting point. And Columbia, with a vibrant supply of entrepreneurs and a tight-knit startup community, is an ideal place for these loans to take hold.

Getting the Loan

Most microloan programs have a community-minded goal, seeing small business growth as a net benefit for cities as a whole; by growing small businesses and guiding business owners through their repayment plan, lenders can have a positive ripple effect. In Columbia, microloans have provided seed money to get plenty of businesses started, and Zimmerman doesn’t see the trend slowing anytime soon.

“In our world, sometimes cities will become hotbeds,” she says. “It just clicks for that city, the importance of small business development and credit — a good credit score can actually revitalize a community, not just an individual. And Columbia is at that point.”

Justine Petersen is one of three participating microloan intermediaries for the SBA in Missouri. (Enterpise Development Corporation, based in Columbia, is another.) It’s part of a program started by Congress in 1992 to help women, low-income, veteran, and minority entrepreneurs start businesses. The federal program has authorized lending partners in every state.

In 2016, Justine Petersen loaned $13 million through 1,361 loans. The national average microloan is $13,849 and has an interest rate of 7.5 percent, according to the SBA.

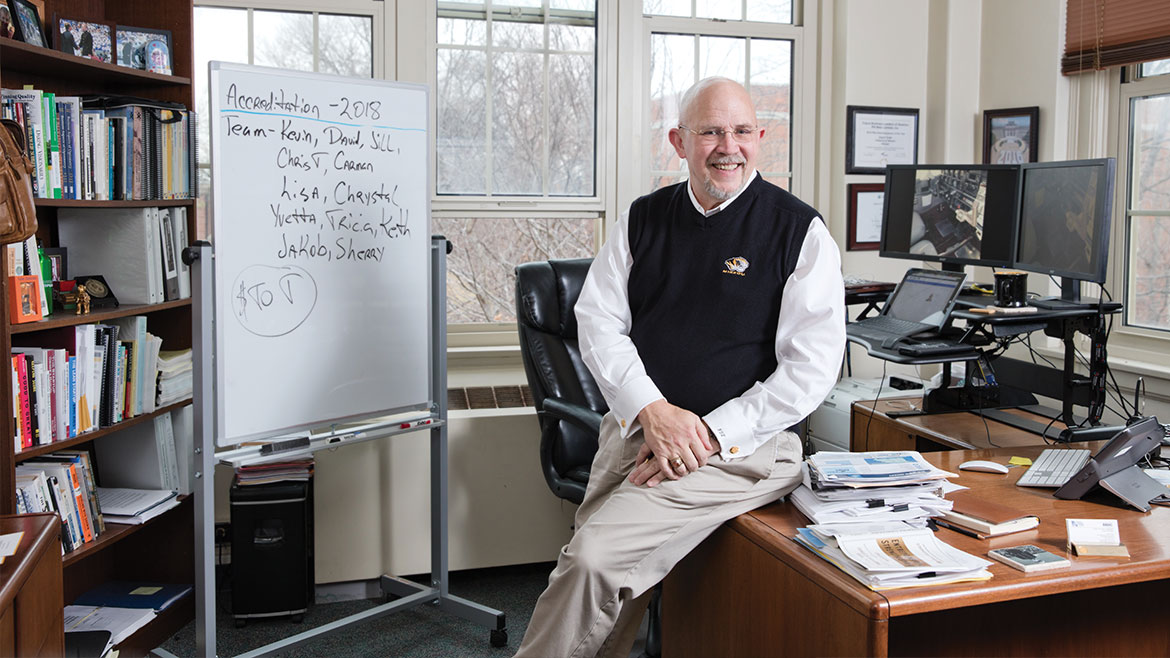

When entrepreneurs with a low credit score visit the Missouri Small Business and Technology Development Centers, or SBTDC, its director, Greg Tucker, tells them about microloans.

“Microloans are for lower amounts, so there’s less risk, as a rule, and often less credit-worthiness required of the applicant,” he says. “It’s a good way to establish business credit or, if someone doesn’t have the particular funds to open a business, it’s often a way to provide funds for that.”

Without the strong credit score, how do microlending programs determine who should get a loan? Tucker says that first the bank or other lending institution wants to see that the entrepreneur has already put his or her own time, money, and effort into the business.

Most microloan programs also require a business plan. Tucker says that for many entrepreneurs, a microloan is their first business loan. As such, it also may be the first time they’ve drawn up a business plan. That’s why microlending institutions are a little more understanding and a little more willing to help entrepreneurs along the way.

“The microloans tend to be, at least in my experience, a little more personal,” Tucker says. “In other words, that lender is going to work a little closer with that borrower because of some of the challenges a new entrepreneur might go through.”

Even though the risk is greater and the interest rate may be higher on microloans, Tucker says the default rate for microloans is about the same as the default rate for other types of loans.

“Many of the larger banks may not be interested in the smaller loan amounts because [for a larger lender] a $25,000 loan basically takes the same due diligence and application process and work as does a $5 million loan,” Tucker says. “A lot of them just don’t want to play in that space.”

Different Approaches

Microloan programs vary from lender to lender. The Bank of Missouri, for example, is a preferred Small Business Administration lender, allowing them to bypass some of the red tape usually associated with SBA loans; they have a dedicated SBA department to take full advantage. “With conventional loans, capital is key,” says Karin Bell, senior vice president and SBA program manager at the bank. “With an SBA loan, we look at cash flow of businesses as well as collateral, but a lack of collateral doesn’t prohibit us from doing the loan.”

Some banks have specialized programs for smaller loans, like The Callaway Bank’s Youth Entrepreneur Program. The program funds high school students’ small business projects by loaning them $1,000, the banks lowest available loan amount. Students have one year to pay back the loan with a low interest rate.

The program started in 2014 when a teenage boy came into The Callaway Bank with his grandmother. He wanted to raise a goat for his FFA project but didn’t have the money to buy feed and a pen, so he asked a Callaway lender for an $85 loan, says The Callaway Bank’s marketing director, Debbie LaRue.

The lender knew there wasn’t a program in place to help the young man, but he saw an opportunity. He told The Callaway Bank’s president and CEO Kim Barnes about the teen’s request. Barnes set aside $50,000 to start a program that helped young people reach their entrepreneurial goals, and the Youth Entrepreneur Program was born.

The program makes it as easy as possible for students to receive a loan while giving young entrepreneurs exposure to the business world without overwhelming them: the students do have to fill out a loan application, for instance, but it’s less than half a page.

To qualify for a loan, students must have a business plan and are encouraged to work with a school advisor.

“It doesn’t have to be a multi-page business plan,” LaRue says. “They just have to sit down with us, give us an idea of what their entrepreneurial idea is, and how they plan to make money. We just want to help them to be successful.”

Students have applied for funding for a variety of projects, but LaRue says farm animals for 4-H and FFA projects are the most common. In some instances, students used the loan to upgrade their equipment: a Columbia-area cupcake baker bought an industrial mixer, and a burgeoning photographer bought a new camera.

“If we can reach these kids earlier on and teach them financial responsibility, they’re going to be in a much better place as they become young adults,” LaRue says.

In other words, they’re betting that many small investments can create successful companies that contribute to a healthy community — that’s the essential argument for microloan programs. And in Columbia, the opportunities keep knocking.