Clary-Shy Agriculture Park: Accessible Ag for All

- illustrations courtesy of Friends of the Farm

The Boone County Fair has moved around a lot in the 182 years since its inaugural celebration. Fairgrounds of yore have been casualties of urbanization, gradually nudged further and further out of Columbia and into rural Boone County as the city has gotten denser. The fair moved to its current home, Sturgeon, in 2016, after spending two and half decades or so at the Central Missouri Events Center, just north of Columbia city limits. The last fairgrounds inside the city were on West Ash Street at a site currently split between the ARC and Clary-Shy Park, a patch of city-owned land that only got a name in 2010, 15 years after Ron and Vicki Shy gave it to them. You can still find two echoes of the Boone County Fair, and its celebration of area agriculture, at Clary-Shy Park. One is a shin-high plaque marking the burial site of Stonewall King, an American Saddlebred stallion who was honored at the fair in 1947, two years before his death, and awarded a key to the city. (No city officials could recall or find evidence of this honor being bestowed on a human for at least the past 20 years.) The other is the Columbia Farmers Market.

The market was first organized at the fairgrounds in 1980 — a way to keep fresh Boone County produce in the city for the 50 weeks a year when there wasn’t a fair going on. Vendors set up under a pavilion provided by a local Kiwanis Club for a while, but in 1992, when the fair moved after 43 years, the pavilion went with it. Since then, the farmers market has occupied an unsheltered asphalt pad at the park every Saturday (except in the winter, when they move inside the Parkade Center on Business Loop). There aren’t any bathrooms. If you want to sit, there’s a decent-sized boulder nearby, but that’s about it.

“We want a farmers market that’s a destination,” says Gabe Huffington, the city’s park services manager. “So if you live on the outskirts of town, whether that’s in Centralia or Hallsville or wherever, you can say, ‘Hey, today, I want to go the farmers market.’ Right now, you get in there, buy your fruits and vegetables, and you leave. We said, ‘Hey, let’s make it an event to go to the farmers market every Saturday.’”

The city’s parks and recreation department represents one partner in Friends of the Farm, a coalition that’s come together to create a destination “agriculture park” at the site of the former fairgrounds. Once completed, it will provide a permanent, sheltered home for the farmers market, as well as a permanent home for the Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture, another Friends of the Farm partner. Organizers think it will help Columbia reclaim something it’s lost over the past couple generations: a meaningful connection to food and the process of growing it.

Making the Space a Reality

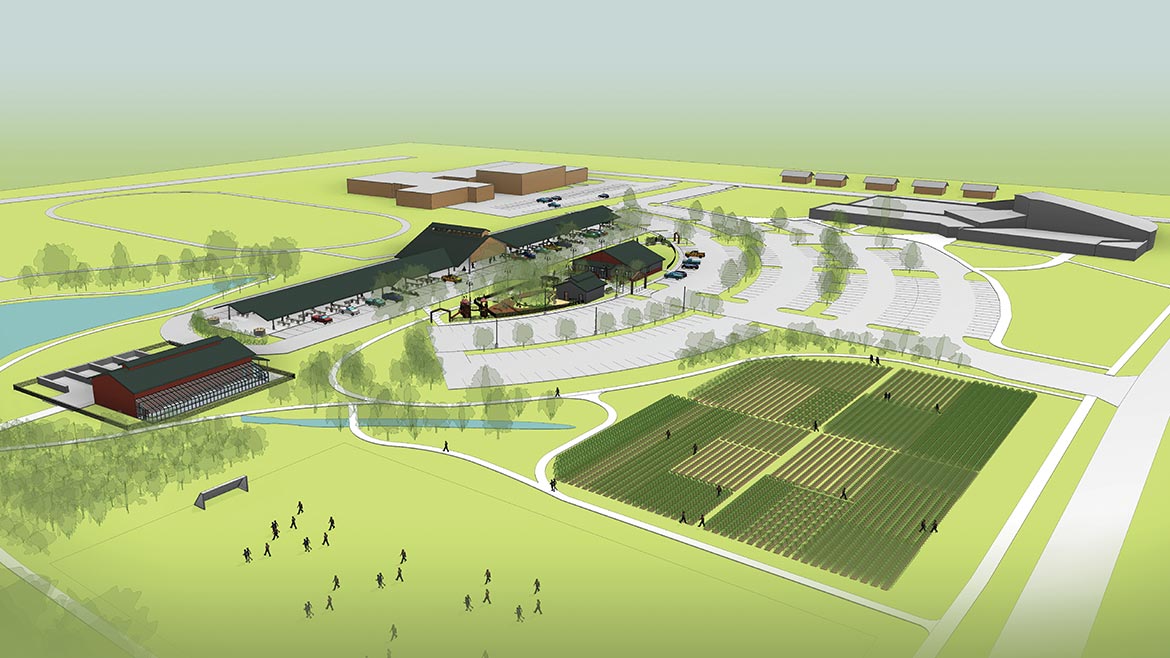

The agriculture park is going to look like this: a 37,800-square-foot roofed home for the farmer’s market, complete with room for 100 vendors, bathrooms, overhead fans, and, in the winter, drop-down walls; a four-acre urban farm, where CCUA will host their educational programming and grow food to be donated to the Food Bank; a 2,500-square-foot office building to be used by CCUA, the Columbia Farmers Market, and Sustainable Farms and Communities, a sister organization to the farmers market and Friends of the Farm member; an “outdoor classroom” where CCUA will host demonstrations and teach children about agriculture practices; a playground, adjacent to the classroom; lots of seating options; a walking trail lined with food-producing plants, like apple trees or blueberry bushes; a community orchard; a barn and greenhouse; soccer fields; a 1,200-square-foot multi-purpose building for the Department of Parks and Recreation; a teaching kitchen; 32,000 square feet of added parking; and a lake for stormwater management.

It’s going to take about $5 million. As of this reporting, about eight months into the fundraising process, Friends of the Farm has raised about $2.5 million, according to Adam Saunders, the campaign director and CCUA’s development director.

“It’s been a little bit quicker than we were expecting,” Saunders says. “This is the first capital campaign I’ve been involved in, so it’s been a learning experience, but we’ve got a great project. It’s not hard to get people excited about it.”

The $2.5 million is enough to break ground on phase one of the project, with the first priority being the new farmers market area — which, thanks to a $495,000 donation, will be named the MU Health Care Pavilion. Construction will be done in three phases; Friends of the Farm hope to have the park finished by 2021.

The city has tried in vain to put something in Clary-Shy park since the late ’90s, but, with the exception of the ARC, nothing has worked out. Sustainable Farms and Communities had plans drawn up for an expanded farmers market facility at the site as early as 2001, and in 2005, the city put out a park sales tax ballot issue that would have built a multi-use facility with an ice rink, indoor sports complex, and covered market at the site. It was defeated by a 12-point margin. In 2008, the city even approved a plan in which Sustainable Farms and Communities would raise $900,000 for the city to build a new shelter, but the funding fell short. (A concurrent project, to build a youth basketball facility at the site, was also abandoned.)

The pieces didn’t fall into place for the agriculture park until the run-up to the 2015 park sales tax renewal, when the farmers market and Sustainable Farms and Communities came to the city with a new fundraising partner: CCUA. The organization was looking for a larger and more permanent home than their one-acre plot off College Avenue, which they currently borrow from developer Mark Stevenson in exchange for eggs and tomatoes. With CCUA involved, the project began to look more ambitious than merely constructing a market shelter — the Clary-Shy Agriculture Park, as the group started calling it, could be a destination. The ballot issue, which included $400,000 for the agriculture park, passed.

“We always talk about improving quality of life for our communities, and when you look at Kansas City or Springfield, you see all these people coming out and going to the market,” Huffington says. “That was really the one thing — we know we have a market, but how can we make it better? And we took it upon ourselves in the parks department to foster that along, and we knew if we could put some money into it from the park sales tax and get people talking about it, it could be successful.”

All fundraising operations have run through Saunders, the “point person,” as Huffington calls him. Saunders says they’ve taken a “diverse sector” approach to the project, recruiting people in different business sectors — education, banking, health care, etc. — and using them as de facto ambassadors, facilitating meetings and making introductions. “A big part of this is peer-to-peer networking, having people around town who can say ‘Hey, this is something that might be of interest to you,’” Saunders says.

Plus, the park makes a pretty easy sell, Saunders says. “We all eat, right? So we all benefit from eating healthy foods. The agriculture park is a venue to support healthy living in this region.”

The Rural-Urban Connection

America’s urbanization patterns have been slowly grinding against rural, agricultural towns for more than a century — the 50-mile radius of Columbia that the Columbia Farmers Market pulls its vendors from offers a clear example. One hundred years ago, Columbia fit in much better among Mid-Missouri farming towns than it does today — in 1920, for example, Columbia’s population was about 10,000, compared to Centralia’s 2,000 and Boonville’s 4,000. Columbia’s economy grew less dependent on agriculture — the city urbanized and the population grew. But rural Mid-Missouri towns stayed about the same size — Centralia’s population is still under 5,000, and Boonville’s population is still under 10,000.

Until the second half of the last century, even, you didn’t have to venture very far out of downtown before you ran into farm country, which is why the Boone County Fair was held somewhere we now consider the central city. “Locally grown food” has taken on a much different connotation in Columbia — something special, something you have to make an effort to find and eat — than it’s meant for most of the city’s history.

The agriculture park, its organizers hope, will provide a backchannel to that history — a way to navigate the urban-rural chasm that’s getting wider with every generation.

“It’s a heritage thing,” says Billy Polansky, CCUA’s executive director. “It’s not necessarily like a new, cool, hip thing. It can be, if that’s what you want it to be, but it’s also like, this is what people did for generations, and it’s sort of gotten lost. Our approach isn’t to shove anything down people’s throats — it’s to give people the opportunity to be a part of that. . . . So many kids come out here and they’re like ‘Carrots grow in the ground?! Eggs come from where? Oh my god!’”

The agriculture park, with its many stakeholders, will offer a chance to not only build relationships with people who are growing and selling food nearby, but also to learn about exactly what it takes to grow and sell food — and maybe earn the farming industry some urban converts.

“If we want to have more successful rural areas and farming communities, they need to have more people,” Saunders says. “And those people need to come from somewhere, and some of those people are going to come from urban communities.”

The agriculture park’s creation of a stable, reliable outlet for farmers to sell food will go a long way toward creating a stable, reliable community of farmers for city-dwellers to connect with. The Columbia Farmers Market has stayed committed to hosting only vendors within a 50-mile radius of the city, meaning they have something invested in Columbia’s success and vice versa — it’s an ethos for the market that will carry over into the agriculture park.

“Everyone is really producing what they sell, and I think that’s a major philosophy that’s going to stay in place at the farmers market,” says Dustin Stanton, a campaign committee member and farmers market vendor. He and his brother, Austin, own Stanton Brothers Eggs, the largest free-range egg business in the nation. (Both Stantons, by the way, are under 25.) “The unique thing about that is that all the money goes back into the communities that are struggling.”

Columbia Farmers Market vendors have long struggled with low turnout in bad weather, not to mention the steep attendance drop-off when the market moves inside Parkade Center in the winter. And if the market is slow, farmers don’t always have a good backup option — depending on the shelf life of their produce, there can be a lot of waste. Having a protected, year-round place for both existing and new vendors to sell will fortify a market that was already drawing good crowds when it was just a row of tents on an asphalt pad. There will be places to sit, and an area to occupy kids while adults shop, and be a centrally-located source of produce for low-income families, who might also talk to someone who can teach them how to plant their own produce at their own home. (The farmers market already accepts SNAP and WIC payments for food, and they match SNAP purchases up to $25.) And that’s not mentioning the fact that the urban farm, where CCUA harvested 14,651 pounds of produce last year, mostly to give away to the Food Bank, will be four times bigger.

Nothing New

When I talked with Polansky, we were walking around the current urban farm — there was a vacation bible school group working there that day as well as a group from Camp Salsa, a program CCUA runs with the MU Family Impact center. The one-acre site is as full as you could imagine it being — we walked through narrow pathways between leafy bushes and rows of soil and shade tents. Polansky says they use “pretty much every square inch of tillable space.”

The agriculture park will fulfill a long-sought goal for the farmers market, and the city will finally get good use out of Clary-Shy Park, but CCUA will undergo the most transformative change among the Friends of the Farm. The $2.5 million raised for the park so far is more than CCUA has raised since their founding in 2009. They’ve built their organization through striking partnerships, whether with MU or Columbia Public Schools or local churches or nonprofits or whoever else might be interested in urban agriculture but doesn’t want to maintain a farm in the middle of the city. So it’s fitting that their largest growth spurt is coming through a broad public-private partnership. “I guess you could say we play well with others,” Polansky says.

We’re walking through the blackberry bushes, which are a little taller than I am, and about half a head taller than Polansky is. He’s talking about how they’ve been able to coordinate the efforts of three nonprofits and a city government department without derailing. “Each party brings to the table their own unique thing,” he says. “We’re each bringing — let’s see if there are any ripe blackberries.” He pauses, brushes leaves away, digs deeper into the bush. “They’ve been picked over pretty heavily.” He grabs one, brushes it off with a finger, and pops it in his mouth. “Would you like one?”

I would. He hands me one and I brush it off with a finger and pop it in my mouth, like I do this all the time. I’m no fan of blackberries, but it was good. And I’m so taken aback by the fact that I’d just eaten something that was attached to a plant ten seconds ago that I almost miss Polansky getting back on subject.

“So, yeah, we’re each bringing a unique skill to this partnership,” he says. “And, again, it’s the partnership that’s going to make this project so successful. There’s no duplication of efforts.”

We walk back to his office, across the street from the farm, and he circles back to a question I’d asked. “So you asked, ‘Can Columbia handle this, is this right for Columbia?’” he says. “In a lot of ways, none of this is new. Farmers market has been here for 20 years. CCUA has been here, teaching kids, growing food. City parks has been running parks. It’s not — there are some new components, but we’re just taking these tried and true things and putting them together.”