Real Estate Shortage: What’s Your Plan B?

Imagine you’re a first-time homebuyer seeking a starter home in Columbia. Maybe you’ve just graduated from college. Maybe you’ve been living with relatives for a few years to pool your resources before finally branching out on your own. Maybe you’d been enjoying the single life in an apartment, but now you’re ready to settle down and start a family.

In any case, you’re not a millionaire. You make enough to get by, but you can’t afford a luxury house.

Columbia only has around two months’ supply of homes in your price range, up to about $250,000. That’s what Jim Meyer, managing broker for the MeyerWorks real estate agency and the current Columbia Board of Realtors president, calls a “very strong seller’s market.”

“I don’t see demand from the buyers slacking any time soon,” Meyer says. “It’s been pretty strong.”

So there’s already an abundance of similar prospective homeowners in the area and a relative shortage of existing properties in your income bracket. Add to that the fact that most new homes that come onto the market are on the high end of that price range — or out of it altogether — and you’ve got the makings of an affordable housing issue.

“There’s a shortage of entry-level homes — and I mean priced right, move-in ready homes,” says Sean Moore, president-elect of the Columbia Board of Realtors and realtor with the Sean Moore & Associates affiliate of RE/MAX Boone Realty. “There are plenty of entry-level homes, but the ones that aren’t selling are not priced right for their condition.

“You can’t build a starter home in Columbia anymore,” he continues. “The guidelines, the regulations, the cost of permitting materials and the land — there’s no margins. There’s no profit.”

The same trend is showing itself in Columbia’s commercial real estate market, where the city’s steady growth and healthy demand for properties have led to vacancy rates across office and retail properties that are about half of the national average.

It’s a sign of a healthy local economy. It also means there’s more competition for vacant properties and rates that price some smaller proprietors, like those looking to start or expand a business in Columbia, out of the market.

And, if commercial-zoned properties don’t develop at a rate that matches the demand, the problem could get worse.

“We have a shortage of supply in town, and that is exclusively driven by government and restrictions on commercial zoning,” says Jason Gavan, an agent at House of Brokers Commercial Realty. “We’ve got decent and steady demand, which is always a good thing to have. But we don’t live next to an ocean. We don’t live next to an enormous national park. There’s no limit on land in Missouri. What limits it is when government refuses to allow development of commercial-zoned properties, and that is a primary driver of prices.”

It’s a trend that affects middle- to low-income residents more: there’s a relative scarcity of affordable housing with which to lay permanent foundations in a community, and there’s competition for commercial space with which to lay a stake in the local economy.

“The largest investment anyone will make, typically, is their home,” Meyer says. “If people can’t afford to stabilize themselves by buying a home, they become more transient at great cost for employers. There’s a whole cascading set of impacts for employers when there’s not a local, stable housing market, in addition to the impact on the individuals themselves.”

Automatically Expensive

For a time, the fix-and-flippers left the Columbia real-estate market.

When the recession hit, almost a decade ago, the segment of the population that would buy an old house, fix it up, and then put it back on the market for a higher price disappeared. Moore says he’s starting to see more fixer-uppers when he’s out on house-finding expeditions with his first-time homebuyer clients.

“This is the most opportune time I’ve ever seen in my lifetime to become a fix-and-flipper,” Moore says. “I think there is a vacuum, a void in our marketplace for that. I think a lot of money can be made.”

The reason, as Moore sees it, is the lack of affordable new housing in Columbia. First-time homebuyers typically want new construction, but if it’s out of their range, he says, refurbished older houses can fill in that gap.

As recently as a few years ago, Meyer says, first-time homebuyers could look for new construction in the $120,000 to $130,000 range. The cheapest new construction he’s seen on the market within the city limits this year is a 1930s-style cottage bungalow in the central part of town on an infill lot — added onto an existing neighborhood — listing for $168,000.

“Everything else is in the $190s or above,” Meyer says. “A lot of [homebuyers] are not going to make that jump. They are frustrated.”

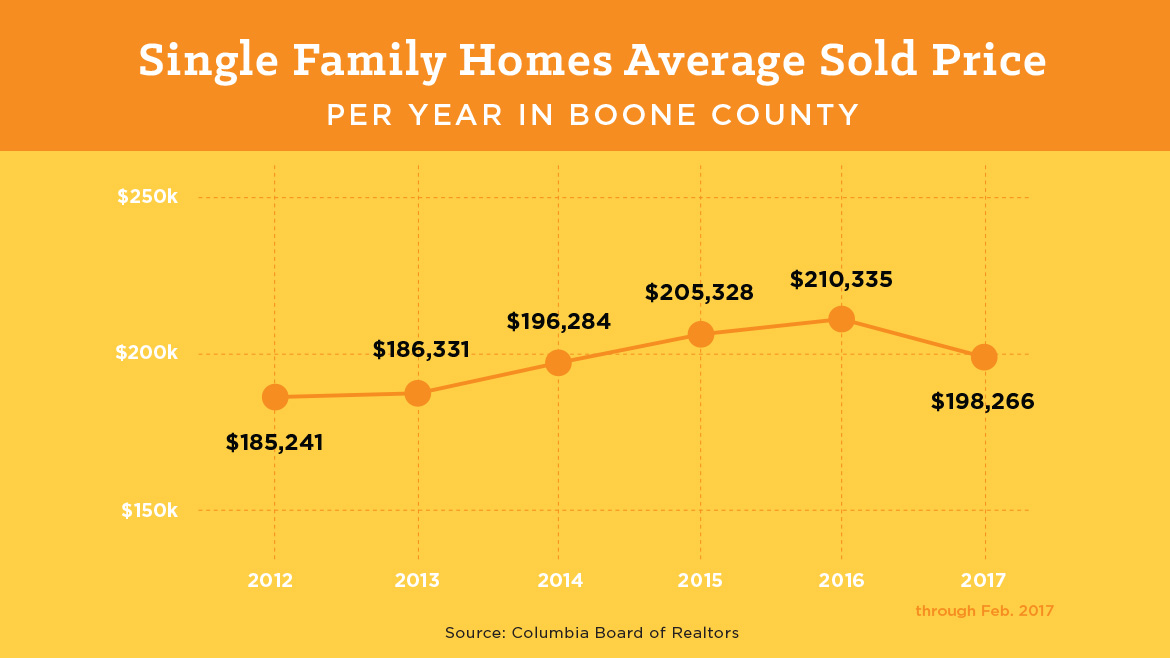

According to Missouri Realtors research, the median selling price for homes across the state was $144,000 in February, an increase of nearly seven percent from February 2016 and nearly 11 percent from February 2015.

In Columbia, according to MeyerWorks research, the median selling price for all single-family homes from March 2016 through the end of February was $171,000, an increase of a little more than two percent from the previous year. The number of new listings in the city dropped three percent, and the number of total active listings on the market dropped six percent.

On the whole, there are fewer choices. And the choices that exist are getting more costly. New construction is only about 10 percent of the market in any given year, Meyer says — but it’s a highly influential 10 percent.

“If new construction continues to increase in cost far above the rate of inflation, then there’s going to be a perpetual sellers’ market for existing homes,” Meyer says. “It’s going to become more systematically out of balance because there are people who will be priced out of new construction and still want to buy. That’s going to create a lot more demand for existing homes and, eventually, they’re going to bid up the price of existing homes. Eventually the whole market can go up to the point where low- and middle-income people are priced completely out of the market. And they move up to Boonville or Fulton, Jeff City, Ashland.”

State Senator Caleb Rowden, who represents Boone and Cooper counties, has introduced a bill aiming to help people in this situation statewide. The legislation, Senate Bill 444, would establish a first-time homebuyer savings account, in which individuals or couples filing jointly could put aside up to $16,000 or $32,000 a year and then deduct half of the amount they save from their income taxes.

If the bill passes, (at the time of this writing, it was being debated in Senate committee — the Senate session ends in May) it would take effect on January 1. Rowden says that, while he could see some pushback from legislators on the right and left who object to anything resembling a “tax credit,” he feels the sentiment of the bill should receive broad support.

“It gives first-time homebuyers the chance to either put money away in a tax-free environment, or allows other folks to invest in first-time homebuyers. Parents could put in dollars to a child’s first-time home savings account,” Rowden says. “We’ve been doing a lot of work on some policy matters that hopefully would really target the working poor and lower- and middle-class families. It’s just another opportunity for us to provide a path forward for someone who is living paycheck to paycheck. If we can be forward-thinking about the things that are possible in that realm, that’s a good thing.”

While Rowden’s bill addresses part of the problem from the homebuyers’ side, it can’t keep housing prices in an affordable range.

Moore and his team represent four smaller building companies in Boone County. He says a decent lot in Columbia goes for around $75,000. If you take a general rule of thumb, that a builder wants the lot to be about a third of the price of the house, that’s already pushing up into the $250,000 range.

There is a steady supply of homes in that price range in Columbia, largely because new construction is almost forced into that higher price bracket. Meyer worries, too, that the new Unified Development Code that the Columbia City Council passed in March will make these conditions worse.(For an in-depth look at the UDC, see page 50).

Meyer proposed a hypothetical situation in which a developer buys 100 acres to create a subdivision. Due to regulations in the new code on what counts as forestation in a residential area, a cap on 30 homes served per entrance, and rules about steep slopes and roundabouts being inserted in every four-way intersection, he says that the builder, in this scenario, can make 52 fewer lots than they could under the old code.

That, in turn, means the builder has to charge around 31 percent more for homes in their subdivision to recoup the cost that went into developing it.

“There are different public policy objectives, different people have different views about how much value to place on environmental preservation, stormwater management, street design,” Meyer says. “But the problem is, in my view, the city is doing nothing to do any kind of cost-benefit analysis. They’re just adding costs.”

No Vacancy Signs

Jackie Floyd and her partners hit upon some good luck when they were looking for a location to open their Smoothie King franchise in Columbia.

One day, they saw a “for rent” sign outside an old Mexican restaurant on Nifong. It was at the end of a strip mall and had a drive-thru already attached to the building. Both things on their checklist.

The Smoothie King location opened in January 2015, and, seeing the sort of enthusiasm the community held for their services, Floyd and her partners started looking to expand.

They haven’t been quite so lucky this time around. Structures — either standalone or at the end of a strip mall — already outfitted with drive-thrus are difficult to find in Columbia, and landlords are hesitant to commit to building a drive-thru for a store that uses as little space as a Smoothie King.

“There just needs to be a few more commercial properties, really. Better options,” Floyd says. “I may have to just settle for a non-drive thru if I want to expand. There can be some more properties. Tenants may shoot for the moon, but they also need to have a Plan B.”

Plan B, in Smoothie King’s case, has involved looking elsewhere. Floyd and her partners opened a second location in Jefferson City, and then a third one in Kirksville at the end of March.

“When it comes to running your business, if there’s not a great location, I’m just going to go somewhere else where there is a good location,” Floyd says. “That’s what we’ve done. But we’re still looking in Columbia.”

When it comes to commercial real estate in Columbia, some areas of town have more hotly contested vacancies than others.

In the north, there’s less commercial space than other areas because the demand isn’t as high. South of downtown, where off-campus housing flourishes, is a boom area, and more properties are starting to pop up in the east as the population base shifts there. The mall is always a competitive area, thanks to the regional traffic coming off of I-70.

And downtown? Well, it’s packed to the gills.

“Our vacancy rate is less than three percent downtown. That’s just outrageously low,” says Mike Grellner, vice president of Plaza Commercial Realty. “If you’re in downtown and want to expand, there are very few choices down there.”

According to research compiled by Plaza, Columbia has a 5.1 percent citywide vacancy rate for office space, 5.9 percent for retail space, and 7.3 percent for industrial space. The national averages for those three types of commercial real estate are 9.9, 11.5, and 7.9, respectively.

The demand is healthy. That means the economy is healthy. With such comparatively low levels of vacant commercial space, Grellner says it’s critical that Columbia-based businesses continue to have enough room to expand or start fresh.

“For those that make their living here, that are interested in a robust local economy, it’s of the utmost importance. As a community, we have to appreciate development of all kinds. It’s where people are earning a living, are fulfilling a role or a job that helps this local economy thrive,” Grellner says. “If suddenly there’s a lack of space to allow businesses to do that, whether they’re new or existing businesses in this community, I believe that’s a real problem for Columbia. It’s critical we recognize the importance of space availability for job creation.”

Grellner says there has been more commercial space construction in Columbia over the past few years than in the five-year period preceding it. Some of it, such as MU-related construction, was already spoken for when it went up. Some of it, such as Discovery Park in southeast Columbia, was speculative.

It becomes an issue, according to Gavan, when local government imposes undue restrictions and guidelines upon commercial-zoned properties. The rising costs that result can dissuade prospective developers from expanding upon their properties or making the effort to convert properties zoned for other purposes into commercial.

“Let’s say you buy a piece of agriculture-zoned private property and you’re going to turn it into commercial private property,” Gavan says. “If it becomes cost-prohibitive to convert that into commercial-zoned land, then either you’re not going to do it or you’re going to pass that cost onto the tenants or buyers of that property.”

It can also drive away prospective tenants. Gavan says he’s had clients from Kansas City and St. Louis tell him they can get similar properties in those cities for a third of Columbia prices. He’s had others who search for properties with him for two to three weeks before deciding to take their business to smaller Mid-Missouri markets such as Fulton or Boonville.

“The solution is for municipal governments to stop blocking private development,” Gavan says. “It’s like we’re creating a solution for a problem that shouldn’t exist.”