MU Professor within Reach of His Board Game Dream

Mark Swanson has childhood memories of moving paper pieces around a homemade board and rolling croquet balls down a long hallway, trying to land them on numbered construction paper circles. Gaming has always been a part of him.

“We were kind of a poor family growing up, but that didn’t stop my dad,” Swanson says. “He was just always very inventive when it came to family entertainment, and that stuck with me.”

After many games played throughout adulthood, Swanson, an advertising professor at the MU School of Journalism, went back to the cardboard and paper pieces of his past. He’s been polishing his own board game, “Feudum,” a medieval themed Euro-style game in which players compete for prestige in different guilds. Swanson is ready to begin fundraising for his game on Kickstarter this fall.

“When you play hundreds of games — and I’ve played hundreds — it’s hard not to imagine that game that you would create, and I one day decided to set out to create the game that I’ve always wanted to play.”

What’s Euro-style Anyway?

Swanson discovered Euro-style board games in the late ’90s and was immediately intrigued. What was distinct about these games? Did Germans have a monopoly on the board game market? Speaking of Monopoly, what about American board games? What’s the difference?

Euro-style games are often more complex and non-linear. “Settlers of Catan,” what Swanson calls the “gateway game,” features multiple ways to win, a characteristic of many Euro style-games. They are games of strategy and intellect, rather than games of luck.

“After two hours of intellectual investment, that’s very unsatisfying — to lose because of luck,” Swanson says. “Enter German board games. Most of them mitigate the luck factor and they employ these wonderful mechanics, mechanics like resource management, area control, auctions and bidding, and worker placement.”

“There’s something about sitting across the table from someone and moving wooden pieces around the board,” he continues. “It’s tactile. It’s substantial. It’s intimate. It excites the brain.”

Taking a Village on Kickstarter

When he started creating “Feudum,” Swanson drafted the game on a large piece of cardboard. Using wood and folded paper as game pieces, he and three friends tested the game. It took entirely too long, Swanson remembers; the first play-through took seven hours. This is how all games begin, Swanson says, even the Euro-style greats (such as “Le Havre” and “Viticulture” by Uwe Rosenberg and Jamey Stegmaier, respectively). Game authors develop a puzzle and a world of characters.

In the quiet yet enthusiastic niche of board gamers, play-testers play through the games and review them, releasing early opinions into the community of gamers via blogs, YouTube channels, websites, and conventions. Excitement stems from there. Swanson’s game is highly anticipated by online members of the Euro-style community. One prominent game reviewer, Richard Ham, better known as “Rahdo Runs Through” online, has put “Feudum” on multiple annual “Games of Interest” lists. Ham says he hopes this is, finally, the year that “Feudum” launches. In a video review, Ham says, “If I were ever to design a board game, this is probably the game I would design.”

The gaming community is a valuable part of the process, especially for Swanson, as the fundraising for his game will begin on Kickstarter in the coming months.

“I think, even though it’s been around for a while, the concept of crowdfunding is still novel for many people” he says. “Kickstarter and Indiegogo and other crowdfunding sites sprang up and democratized the entrepreneurial process. Now, the money can come from the consumer, who says, ‘I will pledge this amount of money to pre-order the game, and you can use that money to manufacture it.’ It’s a brilliant concept, and it has resulted in games seeing the light of day that would not have otherwise.”

Swanson, who has worked on advertising for corporate giants like Coca-Cola, Oscar Meyer, and Kraft, knows a thing or two about marketing to an audience, but he’s still slightly uncomfortable with it on such a personal level.

“I get that there’s a place to market and advertise. I mean, I teach it for a living,” he says. “But things of value, things of true value, have a way of finding their way to the surface. They don’t need a lot of help.”

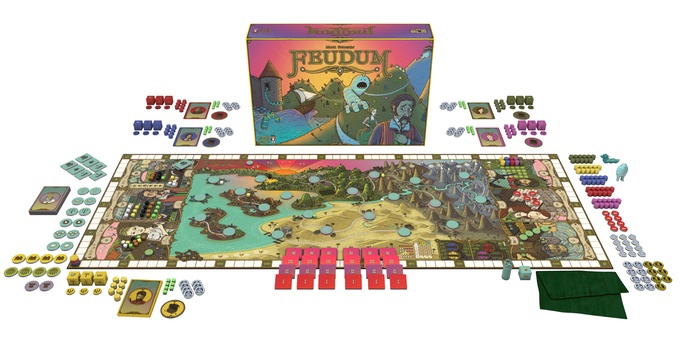

Swanson has paid the utmost attention to detail. His game pieces are custom-carved. His cards have a woven-linen texture. One of his biggest challenges, he says, was finding the right artist.

A band poster in Sparky’s Homemade Ice Cream, designed by a man named Justin Schultz, eventually caught his eye, and after some searching online, Swanson connected with Schultz, an artist and graphic designer from Jackson, Mississippi. Schultz’s etch-styled behemoths, mermaids, and bearded knights in greens and turquoises make the game visually cohesive.

A band poster in Sparky’s Homemade Ice Cream, designed by a man named Justin Schultz, eventually caught his eye, and after some searching online, Swanson connected with Schultz, an artist and graphic designer from Jackson, Mississippi. Schultz’s etch-styled behemoths, mermaids, and bearded knights in greens and turquoises make the game visually cohesive.

Swanson will produce 1,500 to 5,000 replicas of the game through Panda Manufacturers, a game manufacturer based out of China and Vancouver. Their printing press will produce the copies of the 42-inch-by-16-inch accordion-fold board game.

The games will be stored all across the world; they are shipping-friendly in the United States, the EU, and Canada.

After the initial printing and reviews from several more game authors and players, games typically go through a second print, Swanson says, though that all depends on feedback from the audience. Swanson’s Kickstarter page will go live in the fall, and, if funded, the game will be released next year. In the meantime, fans can follow the game on Facebook.