Discovering the History of Trains in Columbia

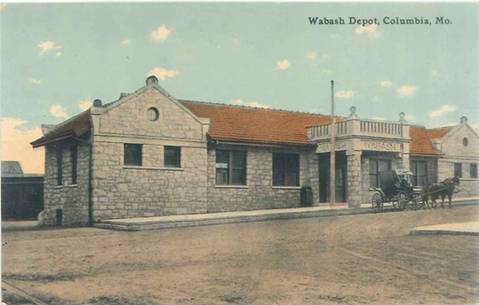

Today, the rail lines running through Columbia are mostly invisible. People walk through the yard behind Wabash Station on their way to brunch at Café Berlin, or grab a drink at Shiloh (formerly Katy Station), or run along the MKT Trail, where passenger trains once shuffled people into downtown and out through Boone County.

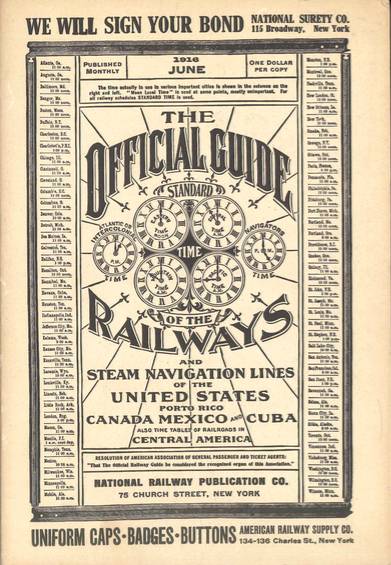

After driving past Wabash Station this past weekend, I offhandedly mentioned to Al Germond, CBT’s owner and opinion columnist, that I’d be interested in tracking down some info about trains in Columbia. He told me to wait a couple minutes; he returned with a book titled, “The Official Guide of the Railways and Steam Navigation Lines of the United States, Porto Rico, Canada, Mexico, and Cuba: Also Time Tables of Railroads in Central America.” The book is slightly thicker than the height of my thumb, and it’s only the June 1916 edition — they were published monthly. You could get a copy for a dollar. (This is why Al is one of the best people to offhandedly mention things to.)

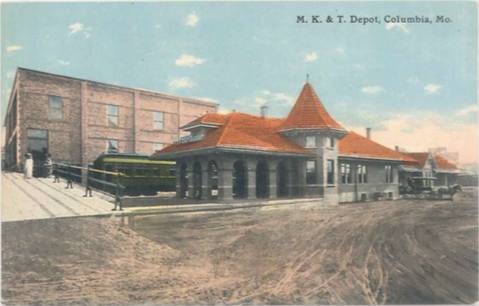

In June 1916, and for most of its history, Columbia was served by two big train lines: Wabash Railway Company and Missouri, Kansas & Texas Lines, abbreviated as MKT Lines, nicknamed “Katy.” Once he set the book down, Al started flipping through the pages until he found the schedules and maps pertaining to mid-Missouri, on pages 121 and 1100 (out of 1600).

To me, someone who has never had to take a train, the book itself is a magnificently indecipherable work of art. The maps are printed with painstaking detail, marking every stop and all the nearby towns in roughly six-point type. The schedules are dense data tables of departure and arrival times that, in theory, relate to each other, though it doesn’t look that way — a series of long columns with various times runs down the left side of a middle column, which bears different station names, and another series of time columns runs down the right side. These timetables can be humbling documents to examine. On one of the Katy regional maps, covering the lower Midwest, Columbia is on a barely identified line tucked between a fork that the main line takes in New Franklin (which, judging from the type size, was about Columbia’s size at the time.) Having to strain my eyes to see Columbia on this railway map gave me a refreshing sense of perspective — here I was, one of thousands of people inhabiting a tiny speck of ink stamped onto a piece of old paper with thousands of other tiny specks of ink that were also homes to thousands of people.

Railroads, back when they were important for everyone, were particularly important for Columbia — it was how college students got to school every year at MU, Stephens College, and, as Columbia College was then known, Christian College. In June 1916, any students left in Columbia would probably have been returning home to another city — let’s say St. Louis. To get from Columbia to St. Louis on the Katy, the student would hop on a train at Katy Station (students have always liked that building, it seems), which would then take a half-hour trip down to McBaine before making the approximately 5-hour trip to St. Louis. Without the burden of having to dodge trucks on I-70, the student could take his or her time enjoying the fine stretch of Missouri between here and there: the hills and forests, lakes and creeks. The thought of it seems peaceful.

But trains were doomed to fail. People started driving, and driving was fun — who would want to sit on a stuffy old train when you could be the conductor of your own vehicle? Katy Station stopped serving passengers in 1958; the Wabash station held on a little longer, ending passenger service in 1969.

Columbia has done a noble job of repurposing its rail lines and stations. The City purchased Wabash Station in 1979 and started using it for buses a few years later. That building still houses COMO Connect’s offices, and a series of paintings by local artist David Spear pays homage to the station’s history. The MKT rail-to-trail project was well executed. From 1976 to 1998, the Katy Station building was a railroad-themed restaurant, complete with train cars that had been modified into seating booths. The city has revived the Columbia Branch Railroad, which ran from Columbia to Centralia, for the COLT Transload rail service. Those rails also served the Columbia Star Dinner Train before a financial dispute between the City and the train’s owner closed the line in 2014.

Al, by the way, got the railways book by way of his brother, who was a train fanatic. I think I’ll try hanging on to the book for a while longer — it’s fun to track the invisible lines that once winded around here.