Forever Loved

+12

+12 Denise McDaniel’s story is a series of lessons on heartbreak and healing. She’s still teaching those lessons to her big family at Coyote Hill Christian Children’s Home.

For some people, it takes a few false starts to find a passion in life. Others build on their natural talents and fit easily into a chosen career. And then there are those whose experiences and struggles have uniquely shaped them to meet an extraordinary calling.

Denise McDaniel falls squarely into that third category. She and her husband, Larry, run Coyote Hill Christian Children’s Home in Harrisburg, and for nearly 25 years, the home has provided love and care to foster children from the surrounding counties. Denise’s story has been a part of Coyote Hill’s for 20 of those years.

Fostering and Widowhood

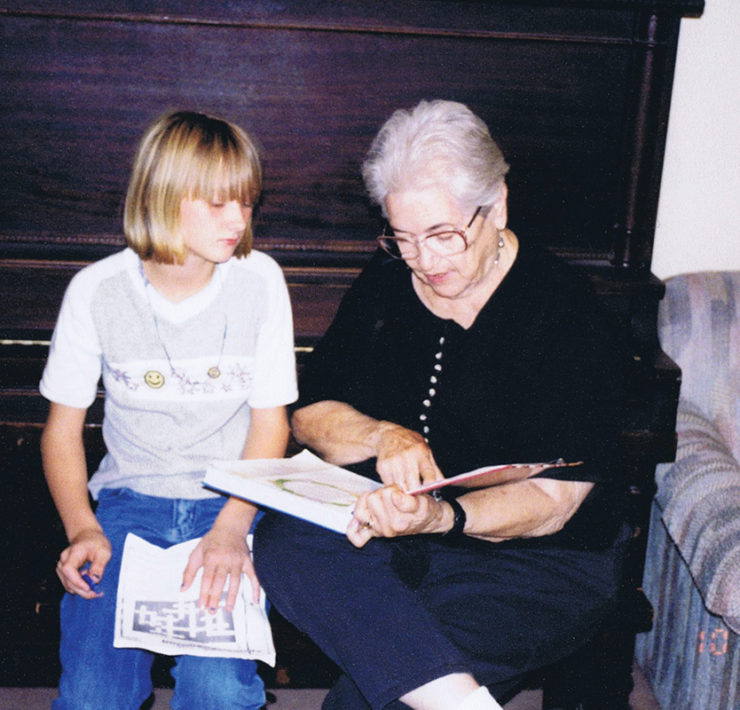

Denise grew up in Iowa, in a setting that many would find unusual. When she was still a toddler, her parents became foster parents. Denise’s childhood was filled with the comings and goings of children in crisis who desperately needed the love and attention that Denise was born into. By the time she left home, after high school, over two hundred foster children had passed through her home; her parents were once voted foster parents of the year. Growing up with these kids made Denise more thankful for what she had and more compassionate towards people in need. But she had no idea that one day she would be part of another foster family.

Denise met her first husband, Ryan, in college. “You know how that happens,” she says. “You fall in love.”

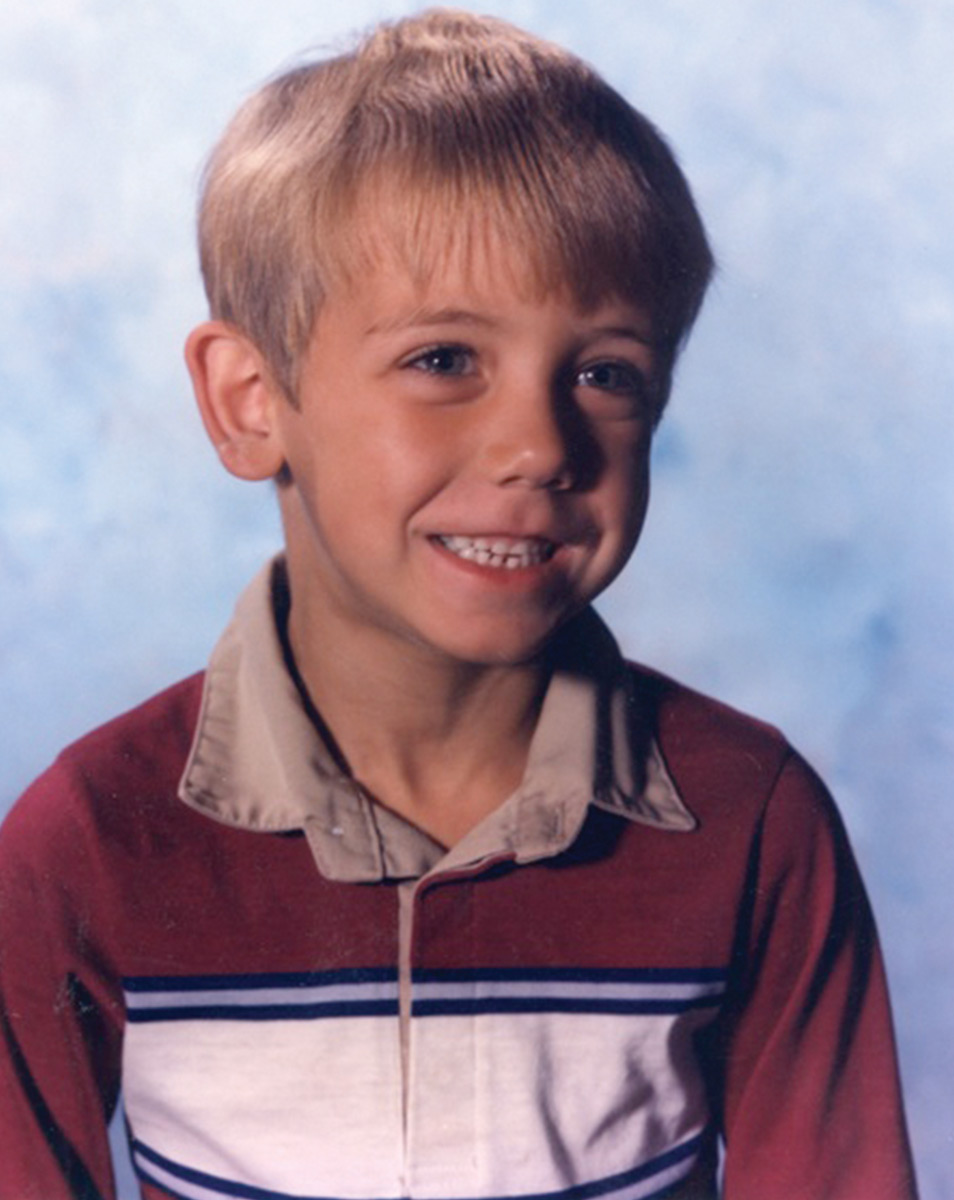

She had just started her master’s degree when she learned she was pregnant with her first daughter, Haley. She nannied from her house in Omaha, Nebraska so that she could be home with Haley; not long after came a second daughter, Abby. Then tragedy tore through the young family. Ryan, a firefighter, was killed when Abby was only 7 months old.

Denise grieved, and she learned how to make life work as a single parent. She continued nannying so that she could keep her girls with her instead of in daycare. For five years, she stayed in Omaha and raised her girls.

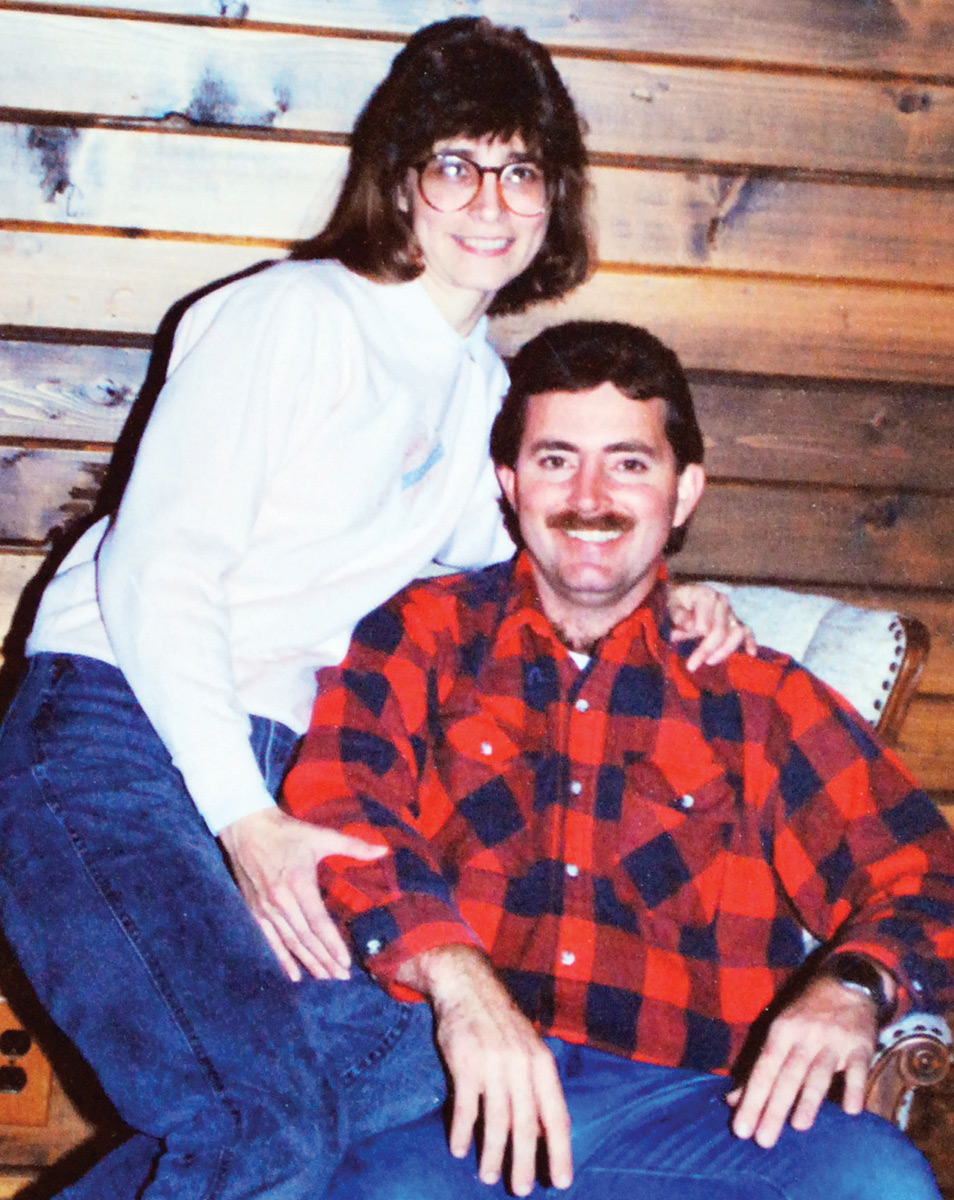

Then she got a letter from her cousin, Nate, who lived in Missouri. Nate’s close friend Larry had just been widowed, and Nate wondered whether Denise could write to him with advice on being a single parent. You’re further down that road, he told her. “Thankfully, there aren’t a lot of young widows and widowers,” Denise says.

So they wrote to each other. “It was through our letters that we fell in love,” Denise says. “We never met until we got engaged. Letters and then phone calls, and then the day he came to meet me, he brought my ring.”

Denise hadn’t expected to fall in love again. “[Ryan] had been gone for five years already,” she says, “and I had worked out being a single mom pretty good. I loved my little girls. We were making it. I didn’t think I would get married again. And so I had said to my friend — this is how important friends are — ‘I’m going to need proof if I’m ever going to get married again. So I’m going to need God to write a sign in gold across a blue sky that says, “I’m the one,” and then I’ll know.’”

Denise’s friend knew that, with Larry, Denise would be happy. When Larry showed up at her door, he was wearing a blue sign with gold lettering that said, “I’m the one.”

The sign is still in their bedroom today.

The Beginning of Coyote Hill

Through their letters and phone calls, Denise learned Larry’s story, his vision, and his heartbreak. He and his wife, Cathy, dreamed of building a foster home in a beautiful place where children could just be children. They met a couple who had about 80 acres in Harrisburg. That couple had bought it as recreational land, but the wife hated it — she couldn’t stand the howling of coyotes at night. She called the place “Coyoteville.” Larry misheard the name and thought it was “Coyote Hill,” and the name stuck. They bought the land.

Cathy and Larry built a big house on the property, which became home to their own three children and then to several foster children. The first foster child to come to Coyote Hill was named Anna. She was only five days old, and she had special needs. Cathy and Larry would eventually adopt her.

A page on Coyote Hill’s website reads, “Larry and Cathy’s experience in foster care led to a realization that there was a tremendous need for a professional home of love that was able to address the social and emotional issues, in addition to the physical ones of food, shelter, and clothing.” They knew it was time to expand their dream. Larry gave talks at local churches about their vision of creating “a safe place to be a child.” At one such talk, Mark and Laurene Zimmer came forward and donated nearly 200 acres of land.

Around this time, in 1993, Cathy was diagnosed with cancer. Her health declined rapidly. When she could no longer care for the children, she and Larry moved with their biological children into a small white house at the entrance to the new property. A series of house parents were hired to live with the foster children in Bill and Cathy’s place, ending with Bill and Tammy Atherton, who were house parents for 10 years. Cathy passed away in 1994.

“She was really the heart, I believe, of the ministry,” Denise says of Cathy. She speaks fondly of Larry’s first wife, whom she never met. When Cathy died, Coyote Hill was at a crossroads. It could have failed right then, after losing one of its founders, but Denise believes it survived because of the love that Larry and Cathy had poured into their dream. “It began with a mother’s heart,” she says.

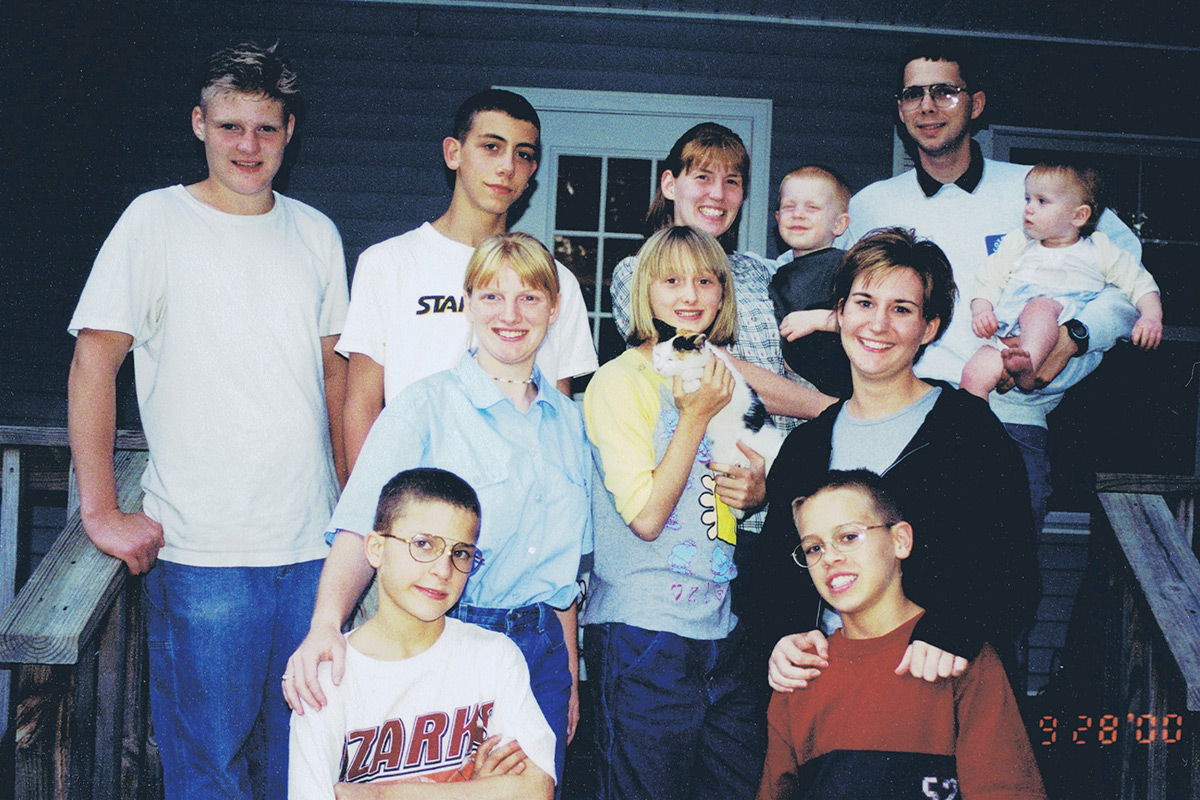

Denise and Larry were married in 1996, while the state licensure process was ongoing for Coyote Hill. They had six kids between the two of them; she moved to Missouri with her daughters, blending her family with Larry’s. Anna’s adoption had become official just before Cathy’s death. Denise embraced her four new children as if they were her own.

Growing up with Coyote Hill

Denise felt she had been preparing for this new chapter her entire life. Growing up with foster children gave her practical knowledge as well as a deep compassion for abused and neglected kids. That first year, in 1996, she offered to help plan the Christmas celebration. By 1997, she was the Christmas coordinator. Later, she would become a community liaison, speaking to any community group that would have her to spread Coyote Hill’s vision. As the director’s wife, she did whatever needed doing. “It was wonderful,” she says. The staff dubbed her “Executive Director of Odds and Ends.”

Larry and Denise’s new blended family grew up alongside Coyote Hill. On the Hill, as Denise refers to it, new homes were built and more house parents were brought in to care for the growing number of children. At their family home, in Columbia, the McDaniel children were a small army themselves. Splitting her time between the complex in Harrisburg and her home, Denise ran her family’s house much like those at Coyote Hill. At one point, her six children were attending three different schools. The Columbia Daily Tribune once sent a reporter just to watch the McDaniels’ morning routine.

It was certainly newsworthy. Every morning, the kids got themselves dressed and did their chores. Denise cooked breakfast did her daughters’ hair. Backpacks would be ready by the back door the night before. Each morning, the family read Bible devotions before heading out to school. Then Denise and Anna would walk the kids to Christian Fellowship School, which most of them attended. The two of them would walk back home so Denise could drive Anna to her school, and then Denise would drive out to Coyote Hill and work until the school day ended. Then, she picked up all the children, dropped them off, and picked them back up from various sports and activities, and then it was homework time. It would have been chaos without a well-planned routine. “Coyote Hill taught me a lot,” Denise says.

Structure was one of the biggest lessons she took from Coyote Hill. “Stability, boundaries, and structure — kids thrive on that,” she says. “They want to know that they have limits. They want to know that someone’s going to stop them if it’s dangerous.” This is what Denise and Larry wanted for their children. It is also what every house parent provides for their Coyote Hill kids.

Denise continues: “Safe boundaries are so necessary in a child’s world. Does the person who lets you have fun and run in the road really love you? No. It’s the person who stands by the side and says, ‘You can have fun here, in the yard, but I’m going to keep you from getting run over because I love you.’ You might test that a time or two, but pretty soon you’ll know, yeah, she does love me.”

This idea of structure continued to evolve at the McDaniel home, and it still does at Coyote Hill, as house parents learn where to be flexible and what each individual child needs. Most foster children never had those lovingly placed boundaries in their former lives. It gives them a sense of safety that many of them didn’t know existed until they arrived at the Hill.

Soon, the community of Coyote Hill rallied around the McDaniels as tragedy struck once again. Their daughter Amanda was diagnosed with bone cancer during her first year of high school. Larry had to take time off to go to Houston with her for treatments. There was never a question of whether he’d be able to. The Coyote Hill family made it possible, managing the work in his absence, and when Amanda passed away, several hard years later, the Coyote Hill family grieved together.

The house parents of Coyote Hill are no strangers to emotional strife, and it takes its toll. Denise and Larry have made sure to give the parents weekly date nights and time to relax and recover. Denise explains: “You have to have time off. If you ever want to talk about strong women or incredible women, come to Coyote Hill, because what [the house parents] are called to do there is absolutely some of the most wonderful and some of the most difficult work I’ve ever seen done. Both. They get children who are so broken and so hurt. And that breaks our hearts. But if that’s your child you love, oh my goodness, the emotional toll on their hearts is just incredible.”

Coyote Hill gives the house parents regular breaks and support for their marriages. “If it broke our house parents, then it wouldn’t do the kids any good, and then we’d have damaged another family. So people’s marriages became a priority really quickly,” Denise says.

But the children who come to Coyote Hill have greater needs than their house parents can meet alone. Usually victims of neglect and abuse, the kids of Coyote Hill have a lot to work through. Each child at the Hill receives weekly counseling. Kari Hopkins, Coyote Hill’s development director, explains: “They’re doing incredible work there [in counseling] just to talk through what they’ve been through so that, when they leave, they can talk about it without breaking down. But sometimes that means that, well, [the kids are] going to be angry at home as well . . . One step forward, two steps back.”

Denise agrees. “Those kids test everything our parents say. Because no one’s ever been honest or stayed solid to them, they want to see: if they get too mad, will you kick them out? If they say, ‘I hate you,’ will you call social services? Our parents stand in that gap all the time for those kids while they build that bridge.”

Every aspect of Coyote Hill has been carefully planned to help the kids build those bridges. The houses are spaced out so that the place feels like a neighborhood instead of a commune. Kids attend school in Harrisburg and have daily activities and chores. They get riding lessons as well, at Coyote Hill’s own Overton Arena. What the children don’t know is that the staff members there are trained in equestrian assisted psychotherapy. “A horse is not just a horse,” Denise says. “The kid doesn’t know, but the horse is there to help them find emotional release . . . Every decision that is made at Coyote Hill comes down to what is best for the kids.”

A Legacy

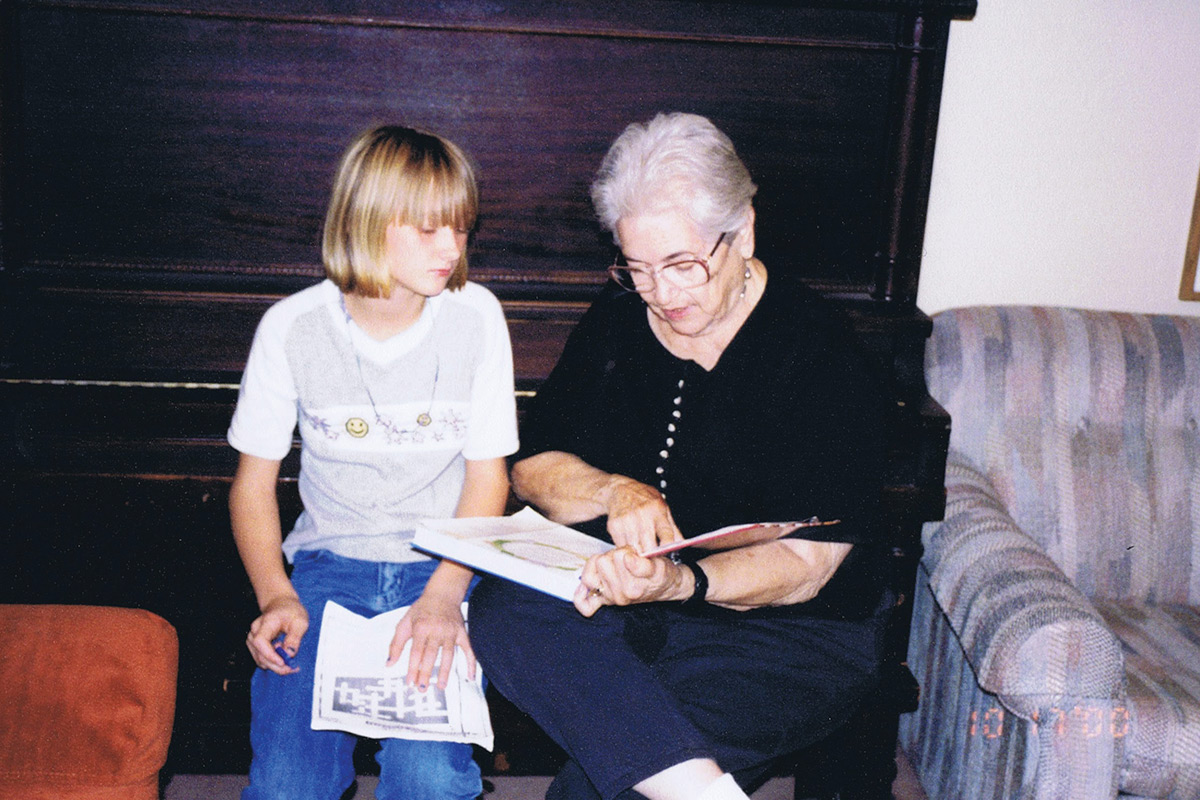

Nowadays, Denise is known to the kids at Coyote Hill as Grandma Denise. If a child has a bad day, Larry will bring him or her home to get some one-on-one grandma time. And she still helps with Christmas. Some children ask for extra gifts for siblings who still live with their biological parents and might not get a present at home. Teenage girls will sometimes request a Barbie doll because they never had one as a child. Denise loves making those dreams come true. When asked if she could ever see herself or Larry retiring, she laughs. Coyote Hill is too much a part of her to even imagine leaving. And as for Larry, “Someone will probably call me someday and tell me to get him off the property — ‘He’s wandering again,’” she jokes.

But she stresses that Coyote Hill can and will survive without them. It has to be bigger than two people. “I hope that when Coyote Hill looks back, they will find pieces of my heart that helped build the foundation,” she says. “But if it failed when I was gone, when I couldn’t be there, what would that have meant? It would have meant that it was just for us.”

Coyote Hill will celebrate its 25th anniversary in September. They’re currently planning a fifth home for the property. As for Coyote Hill’s future, Denise is confident that it will continue to draw people who want to help children in need. With tears in her eyes, she says: “Coyote Hill doesn’t just save children. It really saves us. Every heart I know that has been there, they are different today because of their time on the Hill. It brings out the good in you. Sometimes, it brings out the bad in you, because it makes you face things that you don’t want to face. But overall, the Hill really heals people. It’s a place of healing for every person who comes and is a part of it. If I walked away tomorrow and never saw it again, I still would be different because of my time there.”