The Greenest House on Earth

Local architect Nick Peckham leads the passive build industry.

I turn onto Country Club Lane looking for the “greenest house” I can find. I’m imagining a house made entirely of glass, or one with a large sculpture made of recycled soda cans built into the shape of Mother Earth.

The only thing architect and homeowner Nick Peckham told me was to look for the orange house. I hope to myself that isn’t the final color. And is this house going to look like a spaceship?

Instead of a home from the future, I drive up to a home that, besides the orange rubber on the outside (insulation, and not the final color, I would later find out), seemed to fit right in next to its historic neighbor at 2011 Country Club Lane, the Andrew W. McAlester House, built in 1883.

As I pull into the long gravel drive, a small green and white sign catches my eye: “The Greenest House on Earth.”

“That’s the only thing I do,” Peckham says. “If you don’t want to do something that’s environmentally responsible, go get somebody else. It just doesn’t make sense.”

‘Is that Orange the Color?’

Peckham addresses the bright orange right away.

“The people down at the Country Club have asked me, ‘Is that orange the color?’”

No, it’s not. In fact, the final colors will mirror that of the neighboring historic home, with white siding and gray, fireproof concrete shingles lining the bottom half of the building.

“I wanted this to be a state-of-the-art green building,” Peckham says. “Everything I know is in here. Recycled content, water conservation, day lighting, zero energy. So many things are in this house that could be in any house. The people who built this live in Boone County.”

Peckham, owner of Peckham Architecture, used as many local vendors as possible, from Glidewell Construction to Manor Roofing and Restoration. The house, when complete, will be “net zero,” meaning it produces as much energy as it consumes, if not more.

LOCAL VENDORS USED

- Glidewell Construction

- Mark Hall Cabinetry

- Dave Griggs Flooring America

- Inside the Lines

- Manor Roofing and Restoration

- Thermocore of Missouri

- Nemow Insulation

- Boone County Lumber

- Alpan Windows

- Air and Water Supply

- Columbia Redi Mix

-

JD Kelly Excavating

-

Johnson Plumbing LLC

- John Dubinski Drywall

- Shane Garrett Painting

- InMo Electric

- John Hudson Masonry

- Eddie’s Garage Doors

- D&M Sounds

- Innovative Tele

- Designer Landscapes

- Greg Rackers

- Mike Adair

“If this is the only building that ever got built this way, it would be a quirk,” Peckham says. “But I hope it’s an example of how straightforward it can be to build the most efficient building in the state, in the country. I like to call it the greenest building on earth, but that might be a stretch.”

*Maybe Not on Earth…

…But Peckham says he hasn’t been disproven yet.

What the structure will be is a passive house. When finished, it will be the most energy efficient home in Missouri and certainly in the top two or three in the country, according to Lisa White, certification manager at the Passive House Institute of the United States in Chicago (PHIUS).

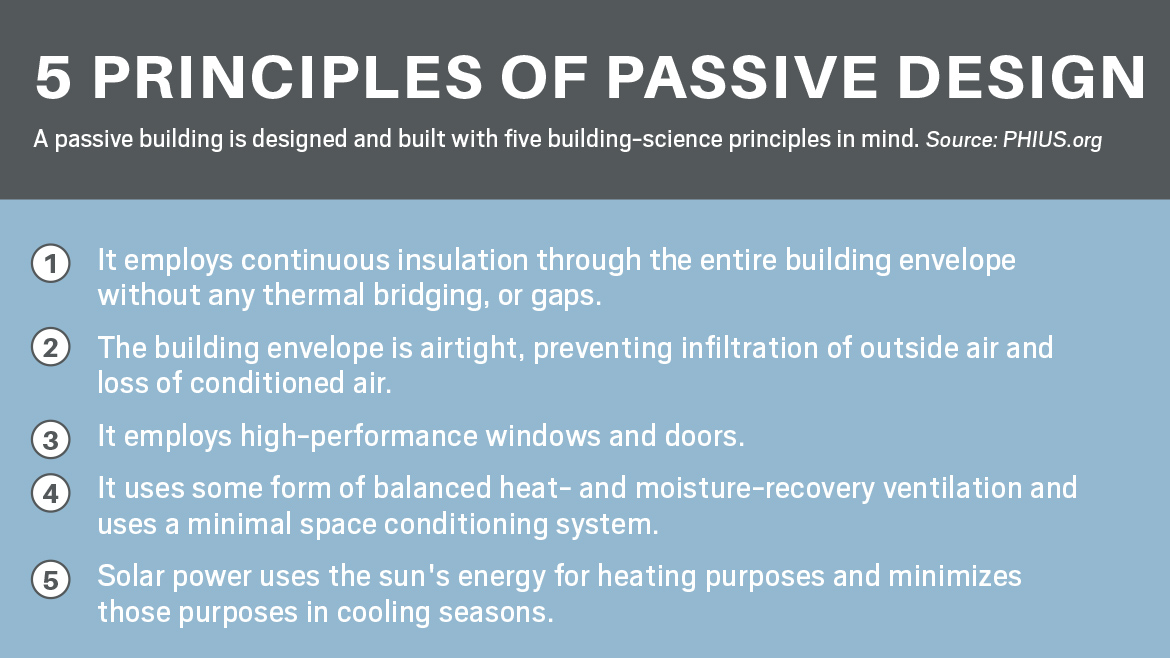

Passive houses significantly reduce energy usage, White says, especially space conditioning, or heating and cooling. Unlike LEED or ENERGY STAR certified buildings, certification for passive houses is not achieved via checklist. Instead, homes are built to exact Passive Building standards, and the builder works with a consultant to evaluate the design and energy model.

The idea was pioneered in the 1970s, with funding from the U.S. Department of Energy and the Canadian government, according to PHIUS.

The heating and cooling criteria are determined from formulas based on local climate factors, like temperatures, humidity and solar radiation. The heating criteria also depend on state-by-state energy prices.

According to PHIUS, the average passive building costs five to 10 percent more than a conventional building, and in general, the larger the building, the less the cost difference. Passive standards can be applied to any type of building, from single-family homes to skyscrapers.

“By applying a couple of passive principles, such as extra insulation in the building envelope, high performance windows, air tightness and then mechanical systems, that’s the recipe for passive building,” White says. “You’re just minimizing the heating and cooling demands of the building by properly designing the envelope.”

When Peckham’s house is finished, White says, it will be the first passive-certified house in Missouri.

“Depending on timing, this could be the second or third project in the U.S. to achieve this goal,” White says.

‘The Bleeding Edge’

When I meet Peckham in person, he’s conferring with general contractor Rod Glidewell, owner of Glidewell Construction, on the insulation. The exterior orange product turns out to be a premium rubber air and water barrier. Inside that are the Structural Insulated Panels. SIPs are high performing panels used in building floors, walls and roofs for residential buildings. They’re made by inserting special insulation between two particle boards and chemically bonding the insulation to the board. That bonding makes the insulation work better and helps control airtightness and air quality.

“I’m sorry, you can’t just put plastic on a building and hope that it’s going to be airtight,” Peckham says.

Though Glidewell has used sustainable products in his buildings before, this is his first completely “green” project.

“I was certainly glad just to have the opportunity to work with Nick,” Gildewell says. “It doesn’t matter how old you get: if you quit learning, you quit living.”

Glidewell and Peckham talk about the results of a blower door test, from just a few days before. Blower door tests examine the airtightness of a building, which helps conserve energy. Peckham reports they “nearly sucked the windows out of the house.”

Airtightness reduces energy consumption. The blower door includes a fan and is mounted into the frame of an exterior door. The fan pulls air out of the building and lowers the air pressure inside. The higher-pressure outside air then flows into the building through any unsealed cracks and openings, which helps detect air leaks.

The building code states there should be no more than three air changes per hour at 50 pascals. The Peckham house tested at two-tenths of an air change at 110 pascals.

In addition to pre-certification through PHIUS, the house will also be LEED Platinum certified and Energy Star certified.

“This is absolutely the bleeding edge,” Peckham says.

Home Tour

The front porch will be bricked with 100-year-old Edwards Brick Company bricks that Peckham has recycled four times already.

“It’s not a curvy, stainless steel type building,” Peckham says. “So it has that respect for history.”

The exterior is piped with downspouts to collect rainwater in different locations around the house, which will lead to a 1,000 gallon water container buried in the backyard. That water will be used for gardening. The roof will include solar panels to collect solar energy, the house’s main source of power. In the summer, the panels will produce more than needed, and the excess will be put back into the grid.

The 4,400-square-foot house is divided into three parts: the front part includes living space like a three-season room, kitchen, dining room and living room; the middle will include Peckham Architechture’s office; and the back third is sleeping space, with three bedrooms.

From Backyard to Forest

Peckham has been doing sustainable work for 40 years. His passion for sustainable building stems from his experiences in U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, in Kings Point, New York. As part of his training, he traveled to every continent, saw different cultures, religions and ways of life, and realized how small the planet is.

He later studied architecture under Buckminster Fuller, an American architect who invented the geodesic dome.

A caring attitude for the environment started at childhood. Peckham would go on long walks with his mother, and she would take a paper bag with her to pick up trash along the way.

“My dad’s idea of a good time on a Sunday afternoon was to go in a wood somewhere and dig up a small tree and plant it in the backyard,” Peckham says. “So the yard that was once a small piece of grass turned into a small forest by the time he was done. I don’t think either one of them was trying to save the world, I think they just thought that was the appropriate way to behave.”

Exceeding the Code

Many elements of the house aren’t particularly unique; they simply exceed building code requirements.

The ceiling is insulated with cellulose and is twice as insulated as the building code requires. The slab is separated from the foundation with four inches of insulation, connecting an “envelope” of insulation around the house.

The cement is mixed with fly ash, a recycled product that is a 25 percent substitute for cement and saves a large amount of energy in the cement-making process. The foundation uses a crush resistant foam to eliminate thermal bridging and retain heat between concrete and foundation.

The interior walls have fewer studs throughout, to minimize thermal bridges. Most houses utilize half-inch sheet rock. Peckham uses 5/8-inch sheet rock — it’s stronger, and it’s fireproof.

Mitsubishi heat pumps take energy out of the air to heat the house. And the house uses a recirculation pump, so no water has to go down the drain while waiting for the shower or sink to heat up. When the faucets turn on, there’s instant hot water.

Peckham chose Alpan windows — four times as energy efficient as standard windows — made with two panes of glass, with plastic designed for NASA in between.

When the house is finished, Peckham says it will have a $0 electric bill, and the city will buy back any excess energy from Peckham, though only at wholesale price, not retail.

“It’s not easy saving the world,” Peckham jokes.

The house cost $650,000 to build.

“I think that’s what custom homes cost,” Peckham says. “This one happens to be the greenest building on Earth. If people are spending that kind of money, they can get this. And obviously, if I wanted to build something for less cost, there are things that I might not have done.”

Baby Steps in Boone County

Sustainable practices come with a learning curve: like they did after using products such as lead paint and asbestos, Peckham says, builders eventually learn from environmental missteps.

Glidewell says it’s discouraging how unaware the general public is to sustainable practices.

“We learn from our mistakes,” Glidewell says. “But over 30 years, I built spec homes and would have hundreds of people come through the home, and it always astounded me that 95 [percent] of them would ask where I got the crown mold or what color the paint was and none of them would ever ask me, ‘How efficient is the furnace?’”

Barbara Buffaloe, City of Columbia sustainability manager, says there are more green building projects in Columbia than ever. But none like Peckham’s.

During the recession, Buffaloe says, she saw more interest in the cost-savings aspect of sustainability, but now she’s seeing an interest in creating a healthy indoor living space and having a positive impact on the community’s environment.

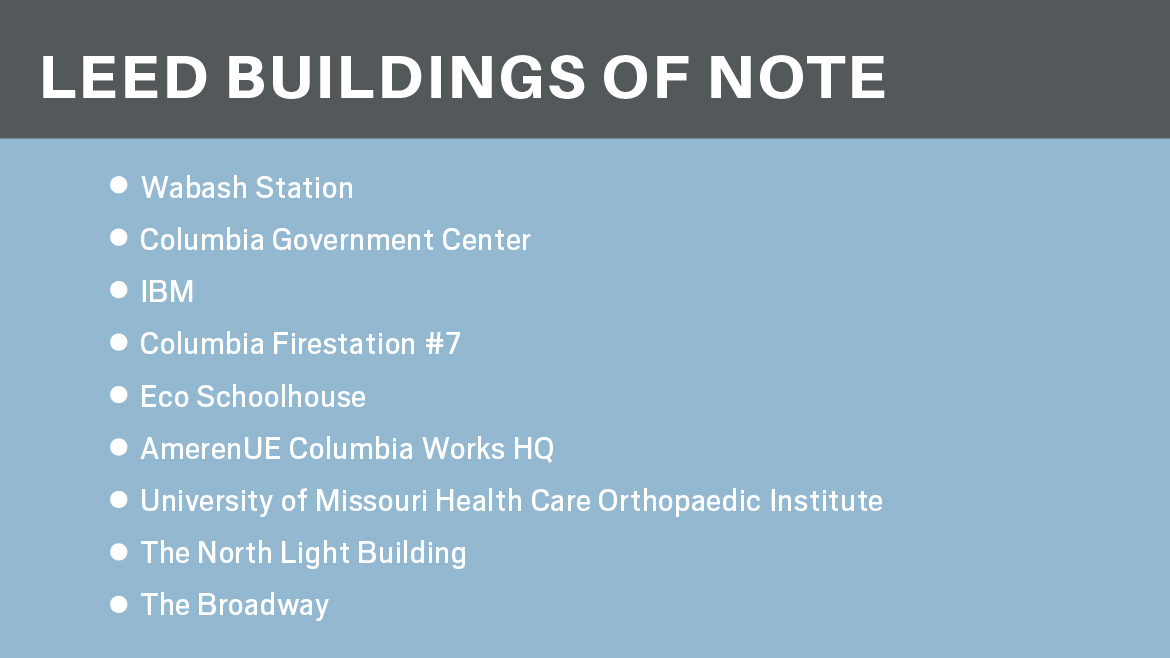

Buffaloe says she’s seeing an increase in LEED certified buildings in Columbia. According to the U.S. Green Certified Buildings Council, there are 27 LEED certified buildings in Columbia.

The city will soon award its second Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement Awards to recognize local businesses who are “walking the walk.”

The city is currently benchmarking sustainable practices with other similar cities through the STAR Communities certification, which is used throughout North America.

“From what I’ve seen, we’re okay,” Buffaloe says. “We’re on average. I think we have a lot of assumptions that we’re a fantastic, really progressive community. I would say that, for Missouri, that might be true.”

The benchmarking will help Buffaloe and the city identify next goals for improvement and compile ideas that can be used in Columbia.

Buffaloe says sustainable living doesn’t have to be more costly, and that sometimes there’s a perception that “outside that the norm” must mean more expensive.

“It just takes creative thinking and willingness to plan a little bit longer, rather than to just go with what your contractor might normally do,” Buffaloe says.

If sustainable living can become the new normal, it will be better for the entire community. But for now, Buffaloe says, it’s still a niche.

Spaceship Earth

Peckham says he sometimes finds himself criticizing the norms and standards in the building profession. But people are bound to follow the norm, and passive buildings aren’t yet the norm. Sustainable homes are his contribution to what he calls “Spaceship Earth.”

“A part of me says, we’re screwed,” Peckham says. “Because there are so many people who are starting from zero and trying to figure out how to feed themselves, let alone how to save the world, that it’s really a daunting problem.”

What must happen, Peckham says, is a change from traditional build to what he calls comprehensive anticipatory design science. That means contractors, sub-contractors, engineers, building officials and anyone else involved in the building process has to learn “100 times more” than what they currently know about building homes.

Right now, he is working with state legislators to hopefully offer tax credits for investments in renewable energy, which the federal government already offers.

After Peckham completes his house and moves in with wife, Diane, he’ll start work on a sustainable home directly behind his, for another local couple.

“Seeing that we’re all in this thing together, even though we don’t all know each other, even though it’s impossible to even know 115,000 people that live in Columbia,” Peckham says, “it’s hard, but I think we all have a responsibility to one another.”