Long Race for the Cure

MU’s cancer research team makes strides.

More than 34,000 new cancer cases were reported in 2015, according to the American Cancer Society. While some forms can be prevented, three MU researchers are making measurable progress in their research to eradicate the disease — but not without barriers in transitioning from research to mainstream medicine.

Doctors M. Frederick Hawthorne, Senthil Kumar and Kattesh Katti are taking different approaches in their cancer research and seeing favorable results in their testing.

Boron Breakthroughs

Hawthorne, the director of research for the Institute of Nano and Molecular Medicine at MU, has pioneered boron neutron capture therapy, or BCNT. The process involves injecting a cancer patient with a compound that contains Boron-10, which collects around cancerous cells and destroys them. Hawthorne has had success with his program in mice and small animals.

Research on BNCT has been ongoing since the 1930s, when neutrons were discovered. Hawthorne’s breakthrough is offering a cancer solution unlike anything in use today.

“This (process) is better than traditional chemotherapy,” Hawthorne says. “Chemo kills all cells. This just attacks the cancer, with no side effects.”

Common side effects of chemotherapy include hair loss, nausea, digestive problems, lack of energy and mouth ulcers.

Cancer cells grow faster than traditional cells, and as a result, they absorb more of their surrounding material. Hawthorne’s process takes advantage of this aggressive nature. The cancer cells take in more and more boron and subsequently destroy themselves, leaving the healthy cells intact.

Hawthorne’s BNCT process has achieved the same results multiple times in animals, specifically mice, with remission taking place in as little as a week.

“The research is ongoing,” he says. “The results are unique, mild, and we can do it again and again.”

Hawthorne’s BNCT work earned him the National Medal of Science, the highest award that can be given to a scientist “deserving of special recognition by reason of their outstanding contributions to knowledge in the physical, biological, mathematical, or engineering sciences,” according to the National Science Foundation. President Obama presented the award to Hawthorne in 2012.

Moving Targets

Kumar, assistant director of the Comparative Oncology and Epigenetics Laboratory at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, has been working on his project for 10 years. His research includes studying genes and identifying molecules to treat different types of cancers. Kumar says part of the challenge in his research is cancer cells adapting to drugs, pulling dormant cells out of remission because the cancer finds ways to combat treatments; when a new drug is used, another level of cells awakens and combats it.

“Our hope is to unravel the complexity of the [cancer] gene and develop a more effective drug,” he says. “When you use too many drugs, the problem is enhanced. The goal is to have a more personalized treatment.”

He says his work is progressing well, but a vaccine is still being sought.

Kumar, like Hawthorne, agrees that chemotherapy has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that cancerous cells are killed. But the healthy cells are also killed; there are side effects, such as losing hair, and the recovery is tough on the patient.

“We need to be careful in a targeted approach,” Kumar says. “We want to make sure we are not activating other bad cells.”

Kumar has seen progress in his chemotherapy research using both humans and dogs as test subjects.

Gold Rush

Kattesh Katti is the senior research scientist at the MU Research Reactor, and he’s working on shrinking prostate tumors using gold particles. According to the American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men (skin cancer being the most common). Annually, more than 220,000 men are diagnosed.

The chemicals Katti uses are non-toxic and come from the natural environment.

“Nanotechnology starts in the kitchen,” he says. “The highlight is that we are using chemicals in the human food chain — tea, mangos and soybeans. The rest of the world is using toxic chemicals.”

Toxicity, like that found in chemotherapy, can be devastating to the human body. This green nanotechnology seeks to avoid toxicity and could be used for both breast and pancreatic cancers.

Because the chemicals are natural, the costs associated with his process are significantly lower.

Katti says his process involves aggressively shrinking particles surrounding prostate cancer cells or, in some cases, eliminating the particles altogether.

“The results have been stellar in both small and large animals,” he says.

The process has been non-toxic to dogs, and Katti hopes to be able to begin testing on humans soon.

Prostate cancer will affect one in seven men during their lifetime, and 60 percent of those cases will occur when the patient is 65 or older. Katti compares prostate cancer to a car, saying as a car gets older, it’s more prone to problems. The same goes for other organs: the older the person, the more prone they are to problems.

Katti’s work has yielded global recognition. He received the Hevesy Medal Award in 2015, honoring outstanding achievements in radioanalytical and nuclear chemistry; was elected to the fellowship of the National Academy of Inventors; was named 2015’s Distinguished Professor under the Brazilian Scientific Mobility Program; received the 2015 Annual Oration and Award by the Society for Cancer Research and Communication; and landed on the Ingram’s 2015 “50 Missourians You Should Know” list.

Another process, related to Katti’s work but being done internationally, uses tiny gold spheres, smaller than red blood cells. Gold is unusual in that it is nontoxic and does not react to most compounds. These qualities make it ideal for medical use. One of the processes being studied around the world uses gold nanoparticles that are absorbed by cancerous cells and accumulate until they are acted upon by infrared light. The light heats the gold particles, resulting in an artificial contamination of the cancer cells, destroying them.

This type of treatment, called a “targeted drug therapy,” holds many benefits for patients and physicians. Targeted drug therapies can attack the cancer cells where they live, resulting in fewer side effects, and they can react with cancer cells at a specified time. The new methods are also less expensive and, in some cases, less invasive because they don’t require surgery.

Breakthrough Barriers

The Food and Drug Administration has a division tasked with examining nanotechnology and its applications in the fight against cancer. While not all drugs have been approved, the FDA acknowledges some of the benefits to nanotechnology, specifically targeted drug therapy.

According to the FDA website, “One of the drawbacks of conventional chemotherapy for the treatment of cancer is the inability to deliver the drug in adequate quantity to the tumor site without undesirable side effects. The major advantage of using nanomaterial as a carrier for anticancer drugs is the possibility of targeted delivery to the tumor.”

While headway is being made in the research realm, there are challenges that slow the process, one of which is the necessary equipment and facilities. Hawthorne has made progress, thanks to his national recognition, and MU currently houses the largest campus nuclear reactor in the country.

Another barrier researchers have is the process of testing on animals. Without successful tests on animals, it becomes difficult to move the process to human testing. PETA, for example, spends more than $15 million annually conveying their message against animal testing. This opposition often slows the animal testing process at MU. To combat the challenge, some research has been moved abroad where there are facilities and a culture that is more accepting to testing on animals. However, the same ethical challenges would eventually come into play internationally, and the research would then return to the United States while alternatives were sought.

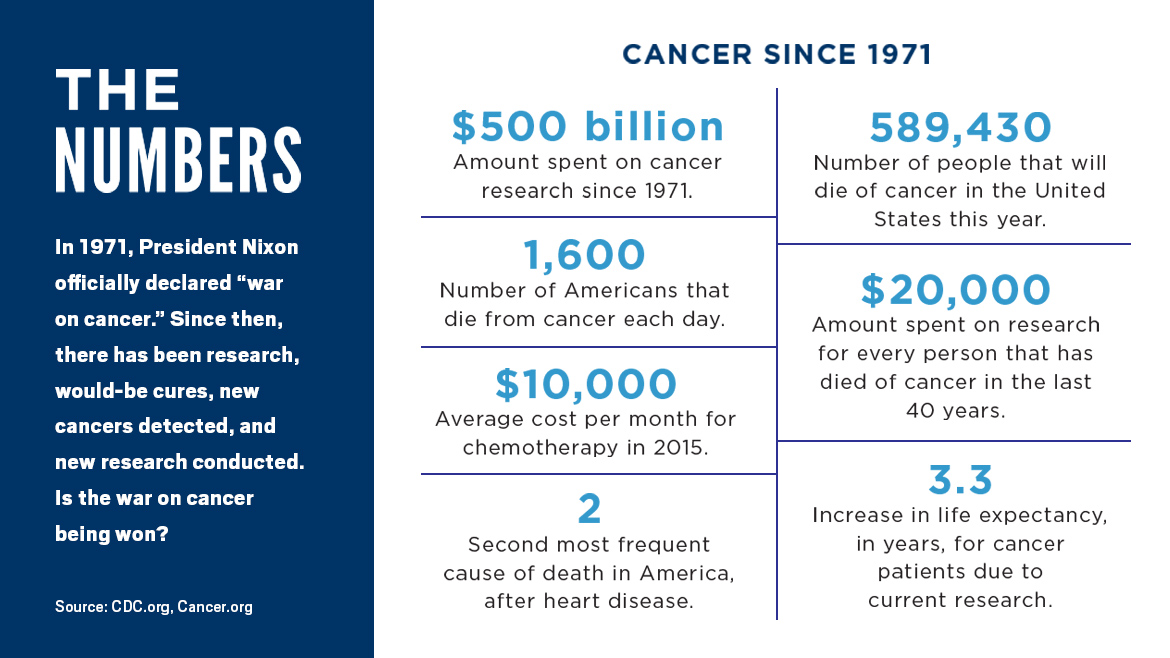

According to PETA, the United States has spent more than $200 billion on cancer research since 1971, and there are still more than 500,000 cancer-related deaths each year, an increase of more than 71 percent since the Nixon administration.

The group Americans for Medical Progress takes the opposite stance of PETA, saying animal rights groups are hurting medical progress. Through their website, AMP says their goal is to “protect society’s investment in research by nurturing public understanding of and support for the humane, necessary and valuable use of animals in medicine.”

AMP attributes humane animal testing for more than 50 percent of the gains made in cancer research, specifically targeted cancer therapies. Some cancers, like childhood leukemia, had a four percent survival rate in 1962. AMP says the survival rate is now more than 80 percent, with the help of the animals used as test subjects. Researchers have also made progress in breast cancer and lung cancer that used mice in testing.

The European Animal Research Association outlined more than 40 benefits to using animals as test subjects. Humans share more than 95 percent of our genes with a mouse; animals and humans have an organ system that functions the same way; and animals suffer from some of the same diseases as humans.

The EARA further attributes advances in cancer drugs due to testing on mice, and, in some cases, dogs, due to the similar natures in which the disease attacks both species. One of the benefits in working with dogs is that they are a larger animal, and, in some cases, cancer cells act in a similar fashion as they do in humans.

Kumar says one of his greatest challenges is not in the test subjects or the facilities, but in the cancer cells themselves.

“Trying to find the molecules that stop the aggressiveness [is the challenge,]” he says.