Game Day Green

On Saturdays in the fall, the flood of football fans around Memorial Stadium creates a world apart from normal life: an RV is more enviable than a sports car, a can of cheap beer is tradable currency, the best furniture is foldable, the attire is uniformly some shade of yellow and hoots and hollers are shared in an abstract language built on a tradition that’s sometimes decades in the making.

But despite everything that’s shared, this society is hierarchical. The veracity of one’s commitment — to the game, to the atmosphere, to the gear and, above all, to Mizzou — determines the pecking order. For some fans, this commitment is built over generations of support for Mizzou Athletics. Now, the university is asking for a bit more commitment.

The University of Missouri Athletic Department wants to raise more money, and by changing their donation model, they’re putting donor benefits on the line. But in an atmosphere built on tradition and commitment, change makes people nervous.

Southeastern pride

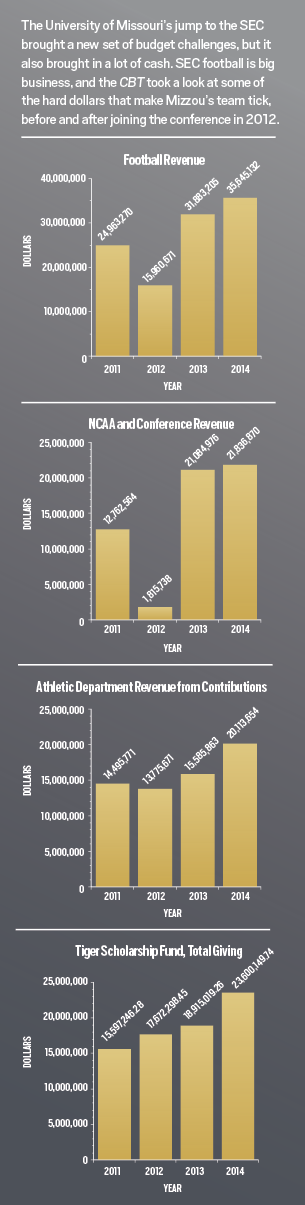

Schools in the Southeastern Conference do two things exceptionally well: play sports and raise cash. When MU joined the conference in 2013, it brought a history of athletic achievement with it — but it faced an uphill battle in its budget.

Every SEC school gets a share of conference revenue. At MU, this accounted for most of the $25.6 million, 50 percent budget bump that the athletic department had in its first full year in the SEC. But that conference money flows evenly to every team; donors supply the competitive edge.

that the athletic department had in its first full year in the SEC. But that conference money flows evenly to every team; donors supply the competitive edge.

Mizzou’s competitive edge is comparatively dull. It ranks 13th out of 14 SEC teams in private dollars raised.

“Growing our donor base is realistically the only way we can close the gap between us and the rest of the SEC from a budget standpoint,” says Chad Moller, associate athletic director of strategic communications. “We’re currently in the bottom three or four in the league in terms of budget, and we’ve identified the TSF as the biggest opportunity for growth.”

The TSF is the Tiger Scholarship Fund, the university’s primary vessel for private athletic fundraising. The athletic department distributes TSF money, however scant, to wherever it needs to go, but donor benefits focus on men’s basketball and football. Thus, those two sports drive the fundraising.

The Tiger Basketball team has underwhelmed everybody, including donors, in its first few years in the SEC. No remedy appears on the horizon; two of its three leading scorers transferred after the 2014-2015 season, when the team missed the NCAA tournament.

The football team, led for the past 15 years by head coach Gary Pinkel, picked up the slack. Against national expectations, Mizzou won back-to-back SEC division titles while producing All-Americans and reloading with strong recruiting classes. But more financially important, the team’s success has made it a marketable part of the SEC brand.

“[Changes to the TSF] had been discussed loosely for a couple of years, and it really started when we committed to moving to the SEC,” Moller says. “Once that was a done deal, the comparisons to budgets around the league showed we had some work to do to catch up with our peers.”

Tiger Up

Associate Athletic Director Tim Stedman has attentive eyes. Even when he isn’t actively smiling, he naturally grins. His manner, beyond friendly, is calming and polished. When saying hello, he complements his handshake with a cordial pat on the shoulder. He doesn’t seem like one to engineer controversy, but perhaps that’s why Stedman’s job suits him so well.

Stedman oversees TSF operations for MU, and he’s the architect of the new format. He came to Columbia in 2010, drawn in by the opportunity to work for an athletic department ready to grow. And he hasn’t been disappointed. Still, he wants to spark something bigger.

opportunity to work for an athletic department ready to grow. And he hasn’t been disappointed. Still, he wants to spark something bigger.

“We built the new system around what we felt we could change,” Stedman says. “And change brings this bag of reactions, regardless of what the change is.”

In this case, the change is incentive. The previous TSF model, Stedman says, was too rigid. Donor benefits were too tightly tied to longevity: The longer you stayed in the system, the more “priority points” you accumulated, which was the determining factor in donor benefits, such as parking spots, seat locations and privileged information about Mizzou Athletics. There weren’t many options for donors looking to improve their standing, and there wasn’t an incentive to kick in more money. Even if someone donated more, he or she would be trumped by a longtime donor who had given less but accumulated more priority points.

MU’s tag for the new system, “donor level first,” reflects a change in philosophy. The new TSF model has 13 different donor levels, with donation thresholds ranging from $50 to $100,000. Your donor level determines what benefits package you get, and your priority points only determine your rank within your donor level.

For example, if someone donated $3,000, he or she would be in the Silver donor level, making the donor eligible for two parking passes. The donor’s priority points, which factor in donor longevity, would affect how good his or her spots in Silver parking were, but the donor would still be better off than everybody in the lower donor levels.

But a donor could easily leapfrog everyone else in his or her level, regardless of priority points, by donating money to get to the next level: a move that Stedman calls a “Tiger Up.”

“It all depends on how many people Tiger Up,” Stedman says. “We don’t have any way of predicting how much will change in terms of benefits, but people are looking to improve their donor experience and their game day experience, and now they have an opportunity to do that. That was the word we tried to message a lot: opportunity.”

The TSF brought in record donations in 2014: $23,600,149.74, to be exact. That’s nearly $5 million more than the previous record, set the year before. But if Stedman’s Tiger Up system works, as he expects it will, that record will swell.

The new model isn’t new, strictly speaking. The athletic department surveyed teams in the Big 12, the Big 10 and the SEC and found most comparably sized schools were already using a donor level-first system. MU’s model is largely based on Michigan State University, Stedman’s former employer. Six other SEC schools already use a similar format, including division rivals South Carolina, Vanderbilt, Tennessee and Florida, who raised the third most private dollars in the SEC.

Florida introduced the system 10 years ago. Phil Pharr, executive director of Florida’s booster club, says the switch initially disgruntled longtime donors.

“I don’t envy the position Mizzou is in,” Pharr says. “What you’re going to find out is that people say, ‘It’s only a good system if it’s good for me, and if it’s not good for me, then you’re an idiot.’ But it’s effective. It just took us a few years to find a comfort level with our fans.”

Doubtlessly, donors were cheerily distracted from their priority-point problems when Gator Football won two of the next three national championships.

“Winning makes it more palatable,” Pharr says. “If you want to sustain this level of success, you’re going to have to pay for it. Nothing in the business of sport is done on the cheap anymore. So you have to beat that drum but not too loudly.”

MU rolled out the new TSF amid palatable winning conditions. In its first three years in the SEC, the Tigers had won two division championships and added a $45.5 million club-seating wing to Memorial Stadium.

Both Pharr and Stedman used the Cold War metaphor of an “arms race” to describe SEC fundraising. A lack of money means fewer dollars spent on facility improvements, which usually translates to a weaker recruiting performance, which puts worse players on the field. Thus, bad fundraising begets bad teams, such as Vanderbilt, the only school trailing MU in private fundraising and owners of a 0-8 record against SEC opponents in 2014.

An SEC football team is a profitable business enterprise — Mizzou Football made $31.9 million in 2013, a budget surplus of $14.5 million — but the prevailing culture says schools have to spend money to make money. “Bottom line,” Pharr says, “Money will always trump longevity. Brick and mortar, new facilities, structural improvements: Those all take a hard dollar.”

Getting on board

The athletic department knew it faced an uphill battle with certain donors, so it got a running start.

The athletic department knew it faced an uphill battle with certain donors, so it got a running start.

“Anytime you’re changing points, donors are going to be interested,” Stedman says. “We’re excited about how we communicated with our donors and how they’ve received the change. We’ve tried to be as transparent as possible.”

This included personal meetings, newsletters, pamphlets, a website redesign, an animated YouTube video and as much grassroots campaigning as possible. The message, as Stedman says, was about opportunity and long-term benefits.

Thus far, the department has avoided public wrath. Although some donors are uneasy, most are confident that the university knows what it’s doing.

“I haven’t heard much backlash at all about it,” says Jeff Gregg, president of the Tiger Quarterback Club, the football team’s booster organization. “When you think about it, it’s good. It makes sense. It kind of dangles the carrot to make people want to up their donation level. People I thought might not like it haven’t said very much.”

The Quarterback Club, which provides its own member benefits, isn’t technically affiliated with the TSF, but the organizations overlap. According to Gregg and Kyle Bowers, president-elect, the core membership of the Quarterback Club consists of high-level TSF donors who take tradition seriously. To them, the game day society feels like home.

“We have loyal people that park in certain spots every week and come to tailgate every week because that’s just what they know,” Bowers says. “For some people, that’s just how they were raised — in parking lots. They have children now. I’m not joking, there are people who have been tailgating in the same spot for more than 30 years, and they have traditions.”

Despite palatable conditions and transparent communication, the consequences of the new TSF system are unavoidable. Some of these traditions will be moved around. “The big thing that’s going to come out is parking passes,” Bowers says. “When you’re tossing someone out of a lot, you’re messing with traditions, too. That’s going to be tough, and I’m not sure what’s going to happen.”

The TSF’s biggest hurdle is the future. Nobody — not the donors, not Stedman, not other SEC schools — knows exactly how much will change when the system takes effect in the 2016 season.

In redesigning its fundraising model, the university has reiterated its message: It wants to be an elite SEC school, and it needs more money to make it happen.

“There’s a cultural difference in the fanaticism between established SEC schools versus Missouri,” Gregg says. “As generations go on, we might get to that level, but you’re talking about 80 years of SEC religion in some of these places. That’s hard to overcome that in a 10-year period.”

The TSF is only a step in MU’s plan to change its sports culture. In doing so, it’ll have to change the world ingratiated within.