Bullets and box turtles

It’s not every day you go to work wearing a bulletproof vest and a hairnet, but for Kala Wekenborg-Tomka, who works with the Columbia/Boone County Public Health and Human Services Department, it’s just one more thing she did to get the job done. The environmental public health supervisor, then an environmental public health specialist, found herself potentially in harm’s way while doing a restaurant inspection at one particularly unsavory business several years ago.

It’s not every day you go to work wearing a bulletproof vest and a hairnet, but for Kala Wekenborg-Tomka, who works with the Columbia/Boone County Public Health and Human Services Department, it’s just one more thing she did to get the job done. The environmental public health supervisor, then an environmental public health specialist, found herself potentially in harm’s way while doing a restaurant inspection at one particularly unsavory business several years ago.

Peppers Nightclub, which was located on North Highway 763 and shuttered in 2011, was a hotspot for criminal activities, including shootings, stabbings, drug dealing and prostitution, says Boone County Sherriff Department Detective Tom O’Sullivan. “It wasn’t our primary concern whether or not they were complying with health code ordinances,” he says. “We were looking at their criminal activity — serious criminal activity.”

But according to state, city and county ordinances, because it was a food establishment, it had to be inspected. And because it was a medium-risk establishment — meaning, for example, it cooks and serves food but holds it for less than four hours — it had to be inspected without notice twice annually.

Wekenborg-Tomka did it with deputies in tow, with a Kevlar on for protection. “That’s the craziest inspection I’ve ever been on,” she says. “Honestly.”

Another time she walked into a different restaurant kitchen to see several box turtles crawling across the dish area. She ordered the creatures be removed from the premises. At another, there was a severe roach problem.

“The operators didn’t speak wonderful English,” she says. “And when we asked about their pest control record, the operators told us the roaches were on vacation and they’d be back next week.”

Sometimes, at temporary food events, Wekenborg-Tomka comes across food she isn’t familiar with. “You see some crazy stuff that people cook, unusual,” she says. “You can’t really identify it, and you don’t really know what it is. They can’t tell you where it came from, and so it needs to go.”

Backed by science

To be an environmental public health specialist in Columbia/Boone County, one needs, at minimum, a bachelor’s degree in science, with at least 30 hours in the biological sciences. Wekenborg-Tomka, who has been with the department since 2001, has a degree in animal science. She also has a master’s in health administration.

“There is a lot of microbiology that you do need to apply,” she says.

The eight people on staff routinely monitor 800-plus food establishments, which include everything from day care facilities, to gas stations selling sandwiches, to chains such Burger King, to full sit-down restaurants. They’re broken into three categories: low, medium and high priority. Low priority is a place such as a convenience store that doesn’t make sandwiches on the premises but rather cold-holds them. Medium-priority eateries are establishments such as sandwich shops that make soups but toss them at the end of the day instead of reheating them for further consumption. High-priority establishments have more complex steps and are usually sit-down restaurants.

Low-priority establishments are inspected twice a year. Medium and high are inspected three times a year minimum in Columbia; medium-priority establishments in Boone County are inspected two times minimum. Inspection times vary from a half hour for a low-priority establishment to an hour or more for medium- to high-priority businesses.

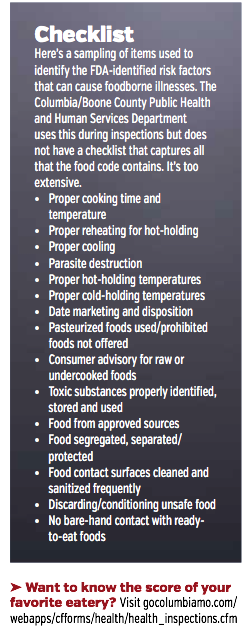

“What do we look for?” Wekenborg-Tomka asks. “Our inspection is based off of science, based off of code. We use the 2009 [Food and Drug Administration] model food code for our foundation, basically, to conduct these inspections. The FDA establishes the code based on science in conjunction with the regulatory industry and also academia, so it’s really highly science driven.”

She says it’s not her goal to give as many citations as possible. Rather, she aims to identify risk factors that lead to foodborne illness and educate operators to ensure unsafe practices are changed to eliminate risk factors.

Write-ups for safety

Citations are broken into two categories: critical and noncritical. Critical citations include things such as no soap in hand sink, employee drinks without lids, unlabeled spray bottles, unclean food contact surfaces, temperature violations, soiled ice scoops, improper hand washing, weak sanitizer, cracked spatula and soiled pans. Noncritical items include the likes of nats present, Red Bull cans in the drink ice, unshielded lighting in kitchen, wiping cloth not stored in sanitizer, soiled microwave handle, sugar bucket not 6 inches off the floor and food not in food-grade bags.

For critical items, corrections have to be made in three days, though sometimes they are corrected at the time of inspection. Noncritical items are addressed at the next inspection.

“We have temporarily closed establishments due to violations,” Wekenborg-Tomka says. “For example, if there’s no water, you can’t operate. That’s a pretty serious health hazard.”

Usually, business closures are based on formula. For a high-priority business to be temporarily closed, it has to have 10 critical violations, 20 noncritical violations or a combination of 25 violations. For a medium-priority business to be closed, it’s eight critical,16 noncritical or a combination of 20 total. For a low, it’s six critical, 12 noncritical or a combination of 15 total.

To operate a business, you also have to have a food handler’s card. To get it, the owner attends a one-hour class. The class is offered four times a month: two day and two evening offerings. The card is good for three years.

Language barriers can sometimes be a problem, Wekenborg-Tomka says, both in the classroom and inspection setting.

“We continue to try to improve our services to be able to serve all our customers,” she says. For example, the department now offers training, both audio and visual, in English, Spanish, Korean, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Tagalog and American Sign Language.

Funding for that and other projects, such as having the ability to do food-safety inspections on an iPad, is provided through a five-year FDA grant that gives $70,000 a year for five years. They are in year three of the grant.

“We’re excited to be able to allow folks to come in and listen to a presentation in their native language as well as possibly read it and then take an exam in audio and visual format as well,” Wekenborg-Tomka says.

At Chris McD’s on Forum Boulevard, owner Chris McDonnell welcomes the inspection process. “I think it’s a must,” he says. “We try to get a zero every time, and it’s very hard.”

He says their inspector usually comes during the busy mealtime versus prep time. Inspections come every three months, and he is now due for another.

“It’s an ongoing process,” he says. “It’s every day. Every day you’re checking temps. You’re watching handling. You cannot have a problem; it’s just not optional. I think the public needs to feel safe when they go to a restaurant, know someone is watching.”