A Taste of Nuclear Medicine

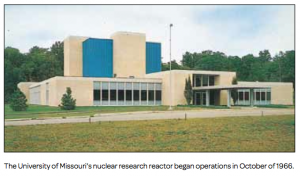

The most exciting development on the University of Missouri campus these days is using the research reactor to produce medical isotopes for the treatment of patients afflicted with various forms of cancer. Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin wants to make the Columbia campus preeminent in this field uniting the reactor with University Hospital and Clinics, the Ellis Fischel Cancer Hospital and the recently announced alliance with the M.D. Anderson Clinics in Texas and Florida.

The most exciting development on the University of Missouri campus these days is using the research reactor to produce medical isotopes for the treatment of patients afflicted with various forms of cancer. Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin wants to make the Columbia campus preeminent in this field uniting the reactor with University Hospital and Clinics, the Ellis Fischel Cancer Hospital and the recently announced alliance with the M.D. Anderson Clinics in Texas and Florida.

This would cement Columbia’s position as a key medical destination with the potential to attract cancer patients from all over the world. Yet, Columbia Regional Airport is still a municipal embarrassment.

Loftin then startled us with his plan to build a small hospital adjacent to the reactor. Given the comparatively short temporal life of certain medical isotopes, the concept of a small hospital next to the reactor is to reduce transit time for these materials moving from the reactor facility to the patient needing them. Loftin’s idea to build a small hospital specializing exclusively in nuclear medicine has been mentioned several times by the chancellor. Brought up recently in discourse with a member of the Columbia City Council, the representative says it was the first he’d heard of this novel and rather significant proposal.

While a small cabal of community activists and City Council members beat the tom-toms for slow growth, “smart” growth — whatever that is — or no growth at all in the case of one council person, plans to hike development fees and institute trip generation levies grab the headlines. This group’s glaring ignorance of MU’s plans and forward drive to a unique world-class position in nuclear medicine and the potentially groundbreaking treatment of cancer patients is downright hurtful if not scandalous. How ironic it is that members of this maliciously meddlesome crowd have the nerve to worry about public attitudes toward the city when they, themselves, may be responsible for initiating some, if not all, of the gloom and doom they appear to be fretting about?

Meanwhile some of the once scowling 14,000 Columbia Water and Light customers affected by the late evening windstorm on July 7 have probably reevaluated their attitudes about the department while almost universally praising the diligent efforts of crews who worked tirelessly to restore electrical service. Aside from the Southridge tornado on Nov. 9 and 10, 1998, the last major storm to inflict significant damage and widespread power outages across Columbia arrived shortly before 2 p.m. Monday, July 20, 1981. Winds were clocked at up to 77 miles an hour, more than 10,000 customers lost power and damage estimates passed into seven figures. In both storms, some customers had no power for 60, 70 and 80 hours, and the outages were most significant where lines passed through heavily wooded areas.

For some, this may bring about the evaluation and subsequent installation of a backup power system typically fueled by natural or LP gas. Without casting aspersions on the generally exemplary performance of the Columbia Water and Light Department over the years, backup power may still be called for if there are reliability issues or the home or business requires a fault-free, uninterrupted supply of electricity. As for widespread outages in the recent storm that affected hundreds of homes in neighborhoods encased in verdant growth, a more aggressive trimming program would seem to be in order. The department should also hone its communication skills, perhaps with a running commentary on its website describing where crews are working and giving estimates of when service will be restored.

Thrust into sudden darkness shortly before midnight when the storm doused the lights in a familiar setting conjures up thoughts of self-preservation if one is unlucky to be where the surroundings are less familiar. The first move is to equip oneself with a small flashlight. Reviewing the history of disasters in crowded public places leads to the same conclusion: Sudden darkness typically begets tragedy and major loss of life. Many of the more than 600 people who died in the Dec. 30, 1903, fire in Chicago’s Iroquois Theatre might have been saved if the house lights had been turned back on during a darkened scene in Mr. Bluebeard. The Nov. 28, 1942, holocaust that cost the lives of 492 patrons in Boston’s Coconut Grove nightclub where the lights went out led Massachusetts followed by other states to mandate the installation of emergency lighting in all public places.