Innovating for the Animal Kingdom

The University of Missouri is known for many things. When it comes to fields of study, conversation more often than not revolves around the journalism school. In sports, it’s the SEC. In the music and entertainment world: Sheryl Crow, Brad Pitt or Chris Cooper. And in the business sector, it’s Sam Walton.

What you might not realize is the impact MU has had on the animal kingdom, well beyond its mascot, Truman the Tiger. Inventions keep springing up from the halls and labs of the College of Veterinary Medicine, where a few instructors with the entrepreneurial bug have taken their research to a whole new level.

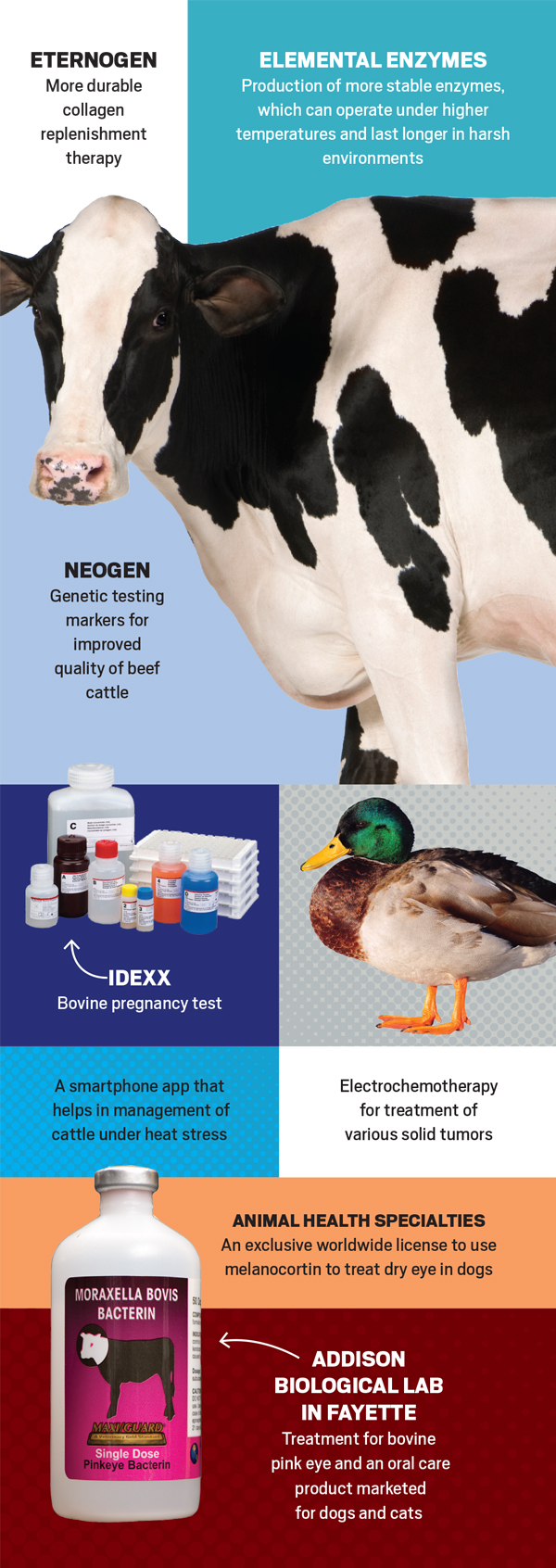

Researchers at MU are responsible for many animal health products on the market today. Some of these include the use of a computer tablet and sensors to detect where a horse may be hurting, the prevention of pink eye in cattle, acceleration of an animal’s immune system and a oral cleansing gel for dogs.

Going from a big idea to a business is no small task. It takes an enormous amount of networking, persistence and funding. The good news for entrepreneurs in mid-Missouri is a culture dedicated to making those dreams reality. The Missouri Innovation Center plays a big role in this effort. Under its auspices, the Life Sciences Business Incubator opened five years ago to help companies develop viable ideas. The incubator rents lab space near the university’s football facilities and MU’s nuclear reactor.

Jake Halliday, CEO of the Innovation Center, said the 20-plus companies at the Incubator are thriving in a market conducive for entrepreneurship. “In Columbia, we have all the elements of the infrastructure you need to launch high-tech ventures,” he said. “We have physical lab space and legal, regulatory, and grant-writing support. It’s not Boston, but it’s a nice-sized community that has everything you need to get going.”

One of the companies operating out of the Incubator is Equinosis, makers of the Lameness Locator, an increasingly popular system among veterinarians across the country. Its founder is Dr. Kevin Keegan, a professor of equine surgery at MU’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

The system identifies lameness in a horse via electronic monitors placed at several points on the animal. The monitors transmit data wirelessly to a computer, which can detect any irregular or uneven body movement. What makes it unique is that it measures the energy of the vertical motion of the horse’s torso rather than observing the gait with the naked eye, which has been the traditional method for determining lameness.

A U.S. patent for the system contains the names of three men with connections to MU. Besides Keegan, the other creators are Dr. P. Frank Pai and Dr. Yoshiharu Yonezawa. Pai is a professor in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at MU, and Yonezawa had worked at the university in years prior.

A U.S. patent for the system contains the names of three men with connections to MU. Besides Keegan, the other creators are Dr. P. Frank Pai and Dr. Yoshiharu Yonezawa. Pai is a professor in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at MU, and Yonezawa had worked at the university in years prior.

Keegan says their creation, which is now being used in about 140 locations across the United States, was more of an evolution than a single concoction in a lab.

In the 1990s, Keegan put horses on treadmills and used high-speed cameras to complement the subjective evaluation of lameness. He teamed up with Pai to develop a way to measure a horse’s movement. Then came the chance meeting that would change everything.

A colleague encouraged him to attend a conference in Colorado put on by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. “It was strange that a veterinarian would go to a conference full of engineers,” he says. While there, Yonezawa, a Japanese engineer from the Hiroshima Institute of Technology, approached him.

“He noticed I was from Columbia, which is where he had come many years ago to do a post-doctorate,” Keegan says. Keegan shared his work and the science behind it. Yonezawa was all in.

“I supplied the horses and the idea, Dr. Pai pioneered the algorithms, and Dr. Yonezawa made the sensors,” Keegan says.

Their ideas would need significant financial backing for them to progress from their lab to nationwide vet clinics. A local angel investment group, Centennial Investors, provided early money, which was then used to apply for more funding. They received an initial grant from the National Science Foundation’s Small Business Technology Transfer Program. “From there we sold prototypes, got matching funds and then sold more prototypes,” Keegan says. “It has been a good process, and we have generated more revenue than funding, so we’re in the black.”

Financial partners and translational research

Investing money in a startup is not as easy as meeting up, pitching an idea and walking away with a big check. “If it’s an idea we really want to pursue, we’ll start peeling back layers of the onion, looking at their financials, intellectual property, competition and claims,” says Bruce Walker, president of Centennial Investors, a local angel investing group that provides funding for early-stage enterprises. “If it passes our tests, then members who are interested will ante up, typically $7,500 to $10,000 each.” Walker says the range of their startup funding is from $150,000 to just more than half a million dollars.

Centennial Investors has early funding to several successful startups, but every once in a while, companies decide to expand to other areas, such as Immunophotonics (cancer therapies).

“Companies may have another medical partner in a different city,” Walker says, offering a reason for local departures. “They sometimes feel the need to move where the venture capital is.” After startups get some measure of funding, programs will begin holding competitions for grant money. Nonprofit Arch Grants of St. Louis has already provided almost $2 million to 35 programs, including a $50,000 check to Immunophotonics. Although their funding is fairly small, Arch Grants touts its relatively easy application process as an attractive draw for entrepreneurs; it does not take equity from firms and only requires startups to have a presence in St. Louis.

Walker, who also served as dean of MU’s Business School for 20 years, says he’s seeing much more local support for commercializing inventions. “There’s a real culture of entrepreneurial support in Columbia.”

Keegan agrees, though he says the environment in Columbia was challenging at first. For example, the first NSF grant required the primary investigator for a startup to be employed by the business concern. “I couldn’t leave my university job, so it was rough at first.” But the university, he says, was gracious enough to allow him to take a sabbatical so he could focus on the project. “The administration has been very open.”

Carolyn Henry, a veterinary oncologist at MU, says she sees a positive level of collaboration on the MU campus. “We now have curriculum related to entrepreneurship and a culture that encourages multidiscilinary, translational research and development,” she says. Translational refers to treatments for animals that hold promise for crossing over and benefiting humans. An example is Henry’s own study of drug development for anticancer therapies. She has worked with a radiopharmaceutical compound originally developed in Columbia that was used on dogs with bone cancer. Dow Chemical eventually developed it as a therapy for human cancer patients under the name Quadrant.

In addition, MU’s College of Veterinary Medicine was one of the institutions that carried out the pivotal trial for approval of the drug Palladia, the first ever FDA-approved anticancer therapy for dogs.

More evidence of the collaboration of translational research and development in Columbia is the fact that Henry helps direct research at Columbia’s Ellis Fischel Cancer Center.

Although most undergraduates look to start their own private practice, a spirit of entrepreneurship is also rising within the student ranks. Henry says they have recognized the need to provide students with exposure to alternative career options.

The college’s small animal clinic has an oncology clinical trials service separate from its typical trials service. “Students learn what is truly involved in conducting clinical research to the level of quality that will result in products making it through the approval process and to the health care market,” Henry says. “The typical barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship are simply being pushed aside by the energy on this campus.”

The serious focus on merging the talent of academia with business can also be seen in the number of area partnerships. You can count on one hand the number of universities in America that house a school of medicine, veterinary medicine, engineering, agriculture and law all on the same campus. When colleagues at these schools interact, innovations result. By the time you add the support of local Regional Economic Development Inc., the Columbia Chamber, angel investors and the Life Sciences Incubator, you have acquired significant momentum.

It also helps that mid-Missouri has the prestigious Kansas City Animal Health Corridor, the stretch between Columbia and Kansas City housing firms specializing in animal health nutrition, innovation and production. The KC animal health and nutrition industry accounts for nearly one-third of the total sales in the global animal health market.

The animal health corridor was a great bonus for Bruce Addison, founder of Addison Biological Laboratory. The longtime Missouri resident wanted to remain in the state, and he got his wish; most of his clients are within a few hundred miles of his operation in Fayette. In addition, they export products to more than 25 countries around the world.

Addison counts himself blessed to have the College of Veterinary Medicine within a small commute from his operations. “When I’m on a research project, I can pay bright and talented people right there [at the college], instead of having to hire somebody outside, bring them in, only to see them leave,” he says. “You can solve a lot of problems and make a lot of breakthroughs here in mid-Missouri with the talent we have.”

The company is perhaps best known for its licensed vaccine for bovine pink eye, a product Addison himself invented that stems from his research in graduate school.

Addison Labs is one of the older vet technology companies in the area. It has learned what it takes to survive the economic upswings and downturns for the past three decades. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce selected it for the prestigious Regional Blue Chip Enterprise Initiative Award, and last year the Missouri Chamber selected Addison’s company as a Fast Track Award winner, which recognizes the fastest-growing companies in Missouri over the past three years. “Sometimes you get lucky,” Addison says.

It’s luck, perhaps, and a lot of investment. Aside from financial help from private investors, Addison kept his nose to the grindstone to get his company up and running. “I spent the first seven years working 90 hours a week,” he says. “A lot of people will tell you that you can’t do it, but if you listen to them, you might as well work for someone else.”

Another very successful product for Addison is the Maxi/Guard Oral Cleansing Gel for dogs and cats. Many dogs by the age of 3 have developed significant gingivitis. Addison says the overwhelming majority of owners just don’t think to brush their dogs’ teeth on a regular basis, which can shorten the lifespan of their pets.

The oral care product had its roots at the University School of Medicine, where Addison was working as a microbiologist and part of a research team. While they were working on a mouthwash for people, Addison began thinking toward an animal solution. “I figured a spray wouldn’t be effective for dogs because it would get in their face,” he says. So they developed a gel. Its success has been incredible. One story is of toy dog bred in Dallas that, after going on a daily application of the product, went beyond a year without needing its teeth cleaned.

The application is relatively simple: Put a drop on your finger, and apply it on each side of the dog’s mouth. “When dogs usually undergo traditional oral treatments, they don’t sit in a chair and listen to you talk,” he says. “They have to be put under general anesthesia, which scares a lot of pet owners. With this product, you don’t have to worry about that.”

Nose to the grindstone

One thing aspiring entrepreneurs need to be aware of, Addison says, is the cost associated with going to market. He reiterated the need for angel investing by groups such as Centennial Investors to get projects off the ground.

“It took four years and $2 million to license our original pink eye vaccine,” he says. “Federal regulations and pricing continue to increase, and what used to take six months to realize now takes five years.”

That hasn’t stopped Addison’s group from plowing ahead though. More products seem to be on the way. They recently returned from a Las Vegas conference and had sales meetings with representatives from Japan, Britain and Brazil.

Keegan also has advice for those getting into startups. One must balance the promise and pitfalls and be diligent. “You have to have a strong family because it’s very difficult,” he says. “You have to surround yourself with people who are facilitators and get rid of people who are obstructionists.”