International Game

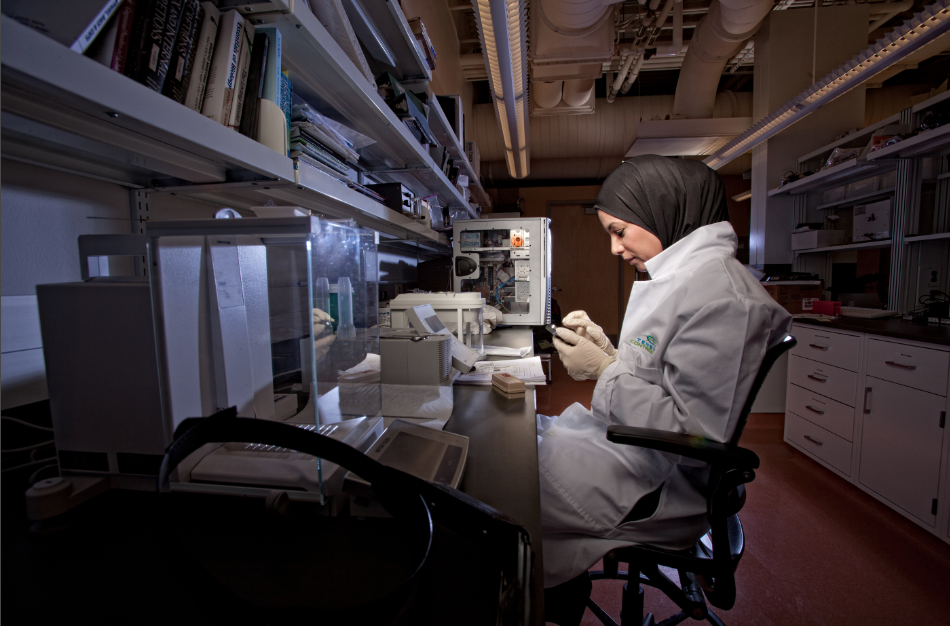

Approximately 6,516 miles separate Amman, Jordan, and Columbia. Penelope Shihab, CEO of Jordan-based MONOJO Biotech, is determined to bridge that gap. She has created an offshoot of her company called Columbia Biotech, which launched its Skinue cosmetic line last month; the products are already available online.

The process, however, was far from simple. A variety of factors threatened to restrict Shihab’s success: a traditional culture that does not encourage female entrepreneurs, a lack of funding, a balance between work and family and the ability to create an international brand. Still, she has a far loftier goal in mind: pharmaceuticals for acne and gastritis, which is stomach inflammation caused by stomach ulcers, among other things. Pharmaceutical drugs can take years and millions of dollars to get to market, mostly because of rigorous regulatory standards, so the cosmetic line will serve as a bridge to the ultimate goal.

“In the U.S., you just can’t do this quickly,” Shihab says. “But the Skinue line still has effective products with the active ingredient for skin nourishing.”

Shihab hopes to extend her products’ market to the Middle East and other countries after her venture into the U.S. market. Beyond the tough regulations in the United States, Shihab also has to balance scientific research and entrepreneurship while raising four children with her husband. And she is pursuing a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge.

CoMO connection

The first question that might come to your mind is: Why would an international biotech company use Columbia as a launch pad? The first answer to this question is that Columbia houses the MU Life Science Business Incubator. The incubator takes a well-developed innovation and fosters relationships with entrepreneurs to make it marketable. Although this commonly happens using the patents and products of university professors, the incubator is open to other entrepreneurs as well. As Shihab searched for necessary resources, the incubator fit the bill.

“We have gone out of our way to develop services uniquely focused on overseas companies coming to the U.S. market since almost any technology company will ultimately look at the U.S.,” says Jake Halliday, president and CEO of the business incubator. The incubator uses a full-cycle technology commercialization program, which involves coaching from the time the innovation or product is developed until placement in the marketplace.

For Shihab’s business goals, Halliday says the incubator uses a complex sequential strategy. This means the goal is “finding a pathway to revenue relatively quickly while also having longer development products,” he says.

But long before Shihab knew of the incubator’s resources, she started with a list of qualifications her company needed to be successful, such as a large market, good selling environment, talented people for her team, access to other entrepreneurs and funding resources. All of these happened to be in the United States, so she took the leap into unexplored territory and set her sights on launching her products in the United States.

“I started my journey with no money and little support, but it was a dream I wanted to come true,” she says.

Her dream came one step closer when Samih Darwazah, founder of Jordan-based Hickma Pharmaceuticals, decided to back MONOJO. Darwazah is a graduate of the St. Louis College of Pharmacy and directed Shihab to resources in Missouri. Shihab says he recommended Missouri because of the availability of an accessible market, as big markets are tough to get into with little experience.

Shihab’s success has spun out of a series of vital international connections. She became close with Cambridge professor Chris Lowe of the university’s Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology after they met at a conference. Both Lowe and Shihab joke about her incessant emails and persistent spirit.

“She’s very pushy when she gets going, believe me, and that’s where motivation comes in,” Lowe says. “She actually gets things done, and in the country she comes from, it’s a damn difficult thing to do.”

Lowe has visited the MONOJO headquarters and supervises Shihab’s doctoral work in addition to helping develop MONOJO since he met her in 2006:

“I do tons of interviews at the university for what we consider to be the top people in the world,” he says. “A main thing I look for is motivation. You get maybe 10 out of 2,000 that have the degree of motivation she has. That’s why I back her and why I continue to back her.”

Over the past year and a half, Shihab has researched the Columbia market and its members, which has allowed the community to get a sense of her product and spirit. After this market research, Shihab developed relationships with Missouri School of Journalism students who then developed a three-month plan for increasing her community presence. The first phase of the plan involved branding Shihab in addition to her cosmetic line and emphasizing her unique role as a woman, a Cambridge student and a passionate entrepreneur, so she began to talk about the brand anywhere and everywhere. Next, she implemented a social media presence, reaching out through Facebook and updating her website. Finally, she sent samples of her products to media and retailers to receive feedback before the products were on the shelves.

Camel what?

After Shihab found interested investors, located to Columbia for a soft landing and decided on a product line to begin her American launch, she had to decide if Americans would actually take a leap of faith and buy her product. The main ingredient, camel’s milk, is far from common in the United States, and Shihab had her worries about whether the product would be considered too exotic.

However, she found through surveys and interviews that the camel’s milk would not be a problem. “After my studies, I was sure that my market liked the brand and would buy it,” Shihab says. “This was necessary so I felt comfortable going to another state and expanding.”

Lowe says the local Bedouin tribes in Jordan have been using the camel’s milk regularly for the treatment of various ills, and the folklore surrounding it seems to intrigue people. “The milk isn’t dangerous, but there’s intrigue in the fact that it was camel milk,” Lowe says. “Everyone asks, ‘Why camel milk, and what’s so special about it?’”

Well, MONOJO has found there are legitimate medical uses for the product. “Camel antibodies are very stable under fairly harsh conditions,” Lowe says. “If you inject another antibody into the stomach for an ulcer, it would be almost immediately disintegrated, but the camel antibodies survive.”

This resiliency seems to mirror MONOJO’s fearless leader, Shihab. She emphasizes in working on the gastritis and acne pharmaceuticals because she “won’t do science just for the sake of science.” UNESCO reports approximately 50 percent of graduates who earn science degrees in Jordan are women, but Shihab says far too much of this work is purely academic.

“I want to create more jobs and raise the profile of the women in Jordan and Arab countries,” she says. “I want to be a role model despite little support from the government; we just don’t need more scientists without any production.”

Paving a way

The reality of being a woman, especially in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), can come bearing various obstacles: scheduling difficulties, lack of time for a family, less pay for equal work and myriad statistics against your success. But the story of Penelope Shihab shouldn’t be an anomaly.

Although some companies are on their way to creating more opportunities for flexibility in the workplace for women with families, a recent study shows women are dropping out of STEM fields because they find the environment “inhospitable.”

According to research from Cornell University and the University of Texas at Austin, these women leave their fields of specialty at a rate much higher than other professional women. More surprisingly, this tends to happen early in their careers. “A lot of people still think it’s having children that leads to STEM women’s exits,” says Cornell professor and study leader Sharon Sassler. “It’s not the family. Women leave before they have children or even get married. Our findings suggest that there is something unique about the STEM climate that results in women leaving.”

In addition to mentorship from the beginning of the commercialization of her company, mentors such as Lowe have embraced Shihab being a model for Arabic women.

“She shows all of those women in tradition roles as housewives that they can also be successful at other things,” Lowe says, “and we’ll be doing our bit if we can help her reach her goals.”