MU, city consider retirement system overhauls

The financial crisis has caused the University of Missouri System and the city of Columbia to consider revamping their pension systems.

The university wants to shift the risk of its retirement fund to employees through individual retirement accounts. The city, to shore up its fund, will likely ask employees to contribute more to the pension plan or increase the retirement age.

As the Columbia area’s largest and fifth-largest employers, what the university and city eventually decide will affect thousands of workers and the amount of money future retirees pump into the local economy.

Both the city and the university offer defined benefit retirement plans, which promise a check to retirees until they die. Those checks are usually based on average salary and years worked for the institution.

Current employees would keep their accrued pensions; the change to defined contribution plans would apply to future employees, though contributions could rise for current employees.

Investment returns from funds managed by the institution pay for the majority of retirement obligations. That worked out well when markets were booming, but after the financial shocks of the past several years, each entity has had to make up for shortfalls by kicking in an increasing amount of its own cash. Strained budgets at all levels of government make it that much harder to meet the shortfalls.

“Baby boomers began retiring at exactly the time we’ve had two historic declines in the investment market,” said Steve Yoakum, who heads Missouri’s public education employee pension fund and was recently tapped to chair a task force examining the city’s funds. “Literally, those two things happening simultaneously is the perfect storm.”

The discussions in Columbia are not unique. Many universities and businesses as well as some cities have already moved to defined contribution plans. And public pension funds everywhere have been hit by both a bad market and budget shortfalls, which makes it more difficult to meet the extra funding necessary to keep the plans solvent.

The state of Missouri changed its employee pension fund rules this summer. New employees must contribute 4 percent of their salaries to the fund (employees didn’t contribute before), and the retirement age increased. The University of California’s pension plan has $21 billion in unfunded liabilities. Pittsburgh has only 28 percent of its pension liabilities funded, and the state of Pennsylvania might take over the fund by the end of the year if the city can’t cover more of

its obligations.

Those are just some of the most extreme examples. But the city of Columbia is still struggling to meet the increased costs of its pension plans during a time of stagnant revenue. In September, Mayor Bob McDavid appointed a special task force to study the city’s pension plans and develop options to deal with the fund’s growing liabilities.

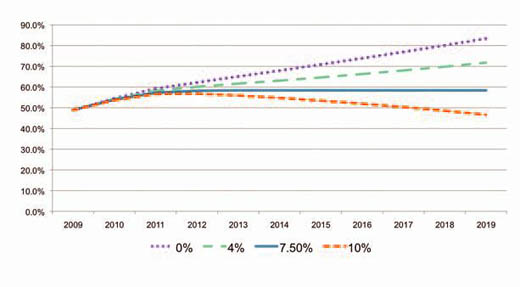

Those liabilities stand at $255 million right now, with the funds’ assets only worth around 65 percent of that. The city’s liabilities have the potential to grow to $464 million by 2019 and $1.57 billion by 2039, according to a report from Yoakum.

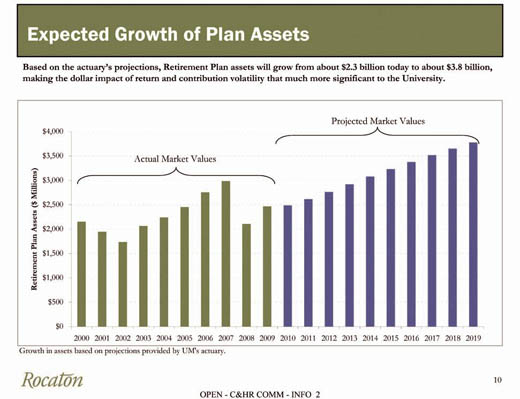

The University of Missouri began to discuss changing its retirement plan more than a year ago. With 96 percent of its liabilities funded, the fund is in very good health relative to its peers. Still, the market value of its assets dropped from almost $3 billion in 2007 to about $2.5 billion as of Oct. 1.

The university’s fund is expected to grow to about $3.8 billion by 2019, and administrators are concerned about the uncertainty of future payouts. The city faces the same issue: Uncertainty about investment returns, and thus employer contributions, becomes more pronounced as each fund grows larger.

Neither institution has a definitive plan for overhauling its retirement funds, but the health of the two funds is critically important for both the institutions and the region.

More than a year ago, the University of Missouri began discussing a none-too-novel retirement plan change. Administrators want to switch from a defined benefit plan to a defined contribution plan. Similar to a 401(k), defined contribution plans allow individual employees to save a certain amount of their paycheck, often supplemented by employer contributions, in an investment account. The individual is then responsible for saving enough for retirement and putting his or her money into investments that will generate sufficient returns.

In the university’s case, such a move would actually increase the cost in the short term because the existing defined benefit plan would remain in place. But university administrators say the switch is necessary to lower the institution’s liability and reduce uncertainty over future costs. Such a switch essentially shifts market risk from an institution to an individual.

“The trouble is when you have these (defined benefit) plans, you’re making promises that are way out there in the future, and you don’t really know whether you can deliver on these promises,” said Glenn MacDonald, an economist at Washington University in St. Louis who studies business strategy and compensation.

The proposed shift at the university is one that has been ongoing for years. Defined benefit plans are a “relic,” MacDonald said, and private industry has been moving away from them for decades.

The trend has been accelerating in recent years. 3M stopped offering defined benefit pensions to new employees last year. IBM froze its defined benefit plan in 2006. Out-of-control pension costs contributed to GM’s and Chrysler’s bankruptcies, and all the Big Three automakers stopped offering defined benefit plans to new employees in 2007.

According to data compiled by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, the percentage of US workers covered by only a defined benefit plan fell from 62 percent in 1983 to 17 percent in 2007. Conversely, the proportion of workers enrolled in defined contribution plans rose from 12 percent in 1983 to 63 percent in 2007.

Pensions made a lot more sense 50 years ago, when people tended to stay with one job most of their lives, MacDonald said. Now, on average, people hold close to 10 different jobs. A 401(k) can be moved from job to job, which makes it more attractive to younger employees who don’t necessarily plan to stay in the same spot for 35 years.

“In part, MU is not only dealing with its own budget realities, but also the competitive realities of hiring young and mid-level faculty,” said Joe Haslag, an economics professor at MU.

Contributing to the trend is the increasing accessibility of financial markets. In the middle of the 20th century, many people didn’t want to deal with investments, and they preferred a defined benefit package, MacDonald said. Investing is much easier these days, and people are less mystified by the markets.

“In your grandparents’ generation, most people really didn’t have investments,” MacDonald said. “There was no Vanguard. There were no diversified mutual funds. If you wanted to have assets, you had to have a stockbroker.”

Downsides of defined contribution

Critics of defined contribution plans, however, say that people often don’t save enough for retirement, draw down their retirement accounts too quickly and don’t allocate their assets as wisely as professional pension fund managers.

A 2009 study by the US Social Security Administration found that if defined contribution plans replaced defined benefit plans for people born from 1961 to 1965, 11 percent would retire with more money and 26 percent would have lower family incomes.

“On balance, there would be more losers than winners, and average family incomes would decline,” the study’s authors wrote.

Nancy Hwa of the Pension Rights Center, a Washington-based group that lobbies for defined benefit plans, said people weren’t too worried about their defined contribution plans while financial markets were consistently making double-digit returns.

“The recent recession was a big wake-up call for people with only defined contribution plans because they saw their account balances plummet,” she said.

Defined benefit plans are also more efficient than individual defined contribution plans, Yoakum said.

“There’s no question that it’s a better, more effective generator of benefits,” he said. “More bang for your buck. But there is risk, either for taxpayers or shareholders.”

Yoakum agrees with the concerns of those defending defined benefit plans. There is evidence that indicates people don’t save enough for retirement, don’t manage their savings well or spend it too quickly, he said.

“Control your own retirement: It’s a lovely sounding thing,” Yoakum said. “But do you really want them to do it? You may end up paying them in public welfare rather then having them pay for their own retirement.”

But MacDonald said the data doesn’t back up those concerns. Haslag agrees and said people are more than capable of planning for their future.

“To say that people are systematically stupid really bothers me,” Haslag said. “I think people make very complex decisions looking forward.”

The debate at the university is over who should bear the risk of retirement liabilities: the institution or the individual.

At a board of curators meeting Nov. 1, Rod Crane, senior director of government and religious markets for TIAA-CREF, said median return for public pension funds had been 8 percent. But in the past 10 years, that has fallen to about 6 percent. The question is whether the 8 percent assumption is realistic going forward.

Curator David Wasinger said at the meeting that the “private sector has adapted” and that the university’s future contributions to its pension funds will ultimately be funded by tuition increases.

“I almost see it as a fiduciary obligation on our part to take some kind of action,” he said.

Curator Wayne Goode, however, was skeptical about putting the entirety of retirement planning up to individuals.

“At least part of the money should be professionally managed similar to how our plan has been managed,” he said. “If you give an employee total flexibility, some of them are going to really screw it up.”

Allen Hahn, chairman of MU’s Retiree, Health and Other Benefits Advisory Committee, said many older faculty and staff are skeptical of the possible switch and its possible effect on recruitment. Young faculty, though, are less concerned, he said.

Because the fund has been so well managed, Hahn is not convinced a change is necessary.

“I think the common knowledge is, well, everybody’s doing a defined contribution program, so we ought to do the same thing,” Hahn said. “And I think, in my opinion, we haven’t really proven that case yet.”

Curator Warren Erdman said at the curator’s meeting that the university is trying to be proactive rather than “kicking the can down the road.”

“We’re trying to exercise an extra degree of prudence,” he said.

A presentation at the meeting by Betsy Rodriguez, UM vice president of human resources, detailed retirement plans at peer institutions in the Big 12 and Big 10. All of them offered either a defined contribution plan only or a choice between that or a defined benefit plan. Only Missouri offered solely a defined

benefit plan.

Missouri would be following the trend if it switches, Haslag said.

“Higher ed seems to have moved more toward defined contribution plans more like private industry than, say, a lot of other government agencies have,” he said.

The city has a more immediate problem. All of the money Columbia pays to shore up its retirement plans comes out of its general fund, which leaves less money to go toward other services. And the funds need more shoring up than ever after the 2008-2009 market downturn.

Columbia manages its firefighter and police pensions, which have combined unfunded liabilities of $54.6 million. These funds demand the most immediate attention, Yoakum said. The police fund is about 63 percent funded, and the firefighter fund is about 61 percent funded. To meet obligations for the police pension, the city will pay 34 percent of fiscal 2011 police payroll into the fund. For the fire pension, the city will have to contribute 48 percent of payroll.

The city’s other employees are covered by the Local Government Employees Retirement System. One fund covers city utility workers, and another covers the rest. Although those are only 62 percent and 74 percent funded, respectively, they are in much better shape. The city will only have to contribute about 16 percent of payroll to cover each fund’s obligations.

A study from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College examined a sample of 126 pension plans. It found that in 2009, only 78 percent of all the funds’ liabilities were covered — a $700 billion shortfall. The industry benchmark for a well-funded public plan is 80 percent. Only 10 years ago, before the tech bubble popped, public funds were 103 percent funded, the study’s authors found.

The future health of public plans depends mostly on the performance of the stock market, and the Boston College study asserts that the most likely outcome is that funding ratios will decline to 72 percent by 2013.

What the markets will do is an ongoing debate among the people who manage pension funds. Some wonder whether current conditions are a new normal. If that is the case, the lower returns mean institutions will have to significantly increase the money they contribute.

“There are a lot of people thinking that this low return is a new normal kind of environment,” Yoakum said. “What one has to say is, don’t get overly concerned about the short run. … Is that the new return, or are we in a period that’s just unusual?”

Columbia Finance Director Lori Fleming noted that though the city made all of the contributions required by its actuaries, it was still chasing a liabilities curve made steeper by increasing retirements and longer lifespans.

“Even if we earn 10 percent (from the fund’s investments), our liabilities are growing faster than our contributions,” Fleming said. “Part of this is the demographics of it. People are living longer. It’s not just a rate-of-return issue.”

Institutions making pension promises know there will be fluctuations in the market, MacDonald said. If you’re depending on an 8 percent return from the markets, you better be putting away extra for when those returns dip below that. Pension funds didn’t do that when markets were booming 20 years ago, he said.

“They always act like there’s never going to be a rainy day,” MacDonald said. “Every time anything good happens, they merrily spend the money. And any time anything bad happens, they’re stuck. For the most part, it’s really just bad planning.”

Public funds have a difficult hurdle going forward, Yoakum said, but he thinks it’s one they have to jump. Defined benefit pensions can serve public institutions better than defined contribution plans because they reduce employee turnover, he said. The public sector can’t offer the salary the private sector can, but they can hold onto employees with a benefit that requires a worker to stay with the same job.

Columbia Human Resources Director Margrace Buckler said she hasn’t heard too much from employees concerned about changes yet. But she said a generous defined benefit plan is very important in the city’s recruitment efforts.

“You know our pay is lower than private, and pensions and benefits have always been the way to try and balance that out and try to attract people,” Buckler said. “There is something to be said for a defined benefit plan. You know what you’re going to get.”

The city task force is only evaluating the situation and developing options to deal with it, Yoakum said. Those options range from doing nothing to switching to a defined contribution plan — and Yoakum doesn’t believe either of those are viable solutions.

Yoakum praised McDavid’s foresight in tackling the issue early. Columbia is in a better position than many cities, Yoakum said, and it could have easily waited to act until the situation deteriorated further.

“I think the city has a challenge, but I don’t think it’s a crisis,” he said.