Under Their Wing

- "Under Their Wing" originally appeared in the October 2024 "Finance" issue of COMO Magazine.

The golden eagle Myria was a rare and magnificent sight in Missouri. According to the 1973 Missouri eagle census, he was one of only twenty-two golden eagles identified in the state. With his massive talons, towering three-foot height, and an impressive wingspan, Myria was a marvel of nature.

Tragically, Myria was shot in southeast Missouri, resulting in the near-total loss of his left biceps. The bullet rendered him flightless, jeopardizing his ability to hunt, fend for himself, and, ultimately, survive. But Myria’s story didn’t end there, however, thanks to the efforts of the Raptor Rehabilitation Project (RRP) at the University of Missouri’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

Project History

The RRP traces its history to the 1960s — more than fifty years ago — when many bird of prey populations were experiencing declines. In 1969, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service enlisted the help of Dr. William Halliwell, a pathologist at MU’s veterinary school, to conduct necropsies on eagle carcasses to determine the cause of these population drops. Their investigation, which led to the development of the RRP, revealed that the insecticide DDT was causing eggshell fragility and reproductive failure.

In 1973, after obtaining a rehabilitation license from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the RRP became the first licensed facility of its kind in the Midwest. The license allowed the facility to take in live injured birds, rehabilitate them, and eventually release the birds back into the wild.

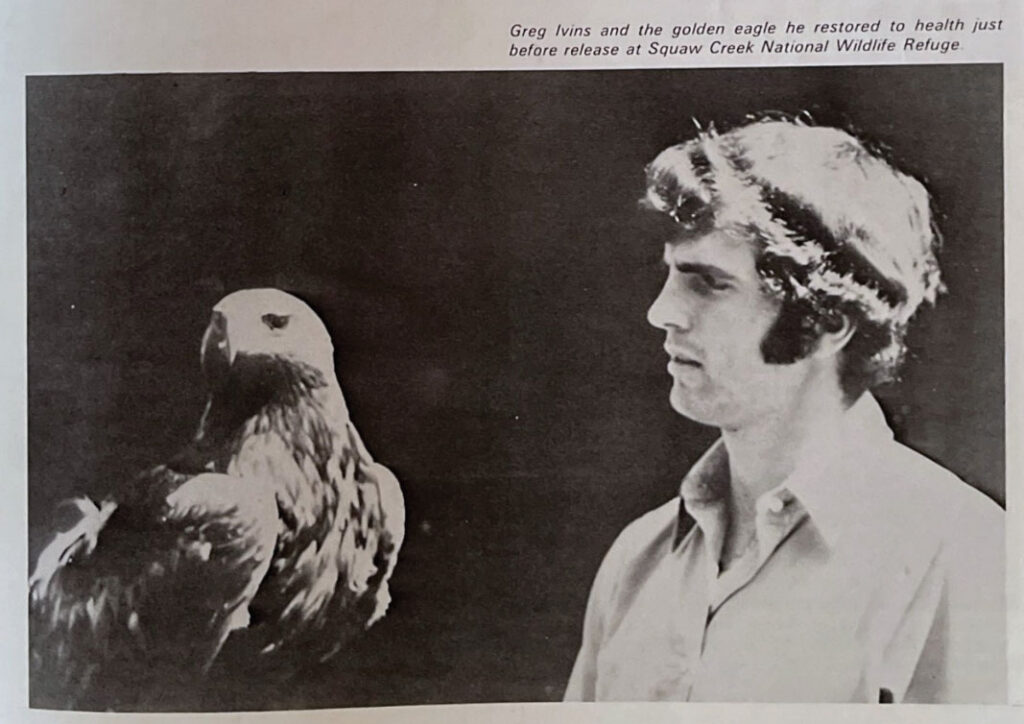

That same year, Myria entered the facility and became the project’s first success story, primarily due to the efforts of Dr. Halliwell and Dr. Greg Ivins, a 22-year-old graduate student (at the time) with a background in falconry. As the only veterinary student with such expertise, Ivins played a critical role in successfully returning Myria to the wild.

“Myria’s first flights were awkward and laborious,” wrote the late Joel Vance, an author and longtime writer with the Missouri Department of Conservation. “Though he used the undamaged breast muscles to move his wings up and down, it is the biceps that pulls the wing in and out and maintains maneuverability. Gradually, Ivins extended the distance of each flight until, after four months, Myria could fly a mile.”

At the four-month mark, the RRP released Myria. He was finally home once more.

Stepping Inside

The RRP lives in an unassuming building tucked away down a gravel drive beyond the College of Veterinary Medicine, bordered by lush greenery and mesh fencing.

Inside, the untamed spirit of nature meets the unwavering dedication of bird caregivers. The volunteers work to rehabilitate injured raptors, such as barred owls, red-tailed hawks, and turkey vultures, with the goal of releasing them back into their natural habitats.

The facility is supported by thirty-five community members, veterinary students, and long-time volunteer Lizette Somer, who now manages the project.

“We feed them [the birds] seven days a week, we fly them, we exercise them … and it takes quite a bit to train somebody [on bird care],” Somer explained, noting that it can take anywhere from four to ten hours just to train new volunteers on feeding routines. Much of bird care also involves detailed husbandry, like pulling weeds from the fence line and cleaning enclosures.

The timeline for a bird’s rehabilitation and release depends mainly on the type of injury sustained. For example, fractures may take seven or more weeks to heal, followed by mandatory flight tests to rebuild muscle strength and measure the bird’s likelihood of survival in the wild. Birds with head trauma are iffy cases, according to Somer; those with ocular (eye) damage may require an extended stay and will need to complete tests to ensure they can find perches and their prey before being released.

Those with more severe injuries may become permanent residents if they’re unable to survive on their own. If trainable, comfortable in social settings, and having a good quality of life, these birds become education ambassadors who help bring awareness to the project’s initiatives through public presentations. Some of the birds include the Great Horned Owl “Minnie Pearl” (since 2017), the Turkey Vulture “Grimm” (2015), and the American Kestrel “Hephaestus” (2003).

Aiding the Mission

The rehabilitation center is always seeking transporters and volunteers. Individuals must be at least 18 years old, attend meetings, and complete training (if working directly with the birds). For more information on volunteering, please visit their website.

Editor’s Note: If you find an injured raptor, call 573-823-9398.