COMO People: Same book, different page

MU English professor gains unexpected perspective with prison outreach

“What happens when the world ends and you have to start over? What do you look back on? What do you want to keep?” Those are the questions John Evelev asks.

He and his colleague, Bill Kerwin, are English professors at the University of Missouri.

Two years after the COVID pandemic first panicked the planet in 2020, John and his University of Missouri colleague, Bill Kerwin, were leading a class at the Moberly Correctional Center in reading Station Eleven, the smash-hit 2014 pandemic novel by Emily St. John Mandel.

John and Bill, English professors at MU, were building the foundation of MO-POP — the Missouri Prison Outreach Program — with MCC and MU. The program is small. Bill has taken on the program’s administration. He and John collaborate in teaching.

“Many of the students haven’t gone to college, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t value it or think it’s important. In fact, many students that we are working with in Moberly are actively getting degrees. So they’re very eager for enrichment generally,” John says. “It’s a kind of existential choice. Now that they’re in prison, they’re thinking about what they’ve done, but also what the future holds for them.”

For some of the students, the future holds degrees. This summer more than 700,000 incarcerated people are expected to gain Pell Grant eligibility. Legislation passed by Congress in 2020 will end the nearly 30 year moratorium on the federal, need-based grants for incarcerated people.

For many, though, access to formal degree programs will still be out of reach. For others, degrees might not be the goal. And for a few, the rest of their lives will play out inside the walls of a prison, yet they sign up for reading programs.

Art imitates life.

The students behind the walls at MCC did not stop seeking meaning or enrichment when their lives were uprooted by incarceration. In that, they are like the troupe of St. John Mandel’s characters, propagating art after the end of the world.

In the book, a flu decimates the world’s population. Twenty years later, the story picks up with the Traveling Symphony, a group of actors and musicians, as they travel a circuit of cities around the Great Lakes region. They perform the works of Shakespeare and provide much needed respite from the post-apocalyptic world.

The book is themed to Shakespeare, a fact that was not lost on John’s students.

“Some of them started talking about Shakespeare, and their reading of Shakespeare, and which is their favorite Shakespeare play. And I’m thinking, ‘This is so different from our expectations,’” John says. “I mean, they’re comparing Julius Caesar and Romeo and Juliet. They’ve obviously read them all. Even as someone who was going in [to prison] clearly intending to teach, I still went in with biases and expectations. I assumed that they would talk really generally, and be digressive, that they wouldn’t actually have engaged really deeply with the text.”

The book club format provided the inmate students an opportunity to connect in ways they hadn’t before.

“There were people who weren’t part of each other’s same social circles,” he says. “In responding to each other, they were going, ‘Yes. I totally get that.’”

The students also connected in their acceptance of responsibility for their actions.

“There’s part of the logic in the book in which an actor moves through life and he never really takes agency or responsibility for his actions,” John says. “He’s having an affair, and the woman he’s conducting an affair with says, ‘You know, I don’t think of myself as a bad person.’”

The opposite was true for the students in his MCC class.

“They were very quick to go, ‘Look I take responsibility for my actions, I can’t just blame the system or society,’” he says.

John says he and Bill found themselves more willing to look at the nuance in the students’ situations than the students were.

“When you talk to these different populations, you see how important a part of people’s lives education can be,” John says.

Rebooting learning behind the walls.

Though grants may be back in prison education, outside of prisons higher education is flailing. Nationally, enrollment has dropped, tuition has skyrocketed, funding cuts have become expected, and departments are continually consolidated. Federal loans which have long funded the system are under scrutiny after leaving millions with a new reality of “forever debt.”

Americans have been questioning the value of higher education for decades, and many are choosing vocational schools as alternatives. Learning practical skills, both inside of prison and outside of prisons, can provide a viable future. That’s why the majority of federal money spent on prison education goes to vocational programs.

“What we study, and what we do, and what gives our lives meaning aren’t all the same things,” John says. “The fact that people like the incarcerated, who would have every reason to want to find practical skills, are just as much drawn to things like discussing literature with each other, tells us something about what’s really important.”

He thinks there is a place for all kinds of education in prison, and that there need not be a struggle between postsecondary education and technical education.

“It’s not that one thing is more important than the other. It’s that all of these things are important. They’re all part of our lives and our educations,” he says.

John sees teaching in prisons as part of his own continuing education, a role he would not have easily found when he started teaching in 1997.

The loss of Pell Grants in prisons led to shuttering the vast majority of postsecondary prison education programs just years before he became an associate professor. Students in prison were left in a lurch, and generations of educators lost decades of opportunity to work with people in prisons. The loss was staggering.

The moratorium left the work of prison education to volunteers and a few institutions.

One institution that found its own way is Saint Louis University. In 2020 the SLU Prison Education Program asked John to lead a reading group at the prison in Bonne Terre.

“Prison education is something I’ve been interested in, so it was really fortuitous when they contacted me,” he says. “I think I had reached a certain point where I was interested in starting to do a little bit more outreach, more public service — not just teaching young people, though that is still very fulfilling.”

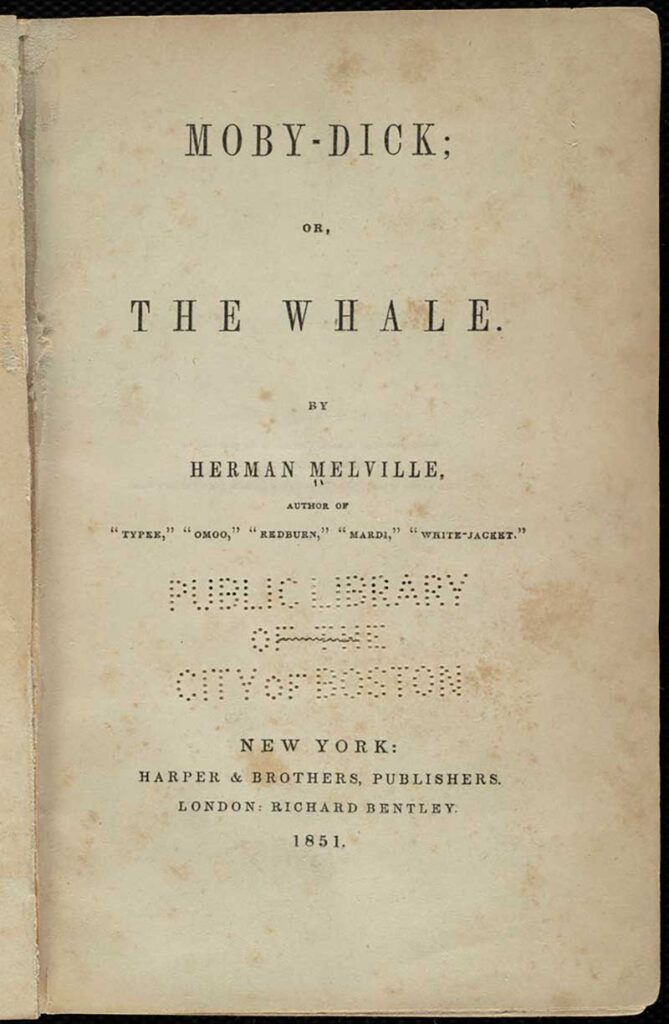

John’s specialty is 19th century American literature and cultural theory, and he has taught Herman Melville’s 1851 classic Moby-Dick to students on campus, in prisons, and at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, an MU extension for people 50 years and up.

His Bonne Terre students discussed a source text for Moby-Dick, Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea, a non-fiction book about sailors on a whaling ship that is attacked by a whale. In conjunction with the Philbrick text, his students read sections from Moby-Dick.

Moby-Dick is the monstrous white whale that terrorizes sailors in the Atlantic. The book follows Ahab, one such sailor previously maimed by the whale, as he monomaniacally seeks revenge.

John’s first discussion in Bonne Terre lasted two hours, the students covering most of the ground themselves: from what it means to ask readers to “Call me Ishmael” (a coy first line from a narrator, wary of using his real name), to Ahab’s fixation on the whale, to animal studies, to environmental issues. One of his students had read works by C.L.R. James, a Trinidadian author and activist who pioneered postcolonial thought. The student brought his knowledge to the discussion, opening a conversation about Black sailors in the Atlantic world. It was a whirlwind.

“I encouraged the students to bring in selections from Moby-Dick,” John says.

The exercise was meant to act as a gauge of the students’ reading. All of the sections they chose were all the ones John had considered important.

Paying close attention.

After his first prison class, John was exhausted, but was also exhilarated by the perspectives his students brought to the work.

“They were really close, careful readers. I tended to think you need to be taught how to look for what’s important [in a text], but I think if the subject is meaningful to you, it brings that sort of focus and intention. Now I don’t assume that all of these skills have to be taught,” he says.

Certain strategies are still important to impart.

For example, when reading Moby-Dick with his students at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, John discussed strategies for not becoming overwhelmed by the book. This group was reading the entire novel, unlike his class in Bonne Terre.

“Part of the project was going, ‘OK, don’t get stressed out about the book. We’ll work through it, and we’ll make sense of it. There are these long sections where nothing happens. That’s OK. We’ll understand what Melville is doing,’” he says.

John continues, “Every student brings their own life experiences and values to a class. It’s very different when it’s senior learners, in the case of Moby-Dick, because many of them had [unsuccessfully] tried to read it [before].”

They are not alone. Many people try to read the book without finishing it, and John wants them to know that that’s okay. He wants to validate readers’ experiences, to let them know that it’s okay not to like it, and it’s okay to not finish a book. Even this one.

“You should finish a book because it has value to you,” he says, “not because it’s the mark of your status or your intellectual capacity to finish Moby-Dick.”

Of the two, Station Eleven might seem like the lightweight, but they both jab at some of the same wasp nests. What happens when the world ends and you have to start over? What do you look back on? What do you want to keep?

In Station Eleven, the lead wagon of the Traveling Symphony’s three caravan has one extra line of text painted below their name. It’s a message that seems all the more compelling and poignant in the lingering haze of post-COVID living.

“Because survival is insufficient.”