Combined Efforts

Columbia nonprofits work together in supporting our community.

Many of the 142 Columbia-area nonprofits focus on poverty and social services. We can’t write about all of them, but we can highlight three important — and three very different — organizations.

In terms of budget and reach, the Mid-Missouri Assistance League, the Voluntary Action Center, and Central Missouri Community Action rank as small, medium, and large organizations respectively. Each plays a distinct role, and each makes significant impact on the lives of Mid-Missourians in need.

Though all three are well-established pillars of the community, their histories and the full scope of their work are not common public knowledge. But they should be. Knowing more about these organizations can help potential clients and donors, as well as the public at large, understand the missions and structures of these groups.

Assistance League of Columbia

You might not know the Assistance League, but everyone in Columbia knows Upscale Resale.

Just before 10:00 on a muggy Thursday morning in August, customers lined up to enter the pleasantly appointed resale shop in the Broadway Shopping Center, a few doors south of the Gerbes at Ash and Clinkscales.

Since Upscale Resale opened in 1999, its sales revenue has covered the larger part of the funds and goods with which the Assistance League helps area citizens, women, and children. The pandemic depressed revenues to some extent in 2020, as Upscale Resale had to close entirely for a couple of months and then had a period of limited hours. The store, though, has bounced back quickly. And it is not the league’s only source of revenue. Assistance League also participates in ComoGives, the umbrella fundraising and grants program. Individual and business donors, notably Shelter Insurance, also contribute.

In typical recent years, the league has disbursed $500,000 to $600,000 annually for the benefit of distressed fellow citizens. The assistance is indirect; the league supports other agencies that work directly with clients. In many cases, the assistance takes the form of physical goods — diapers, prom dresses, job interview clothing, school backpacks filled with school supplies, and so on. The Assistance League does not decide which clients get which aid; that’s up to the client-facing agencies, which, by IRS rules, must be nonprofit charities.

The school supplies effort is part of a national initiative, Operation School Bell, carried out by the 120 Assistance League chapters across the United States. The Columbia unit, founded in 1991 by Donna Beckett and Betty McClure, became an official chapter in 1994.

The local league also funds annual $2,000 scholarships for about 25 female students split between Columbia College and MU. The league does not take applications or select the scholars, instead donating to the schools, who then award the scholarships through their normal procedures, with a tilt toward military veterans and education and nursing majors.

The Assistance League currently has formal operation share arrangements with 10 other local nonprofits. One of them, True North of Columbia, a shelter and comprehensive aid program for victims of domestic and sexual violence, has been a league partner since 1998, when True North was known as The Shelter. True North remains one of the chapter’s top priorities.

The Columbia Assistance League chapter has about 330 volunteers who log well over 40,000 combined hours annually. During my Thursday-morning tour, dozens of volunteers could be seen working retail, receiving, sorting, cleaning, folding, labeling, tagging, assembling gift packages, and stored merchandise in the cavernous warehouse space in the back of the building.

The shop sells no new merchandise; all the clothing and household items are donated. Corcoran noted that the community has been generous to Upscale Resale in two Assistance League of Columbia ways: First by donating many quality items, and second by being loyal customers.

Some of those quality items end up with clients of cooperating agencies. The league works closely with Voluntary Action Center, which has many clients who are coming out of crisis and seeking a job or starting work after long periods of unemployment. Upscale Resale usually has a pretty good stock of office wear, so the league sends vouchers to VAC, and VAC sends clients to free Upscale Resale shopping sprees. The back-to-school kids’ clothing, all new, is purchased largely with proceeds from Upscale Resale sales. Again, the schools, not the league, select the students.

On that Thursday morning, the women worked within an atmosphere of cheerful camaraderie and beehive energy. They appeared to like both the work and one another.

Kathy Corcoran moved to Columbia from Washington, D.C., because her daughter had gone to college and then settled here. (Grandkids will make such a move happen.) She is a retired physicians’ office manager.

Phyllis Stoecklein moved to Columbia 20 years ago, after retiring as an elementary school principal in the Ferguson-Florissant School District in suburban St. Louis.

“I knew no one in Columbia,” Phyllis said. She came into Upscale Resale to donate some clothes, and a volunteer was made.

“One of the other volunteers said something a few years ago,” she said. “You know it’s the right thing to do when it’s below zero in December and you know that some little kid has gloves on his hands because of us.”

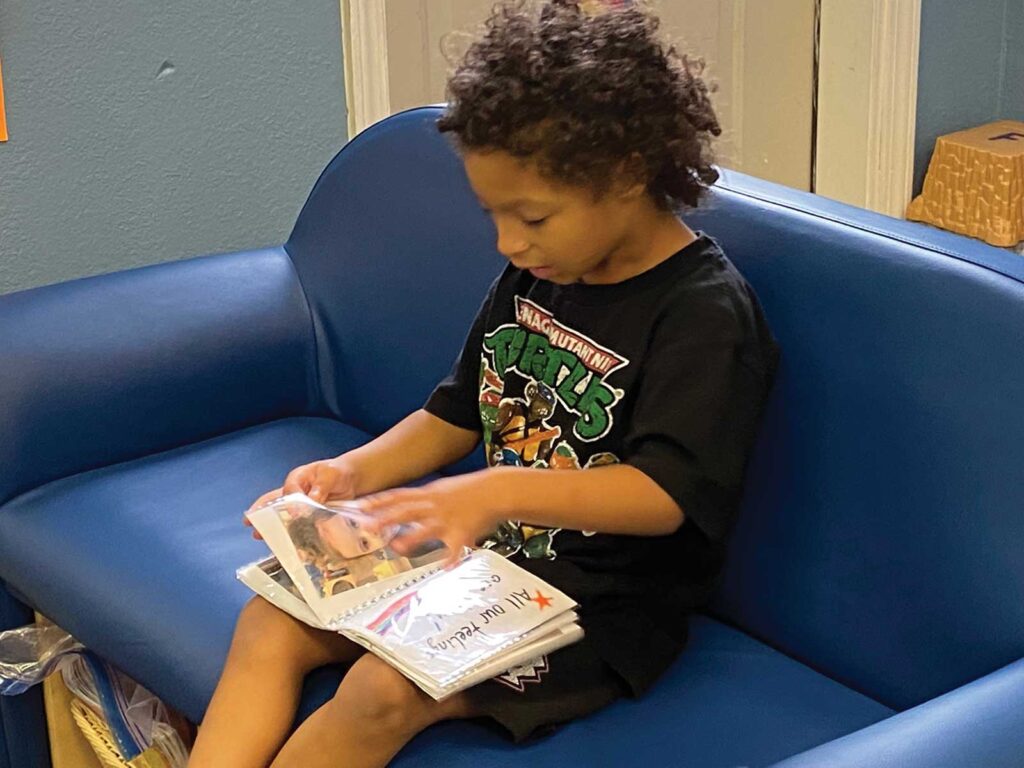

“Because of COVID, we had to sort and package the clothes for the school kids, and then the schools distributed the packages,” Kathy said. “But before that, the little kids would come in on the bus and we would help them. They had a shopping spree, and they were so cute and so grateful. These are the little things that keep you going.”

Upscale Resale and Chapter Offices

1729 W. Broadway, Ste. 1A

(573) 445-3848

assistanceleague.org/mid-missouri

Voluntary Action Center

The staff, board and donors of the Voluntary Action Center focus on the immediate needs of financially stressed citizens of Boone County. Many of those needs are physical and no less crucial for being mundane.

Heather Stewart, VAC’s director of development, told the story of a retired man with diabetes. He lacked the $7 to replace the dead battery in his glucose monitor. VAC found a way to solve the problem.

“That’s the sort of thing that defines us — crisis,” she says.

Heather has worked in several management, marketing, communications, and event planning positions in Columbia over the past 20 years. Just a few weeks after she joined VAC, COVID-19 sent her packing to work from home. She’s just now getting back to the office.

“The biggest pivot for all of us was learning to do a lot of the work by phone,” she says. “We had to get a new phone system. We had to learn to provide the same level of care and service in a completely different format.”

The silver lining: VAC staffers did learn to provide that service via phone, and that knowledge will stick when the pandemic ends. In the past, many clients were walk-ins and might sit in the lobby for hours to get assistance. Now, all meetings are by appointment via phone, and many services are settled remotely. That’s a plus for clients with limited transportation options for getting to the VAC office at 403A Vandiver Dr.

On the phone or in person, the mission stays the same: “To help low-income individuals and families bridge the gaps between crisis and stability and improve quality of life in Boone County.”

Crisis comes in many forms: dead batteries; re-entry after incarceration; homelessness; unemployment; dropping out of school for lack of funds; shut-off of power during winter cold or withering summer heat. To a parent, a hungry child is a crisis.

Housing, health, and employment have been the three top-level priorities for VAC since its founding in 1971. Those three things are, of course, closely related. For example: Many kids rely on school lunch programs for a significant part of their diet. When school lunch ends for the summer, VAC runs a Lunch in the Park program to make sure they get at least one square meal.

Summer also activates VAC’s air conditioner exchange program, formerly run by Columbia Water and Light. Low-income customers of Columbia and Boone County utilities can exchange old, failing, inefficient air conditioners for new ones. VAC also distributes fans, with Lowe’s as a partner.

For many years, VAC has brightened the winter holidays for its clients by collecting and distributing toys and other gift and food items. The emphasis is shifting, now, to cash donations and vouchers so clients can do their own shopping and make their own choices.

VAC has a staff of 18, including part-timers. The budget, which rose steadily in recent years ($507,000 in 2011, $774,000 in 2019), jumped to over $1 million in 2020. Priorities shift with the times. Housing took prominence in pandemic times, and VAC and its donors responded. In 2019, three donors contributed a total of $101,000 for housing. In 2020, 13 donors contributed $405,500. Heather notes that many donors signed over their federal stimulus checks to the organization.

That enabled VAC to hire additional housing specialists to get people sheltered quickly in emergency financial situations — that’s “rapid rehousing” in the trade. Housing assistance requires case management and eligibility screening. That takes expertise and staffing. (Hygiene pack distribution, as an example in contrast, requires none of that.)

“Also, it’s just really hard to find low-income housing that isn’t really crappy,” Heather says. She estimated that VAC assisted about 5,000 Missourians, many with emergency housing, in 2020. Some of that involved temporary placement in hotels and motels.

“We’ve seen COVID crises combining with ongoing financial crises for many people,” Heather says. “We’re serving about the same number of people, but those people have greater needs.” They are also seeing people who’ve been middle class their entire lives finding themselves in sudden crisis.

The City of Columbia, Boone County, and United Way of Central Missouri all fund VAC, but private donors anchor the group. In February, Heather signed on as VAC’s first staff development director, in order to boost private giving.

Voluntary Action Center has made a point of close cooperation with other social service nonprofits. That’s a good thing in itself, and it should help with fund-raising.

“Donors like to give to cooperative organizations,” she says. “They don’t like siloed entities. Many of the clients work with more than one nonprofit. They can’t get the wrap-around services they need unless we cooperate.”

VAC cooperates not only with the somewhat smaller Assistance League, but also with the vastly larger Central Missouri Community Action.

Heather says that VAC is built to cope with urgent, short-term needs, not long-term maintenance and life-building. VAC refers clients to CMCA for that. VAC and Assistance League work closely together on the immediate needs of clients.

“Assistance League has a diaper bank, and we have the infrastructure to get the diapers out to the parents,” she says. “So we don’t duplicate efforts. There’s a lot of sharing and referral among nonprofits in Columbia, much more than you see in most places.”

Voluntary Action Center

403A Vandiver Dr.

(573) 874-2273

vacmo.org

Central Missouri Community Action

Community Action dates to 1964, as part of the Economic Opportunity Act, the key piece of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. The act created VISTA, Head Start, Youth Corps, Upward Bound, collegiate work study, the Foster Grandparents program and, eventually, legal aid poverty law offices, among other efforts.

Johnson recruited Sargent Shriver to run the anti-poverty effort. Community Action, more than any other thrust of the War on Poverty, embodies Shriver’s belief that the poor must not only occupy a seat at the table, but also wield a bit of a budget and a measure of power to organize and plan independent action.

Many Great Society and War on Poverty initiatives withered as the Vietnam War consumed the nation’s resources and the Civil Rights Movement prompted reactionary responses to anything promoting racial or economic equality. During this era, poverty rights lawyers began suing local officials for discrimination in housing, employment, and education.

But Community Action has survived — and evolved.

More than 1,000 chapters, most funded through federal block grants to states, are active in the United States. Central Missouri Community Action is one of them.

In 1965, each Missouri county had its own Community Action agency. Over the years, leadership has consolidated. The City of St. Louis and St. Louis County still have their own chapters, but 17 other Community Action agencies cover multiple counties throughout the state. CMCA, based in Columbia, serves Boone, Cooper, Howard, Audrain, Cole, Callaway, Osage, and Moniteau as its core eight counties, and it provides some services to five more.

Head Start, the well-known preschool program for children from low-income families, is a big part of CMCA. Over $8 million in earmarked federal funding allows CMCA to bring Head Start to all 13 counties.

A “normal” — that is, non-pandemic — CMCA budget would be $17 million to $18 million. Emergency COVID-19 funding juiced that to $22 million in the 2020 fiscal year, which ended on September 30.

CMCA has an extensive mission, many initiatives, and a broad reach. It addresses emergency needs and devises and executes long-term plans for client families and entire communities. CMCA must think small and think big.

“The ultimate goal is moving people out of poverty,” says Darin Preis, CMCA executive director. “Stabilizing their situation is an important first step. But it’s not the last step.”

CMCA seeks to establish long-term relationships with client families and build on their strengths so they can, in Darin’s words, “walk out of poverty.”

A cohesive theory of change and a whole-family approach guide efforts throughout the organization. CMCA coaches are trained to guide families toward more extensive and productive social connections, including training in development of leadership and relationship skills as well as civic engagement and community involvement. CMCA supports improved family well-being through instruction in health, cognitive development, and parenting skills. The group also provides economic stability rooted in sustainable financial practices, career-level employment, safe and stable housing, enhanced education, and building of assets.

A family that enters the CMCA orbit through one program — Head Start, say — opens a door to many other programs, too. A coach could then direct that parent to a housing voucher program, or SkillUp employment training, or a USDA home loan program for rural residents. Entrepreneurial women can join the the Missouri Women’s Business Center, a CMCA program partly funded by the Small Business Administration. Help is out there, but most people aren’t aware of it, or have no idea of how to get to it. CMCA’s professional coaches guide them to the help they need.

Many people struggling with poverty feel isolated from and powerless within their communities. CMCA’s community organizing programs welcome citizens from all economic levels into their ranks. The prosperous learn to understand the stresses and needs of those in poverty. Low-income participants learn best practices for serving on boards, engaging in committee work and taking action to improve their communities. CMAC has placed professional community organizers in all eight core counties. The Community Action Teams — or CATS — that form around the organizers address a variety of community needs on a hyper-local level.

Government money always comes with strings attached, and these strings restrict how the money may be spent and how to account for it after it’s spent. Take federal weatherization funding, for example.

“We can use that money to bring a team to a home and do an energy audit,” Darin says. “We can find all the leaks and recommend ways to make the home more energy efficient. But if we find a giant hole in the roof, we can’t use the federal funding to fix it. We have to raise private money for that.”

Though CMCA receives substantial federal funding and a fair amount of state funding, it is not a government agency. It is a private nonprofit. As such, the group has increased its fundraising efforts to expand and enhance its services generally and to have more latitude in its actions.

Darin says that civic groups — Rotary, the Columbia Chamber of Commerce, and so on — have always given CMCA occasional donations. But private funding became more of a need for the group in the aftermath of a tornado in Jefferson City in May of 2019. Preis said that donors turned to CMCA because they knew it was stable and capable of helping.

“Now, banks are taking an interest,” he says, “as well they should. Families that come out of poverty establish bank accounts, buy houses, and take out mortgage loans.”

CMCA is also raising its profile and participating in more public-facing fundraisers, too. It is one of six nonprofit beneficiaries of this year’s Tigers on the Prowl gala auction, which took place on September 14.

CMCA commits to adopting, adapting, and applying data-based measures to analyze outcomes of its work.

Darin says that accountability for government dollars mostly has to do with “crossing Ts and dotting Is” and thorough accounting practices. Regulators want to know where the money went, but they never ask how many families were lifted out of poverty. They don’t evaluate outcomes.

Darin very much wants to evaluate outcomes, and not just anecdotally. Hence the adoption of the “self-sufficiency matrix.”

“This will be the beginning of a new way of showing the value of intervention and improving our techniques,” Darin says.

The matrix tool quantifies at five levels — from “thriving” down to “in crisis” — of economic self-sufficiency in housing, access to services, child care, clothing, education, employment stability, and 19 other dimensions.

That generates a lot of numbers, but the people CMCA serves are not numbers. When someone signs on to a program, they become CMCA members.“They’re not cases,” Darin says. “They’re human beings.”

Central Missouri Community Action

807 N. Providence Rd.

(573) 443-8706

cmca.us