Reflections of a Black Woman

As a lover of history, the opportunity to reflect on Columbia’s history intrigued me. As a Black woman and a resident of Columbia, the nuances of the subject matter — those that many find too intimidating or uncomfortable to discuss — compel me to talk about them in ways that are meaningful. As I reviewed articles, statutes, and case law, I was struck by the complexity of race relations in Missouri as a whole and in Columbia and Boone County specifically.

I am a Black southerner of slave descent and no stranger to the discussion of slavery. I grew up in the South and have seen cotton fields and plantations. This was part of our history and should thus be embraced — not because it was a great time for our nation morally, but because it is a testament to how far we have come and how much farther there is to go. But when I looked at the founding of Columbia, I was surprised at how difficult it was to find information on slavery in Boone County. The harder I had to look, the more I knew this would be the focus of my piece.

Slavery

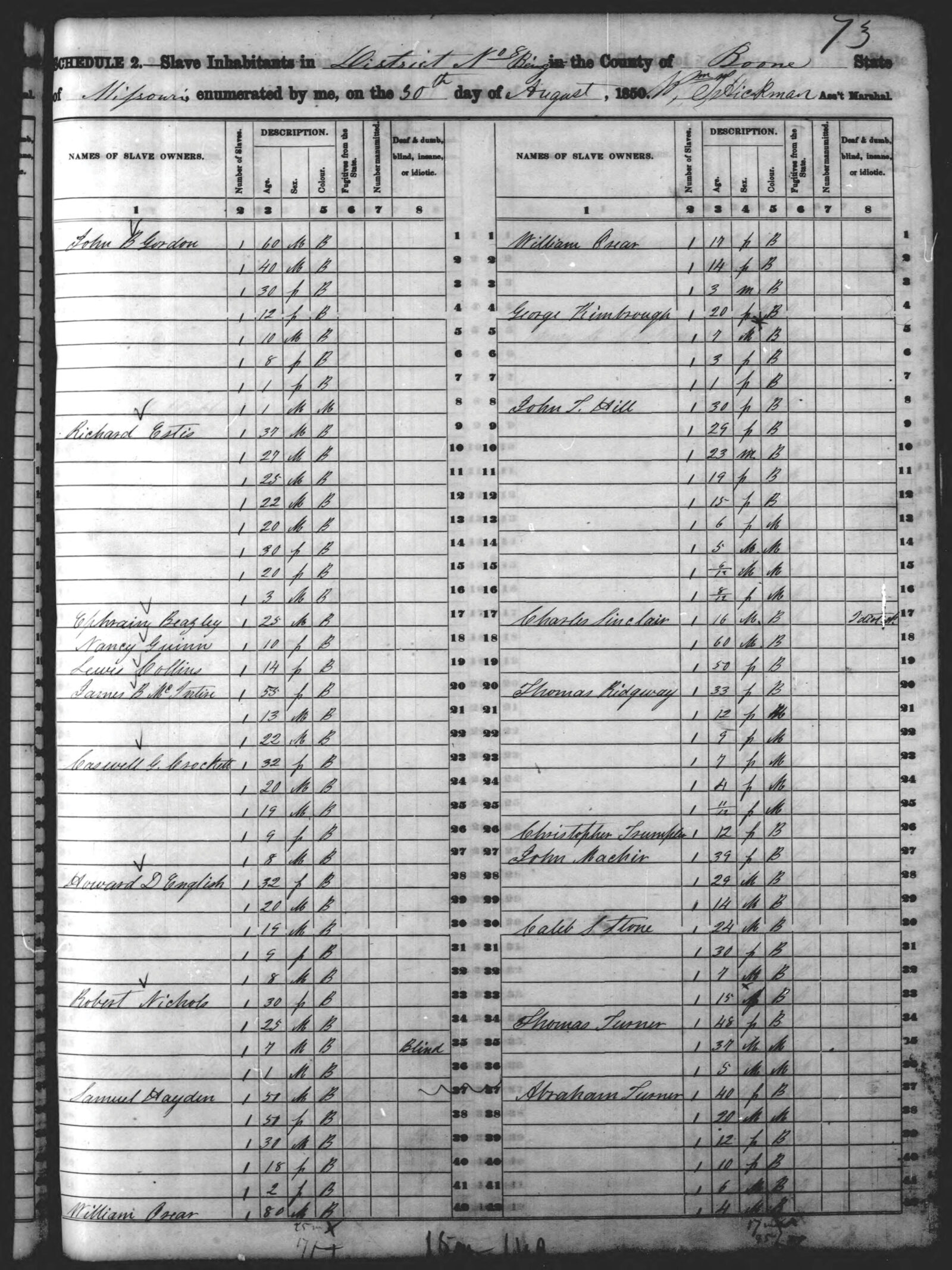

When I reviewed an 1860 slave schedule, I was struck by how sterile the records are. Having researched my own family history as a descendant of slaves, I know other records exist that allow slaves to be viewed as something more than just property. Even the simple inclusion of their name can humanize them. I realize that slaves were seen by slave owners as nothing more than property at the time, but reviewing the slave schedule helped me see just how little care was given to recognize a slave’s humanity. The only information obtained for identification was the name of the slaveholder and the slave’s race, gender, skin color (complexion), ability, fugitive status, if they were free, and the number of households. There were no names for slaves, just numbers.

Columbia was founded and built by the hands of slaves. According to the 1860 census, Boone County had a total population of 19,486 people. Of that, 14,399 were white, 53 were “free colored,” and 5,034 were slaves. Columbia had a population of 3,207. Of that, 1,756 were white, 12 were free colored, and 1,439 were slaves. I found it shocking that, in 1860, 45% of people in Columbia were slaves.

Missouri was progressive in that it abolished slavery on January 11, 1865, before the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime, was ratified in December of 1865. But the abolition of slavery did not end the struggle for equity or equality for Black people living in Columbia or Boone County.

Imagine living in Columbia in 1865. The Civil War has ended, the Thirteenth Amendment has passed, and the General Assembly has already enacted statutes mandating the establishment and maintenance of separate schools for white and colored children. Even though the Confederacy lost the Civil War and slavery had been abolished, there still was an entrenched belief that white and Black people needed to be separate. In the eyes of many, Black people were no longer slaves, but they were still inferior. And there was still a way to maintain power and dominance over Blacks.

I cannot imagine the rollercoaster of emotions Black people of this time must have felt. The joy and relief that they were free, and exuberance when they learned the Fourteenth Amendment (providing equal protection of the laws) and Fifteenth Amendment (that right to vote could not be denied because of race) were both ratified. Things were finally looking up. Sure, it may take some time, they must have thought, but it was going to get better. Little did they know they would soon deal with the helplessness, anger, and heartbreak of watching the U.S. Supreme Court dismantle the progress that had been made.

In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upheld racial segregation by ruling that the “separate but equal” doctrine did not violate constitutional rights. This decision would become the foundation of the Jim Crow laws that were quickly enacted throughout the U.S. It would be decades before the harmful effects of this era would begin to be undone.

Education

Many slaveholders feared the education of slaves and pushed to prohibit it. At the time, Columbia was already a center of higher education with Stephens College, the University of Missouri, and Columbia College all being founded in Columbia between 1833 and 1851. On February 16, 1847, the Missouri General Assembly passed a law prohibiting “Negroes or mulattoes” from being taught to read or write, attending worship services, and preaching unless police presence was available during the entire assembly. It also prevented free Negroes and mulattoes from immigrating to Missouri. The penalty for violations could result in a fine of $500 (valued at $16,283.78 today), imprisonment not to exceed six months, or both a fine and imprisonment.

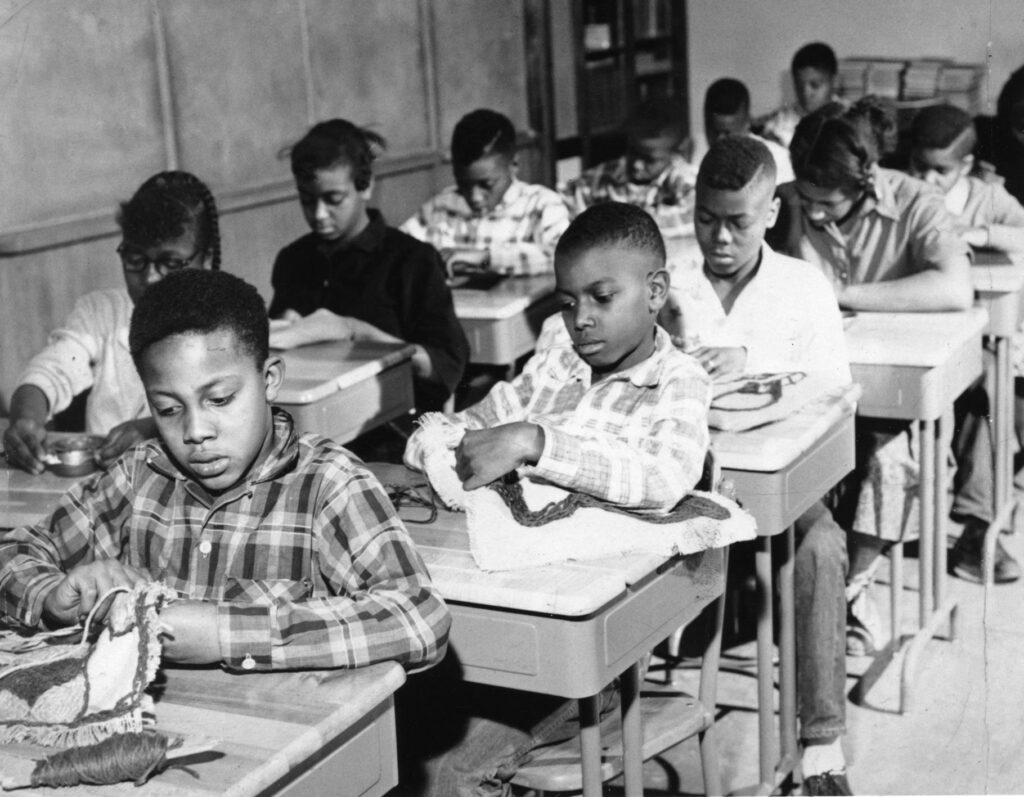

After the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, the first school for Black children was established in Columbia during the 1865-1866 school year by St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church. The Black Baptist Church completed construction of the Cummings Academy in 1866. The Cummings Academy received state and local funding and became a part of the Columbia school district once it was formed in 1872. The school district would go on to purchase a lot on the northeast corner of Park Avenue and Providence Road, which would become a future site of Cummings Academy. The name would change to Excelsior School and then to Frederick Douglass School. Under the leadership of H.A. Clark, Douglass School went on to establish a program with Lincoln University to ensure students wishing to attend the historically Black college met the entrance requirements. Clark also introduced industrial training to students.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court, via the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, put an end to segregation in schools by finding that the “separate but equal” doctrine violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Five days after the ruling by The Supreme Court, the Columbia School Board voted to end segregation.

When you look at our education system today, you can’t help but see that while schools have been integrated and there has been progress, the issue of equity has not been fully addressed. Some schools in the district receive more money than others. Middle schools and high schools do not receive Title I funds. Test scores highlight the achievement gap in education between white and Black students. While there has been progress, there are underlying issues that have not been adequately addressed to provide all students with the opportunity to succeed.

Higher Education

Segregation was a part of higher education in Columbia, too. MU was founded in 1839. Lincoln University was founded in 1866 in Jefferson City by men of the 62nd and 65th Colored Infantry.

Missouri statute provided for separate white and colored schools. In 1929, the General Assembly established Lincoln University as the school for the “Negro race.” Section 9622 of RSMo 1922 allowed the Lincoln University Board of Curators to “arrange for the attendance of Negro residents of the state of Missouri at the university of any adjacent state to take any course or to study any subject provided for at the state university of Missouri, and which are not taught at Lincoln University and to pay the reasonable tuition fees for such attendance; provided that whenever the board of curators deem it advisable they shall have power to open any necessary school or department.”

This brings us to a pivotal case with regard to higher education and the separate but equal doctrine. It started when Lloyd Gaines, a graduate of Lincoln University, was denied admission to MU Law School. In 1938, the Supreme Court decided under Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada, Registrar of the University of Missouri, et. al. that the University of Missouri had to either admit Gaines or build a law school on the campus of Lincoln University. The ruling paved the way for integration in higher education, but Gaines disappeared before he ever had the opportunity to attend the University of Missouri.

Eventually, the University of Missouri would admit a group of Black students in 1950. In my research, I was unable to identify when Black students were admitted to Columbia College or Stephens College.

In 2015, we came face to face with the reality that racism was still alive and well on the University of Missouri campus. A combination of protests, including a hunger strike by MU graduate student and activist Jonathan Butler and a strike by the Mizzou football team, along with a list of demands from Concerned Student 1950, resulted in national attention and ultimately the resignation of then UM System President Tim Wolfe and MU Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin.

Social Justice

Columbia has a unique history regarding social justice. One cannot reckon with it without first considering the lynching of James T. Scott in 1923. Accused of raping a 14-year-old white girl, Scott was arrested and taken into custody. He maintained his innocence, but before he was able to have a trial, a mob forcibly removed him from his cell and took him down to the Stewart bridge, placed a noose around his neck, and hung him.

In 1952, the Committee on Racial Equality began working in Columbia to advance racial equality. CORE would conduct sit-ins with racially mixed groups requesting service. Eventually, they would enter negotiations with the business owners in order to ensure Blacks were being serviced.

Final Thoughts

The events of last summer following the murder of George Floyd highlighted the deep-seated roots of racism, bias, and privilege in America. The Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum and brought to the forefront tough discussions about social justice, structural racism, systemic racism, and equity. These conversations were celebrated by many and criticized by others.

If it were understood in 1865 that providing Black people with access and opportunity would not diminish access and opportunity for white people, perhaps history would have been different. When there is a mindset focused on scarcity, one is forced to protect their own interest. Unfortunately, that protection often comes at the expense of another.

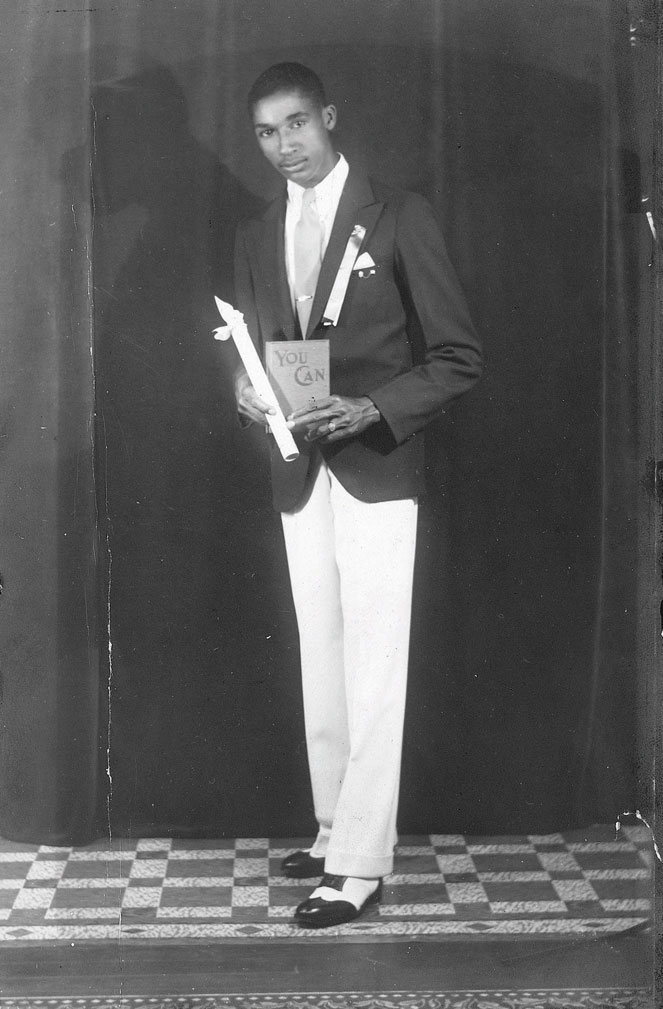

The history of Black people in Columbia is rich. Despite the oppression, violence, and hatred faced by our ancestors, they fought for a future that their descendants could be proud of. They recognized that nothing would be given to them, that they would have to work — and work hard — to succeed. They understood the power of community and became businessmen and women, entrepreneurs, musicians, caterers, doctors, lawyers, and dentists. They served in the military with distinction. They were farmers, teachers, and electricians. They were the hope they wanted their children to see.

The future is bright. A new generation is poised to tackle the challenges before us with empathy, compassion, and an eye toward equity. We are as committed to the future generations as our ancestors were to us. The story of our success is a testament of our resilience. The work required today to dismantle systems of oppression is just as daunting as the work of our ancestors. We all have a responsibility to learn from their stories and create meaningful change in education, health care, finance, and legal systems so everyone has access and opportunity to live a successful life. In many ways, things have changed for the better, but in many ways, it seems we are still fighting for the same things.