Positioning Columbia for a Prosperous Future

Since its inception, Columbia grew with mindfulness to the future about what kind of community its people wanted it to be. But Columbia’s history is not without times of struggle — times when strong leadership needed to step in and set or reset its course.

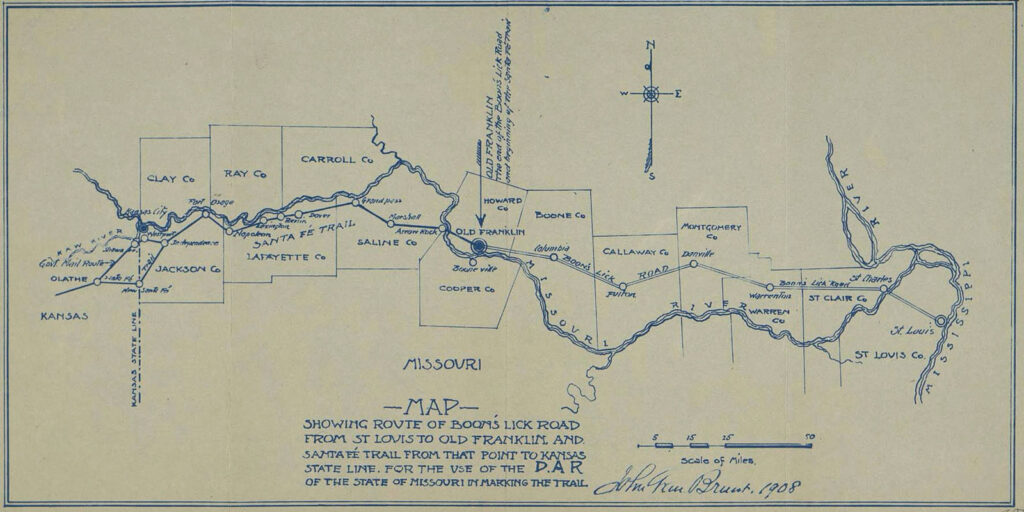

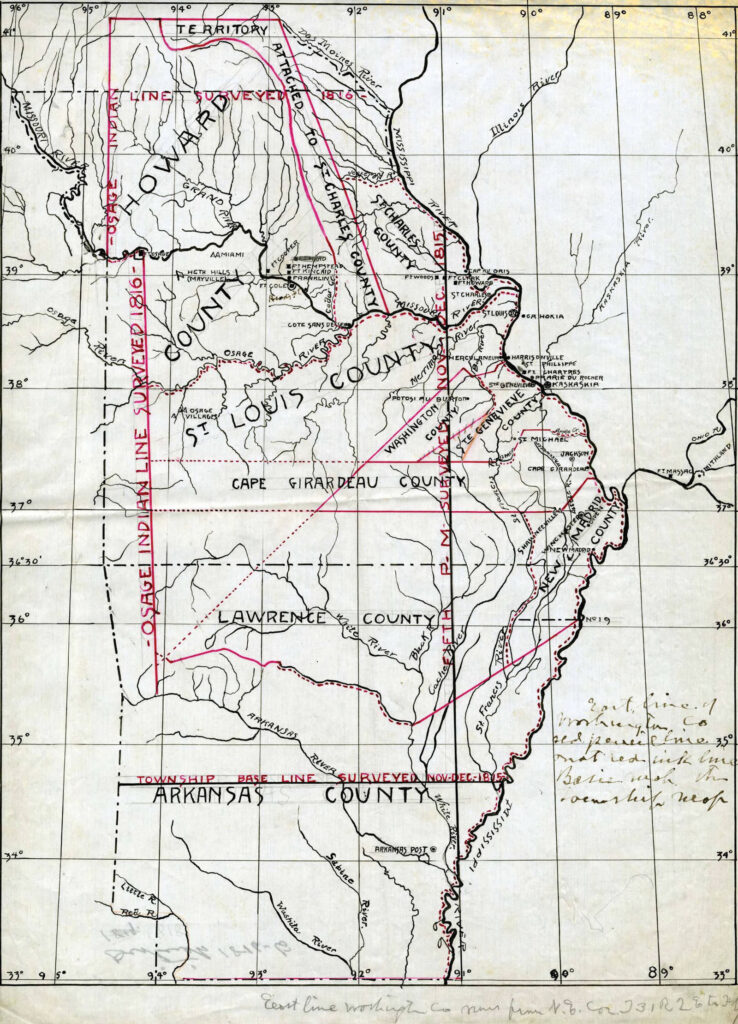

In 1818, Howard County extended from around St. Charles to the Kansas border. It was anticipated that this extensive county would be restructured to form multiple, smaller counties. A group of land speculators, the Smithton Company, decided to purchase land in the wilderness near Old St. Charles Road, also known as the Boon’s Lick Trail.

At the time, it may have appeared the speculators made a mistake. They did not buy land along the Missouri River, nor did they purchase land on the Boon’s Lick Trail; rather, the company’s land was about five miles south of the trail.

While details are unknown (although one could speculate that the confusion was due to crafty businessmen) a group of woodsman in 1820 created a “short cut” through the woods. Starting around what is now Williamsburg, the short cut went south and passed through the new settlement that would become Columbia.

The first settlement established by the Smithton Company, named Smithton, failed due to a lack of water supply. Moved about one-half mile eastward, the new site would be called Columbia and was adopted as the county seat of the newly formed Boone County on April 7, 1821.

Peter Wright, a surveyor by profession, had come to Boone County in 1817 from Tennessee. He established the town plan for Columbia, was appointed county surveyor, and designed the layout for Columbia in early spring of 1821.

Mr. Wright’s design provided for wider streets and alleys than normally seen during that time. While he could not possibly have known at the time, his plan allowed for easier transition to the automobile in the 20th century.

Once Columbia was secured as the county seat, the Smithton Company began to sell and make land donations that would fundamentally design Columbia’s future. One of their first priorities was to make the “short cut” in the Boon’s Lick Trail a permanent road. This was done, with Broadway becoming part of the new permanent trail.

The Smithton Company set aside land for a seat of justice. David Todd was the first judge of Boone County Circuit Court. His brother, Roger North Todd, was the circuit court clerk. They were the uncles of Mary Todd, later known as Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. The decision also helped make Columbia a political center. This would be important as Boone County sent representatives to the Capitol to shape the new state and ensure Columbia and Boone County’s interests were heard.

The Smithton Company also donated land for a public market. As the county became populated, the surrounding land was used for agricultural purposes. The market provided a trade center for Columbia. In addition, Columbia positioned itself, by moving the Boon’s Lick Trail, at the center of commerce flow, across Missouri. The Boon’s Lick Trail’s connection to the Santa Fe Trail allowed Columbia’s trade to expand to the south as well.

Columbia became a hub for businessmen and professionals, such as lawyers and doctors. Columbia attracted doctors not just because of local needs, but because it was a stop for travelers needing medical treatment to continue their journeys west.

Finally, the Smithton Company gave ten acres of land for an institution of learning. This would set the tone for the importance the community placed on education and would give rise to the institutions of higher learning that ultimately helped Columbia secure the state’s first land grant university.

While the first decade of Columbia’s existence was one of active establishment of business, judicial systems, trade, agriculture, and houses of worship, the next decade would build upon early plans made for education.

By the 1830s, there were common schools in Columbia’s district, which would become what we know today as public schools.

Columbia could also boast about its higher education opportunities. In 1833, the Columbia Female Academy was organized. After its closure in 1855, David Hickman helped secure the college’s charter under the name Columbia Female Baptist Academy — known today as Stephens College.

Columbia College for men, the predecessor of the University of Missouri, began operations in 1834. It helped further establish Columbia as a community invested in education.

Columbia was not the only city trying to secure the state’s first university. When the bids were opened in Jefferson City, Boone County came in first, Callaway second, and Howard third. Boone had successfully obtained the bid by providing $82,300 in cash and $36,000 in land. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1840.

In 1851, Christian College, which would later become Columbia College, was established.

Columbia would feel the impact of the Civil War. Through strong leadership, Columbia would remain in the Union, but the war was devastating. It would hit the educational system particularly hard. Columbia’s recovery was slow following the war.

The university’s fire of 1892 almost caused Columbia to lose the institution to another town. However, Columbians rallied to secure Columbia as the home of the university. This would be a time of rebuilding, both on campus and throughout the city. Columbia paved Broadway, began a sewer system, and established a paid fire department. Columbia’s investment in itself would find business improving and the community growing once again.

Mary Hale, a future Columbia architect, was born in Columbia in 1868. She would come of age during a time of struggle for the town, but she benefited from the foresight of those early settlers that valued education, including education for girls and women.

After graduating from the state university, Miss Hale would enter the male-dominated profession of architecture. Two of her most prominent Columbia designs were St. Clair Hall and the Calvary Episcopal Church. The story of St. Clair Hall is a tale of two intelligent, professional, female leaders coming together during a great time of rebuilding in Columbia to leave a lasting legacy.

Mrs. Luella St. Clair became president of Christian College, now Columbia College, in 1893 when the trustees named her successor to her husband after his death. She is credited with the modernization of the college. Part of that process was an extensive set of building projects to help move the college forward to answer the needs of its female students.

Mrs. St. Clair held true to her beliefs in the empowerment of women when she hired Miss Mary Louise Hale as architect. Miss Hale designed St. Clair Hall to house administrative offices, a library, three floors of dormitory rooms, and a dining area. Construction was completed by Christmas of 1899.

During the fundraising stage of the Christian College building project, tragedy struck the Episcopal Church in Columbia. On Easter Sunday, April 10, 1898, a fire damaged the church on Broadway.

The Rollins family offered to underwrite the building of a new church as a memorial to Captain James H. Rollins, son of James S. Rollins. At their request, the church was built at Ninth and Locust Streets, closer to the State University. The family chose Mary Hale as the architect. Completed in 1899, Miss Hale’s design incorporated many of the church’s original furnishings.

Calvary Episcopal Church (Historic Inventory of Columbia, Missouri, P0052. P0052-72751-23. The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection.)

(Charles Trefts Photographs, P0034. P0034-2855. The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection.)

University of Missouri University of Missouri Photograph Collection, P0088. 026150. The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection.)

Williams Hall Groundbreaking (Henrietta Park Krause Collection, Missouri, P0171. 013138. The State Historical Society of Missouri,

Photograph Collection.)

Columbia and its educational institutions would continue to thrive into the 1900s. As this happened, Mrs. Mary Lafon (Hale, having been married), would become known for her unique home designs. Mrs. Lafon designed three homes on Westmount Avenue known as the “Peanut Brittle Houses” due to the unusual materials used in construction.

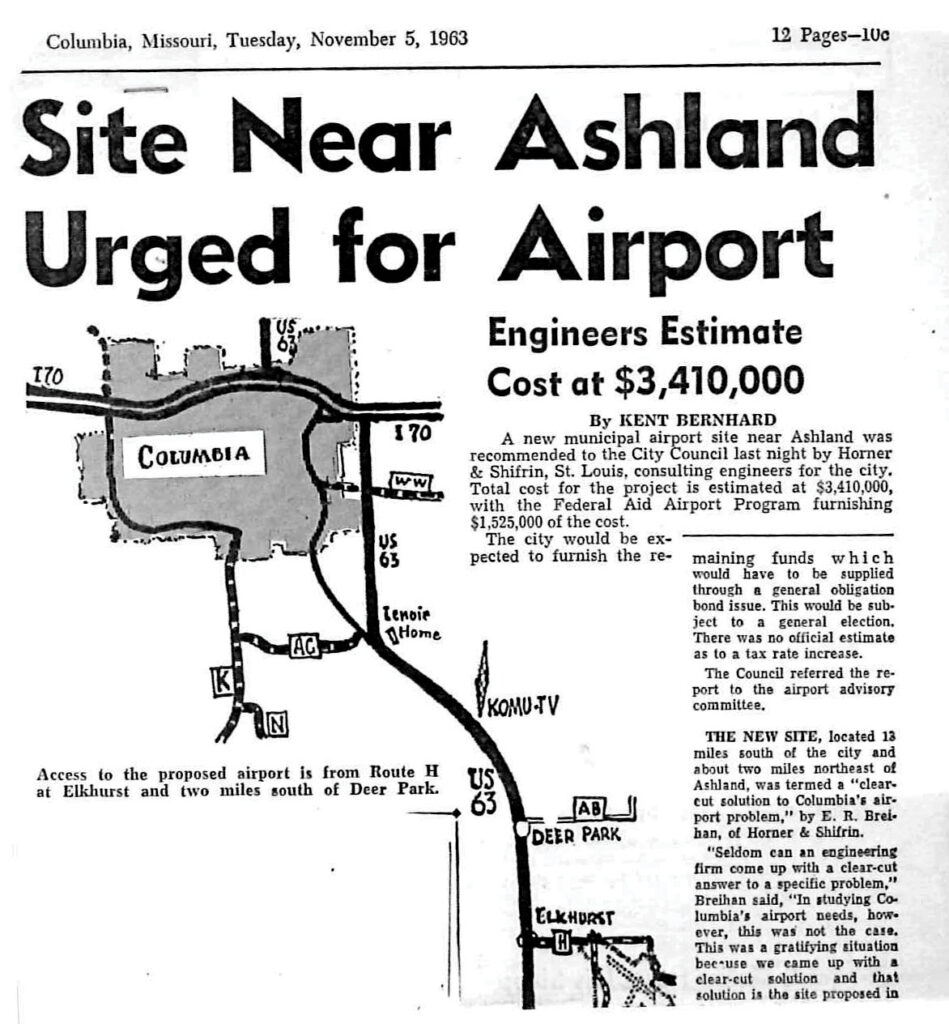

When the depression hit, Columbia and its educational institutions struggled. With the New Deal came the building of infrastructure, including highways. Columbia missed out on the railroad coming through town in the 1850s, so they lobbied with great enthusiasm to build I-70 along the old Boon’s Lick Trail to once again place Columbia at the center of commerce. Using similar logic, the regional airport was built amid the growth in air transportation.

Post-depression life brought a renewed focus on health care, as seen with the Ellis Fischel State Cancer Hospital opening in 1940. Columbia also adopted the city manager form of government, implemented infrastructure and housing projects, and underwent diversification of industry.

Strong and innovative leadership, paired with an involved and passionate community, has created the Columbia that we know today and will continue to provide for a prosperous future.