Mind the Gap: Educational Opportunities through CPS

Eighteen months ago, Columbia saw the possibility of two large companies building distribution centers or factories in the area: American Outdoor Brands and Aurora Organic Dairy. If the plans for these facilities were realized, hundreds of new, good-paying jobs would be available.

City, county, and business leaders debated the pros and cons of using tax incentives to sweeten and seal the deal enticing these companies to set up shop here. Columbia Public Schools superintendent Dr. Peter Stiepleman stepped into the policy discussions to support the tax incentive measures.

Stiepleman’s affirmative stance on the measures was unusual for a public school superintendent. After all, CPS receives roughly 80 cents out of every dollar of property tax revenue, so Columbia’s public schools would lose out on some potential money if the Boone County Commission granted the use of Chapter 100 bonds and tax abatement for Aurora Organic Dairy and American Outdoor Products.

Months earlier, CPS joined the Columbia Public Library and other taxing entities to weigh in on tax abatements for a major expansion of Dana Light Axle Products, which would create more than 100 new jobs. Stiepleman, who attended the meeting, said the best way to fight poverty was to create new jobs. Jobs meant more earning power for families and more stability in the community. Those benefits, he said, deserved his advocacy in the role of superintendent. After all, the school district was not immune to the ubiquitous challenges of poverty, socioeconomic inequity, and related ills that keep city, county, and public health policymakers busy exploring data and trying to stem the tide of poverty.

Measuring Opportunities for Enrichment

Students come from varying socioeconomic backgrounds, and CPS has to have some way of measuring which schools have the most students who need extra assistance. One of the ways this is done is through analyzing the district’s free and reduced-price lunch percentages. There’s a disparate range of rates among the district’s elementary schools.

Before speaking in favor of the tax incentives for Aurora Organic Dairy and American Outdoor Products, Stiepleman said he talked with former CPS superintendent Russ Thompson.

“When I spoke at the podium, I spoke from the perspective of a leader who had seen free and reduced-price lunch percentages grow from 25 percent in 2000 to 44 percent last year,” Stiepleman said in an email statement that reflected on his comments from the Dana abatements process.

There was very little Stiepleman could do in the short term to lower free and reduced-price lunch numbers. “Certainly, the long game is an excellent education that allows children to grow up to be productive citizens,” he says. “But what about now? What can we do now?”

In the case of American Outdoor Brands, the company planned to build a 1-million-square-foot facility just east of Battle High School and add 100-plus jobs that would pay at least $30,000.

“What an exciting possibility for our families,” Stiepleman says. “Because what we know is this: When families make more money, they invest it in their children.”

Bridging the Income and Educational Gaps

CPS Communications Director Michelle Baumstark said the trickle down of new jobs and more local economic activity — for instance, those employees shopping and spending locally — will help bridge income and educational gaps.

“It’s really a story of two Columbias,” Baumstark says, echoing the “tale of two cities” illustration that City Manager Mike Matthes has used to describe Columbia’s income and racial disparities. Baumstark said one part of the city is “well-educated, employed through the university, and well-paid.” In another part of the city, there’s “the service industry and lower wages. We’ve lost that middle sector. There aren’t a lot of well-paying jobs in that middle area.”

Dana Light Axle Products, Aurora Organic Dairy, and American Outdoor Brands all received Chapter 100 tax abatement incentives. Hundreds of new jobs that pay well will create new economic activity over the next few years.

Meanwhile, as Columbia’s public school district continues to grow and burst at the seams, education will become an even larger factor in the equity and opportunity equation. Putting new schools in or near the areas with greatest economic need is one way the school district can help shape the community’s demographics, but there are limits to that approach because lower income families experience a high level of housing instability.

Steve Hollis, human services manager for the Columbia/Boone County Department of Public Health and Human Services, is well-versed in poverty issues and social determinants of health, housing, and education. He has touted the Equality of Opportunity Project, based on a socioeconomic mobility study lead by Harvard researcher Raj Chetty, as a jumping-off point. Chetty’s study showed that children of parents in the bottom 20 percent of income earners were more likely than children in the top 20 percent to remain where they are along that distribution.

“Everybody, I think, understands that education is the key” to changing the poverty and economic mobility picture, Hollis says. He has advocated for requiring affordable housing around schools and for placing new schools in the most high-need areas of the community. Using free and reduced-price lunch counts as a proxy for poverty indicators and elementary schools as a proxy for place, Hollis has produced a draft report titled “Race and Place in Columbia and Boone County.”

The draft report mirrors the Chetty’s report’s keys to tackling poverty and inequity, quality public schools among them. Hollis says the local report seeks to “build a set of standing indicators” — a baseline for measuring future results of policy changes. “We’re early in the process,” Hollis says.

Hollis says CPS is especially progressive when it comes to taking on the achievement gap in which children from lower-income families without access to early childhood education often fall behind their peers when it comes to academic performance. Perhaps not surprisingly, there appear to be links between high free and reduced-price lunch rates and lower academic performance. Race correlates as well, as minorities are less likely to have early childhood education opportunities.

Hollis offers kudos to Stiepleman for shepherding tri-annual testing of students in order to “flag” those who are struggling. “I have to give Peter huge credit,” says Hollis. “He is doing an incredible job internally assessing this.”

Fighting Mobility Issues

Stiepleman points out a different kind of mobility issue that is unique to schools. Even within the district, lower income students and families often don’t stay put in one attendance area for extended lengths of time.

“We have schools with high mobility — where children move from one school to another during the school year — and we have schools with low mobility, where children, for the most part, remain all year,” Stiepleman said. For instance, Blue Ridge Elementary has a high mobility rate whereas John Ridgeway Elementary has a mobility rate of three percent, “meaning nobody leaves,” says Stiepleman.

When considering the city manager’s “tale of two cities” description, “mobility is the single greatest disruption to a child’s learning, and mobility is caused by insecurities such as housing, health care, child care, nutrition, and income, to name a few,” says Stiepleman.

Blue Ridge Elementary is an especially compelling example. Of the 90 children in fifth grade, only 19 have attended Blue Ridge Elementary since kindergarten. Among those 19, all but one student was proficient or advanced on the MAP test, which the state uses to measure academic progress.

“Ninety-five percent were proficient or advanced,” Stiepleman says. “That taught me that the system our school district has works, and consistency is essential for our students.”

Redistricting School Attendance Areas

Community demographics are among the factors that strongly influence the school district’s decisions when it comes to redistricting attendance areas for new buildings. That process is on the horizon again as the district plans to build a $34 million middle school in southwest Columbia in response to community growth and overcrowding at Gentry Middle School.

Gentry has a student load of around 900, but the building was designed for a capacity of up to 650 students. “You cannot send the entire population of south Columbia to that middle school,” Baumstark says.

An upcoming redraw of attendance area boundaries is on the horizon. Foreshadowing community angst to come, Baumstark said the new middle school boundaries will also affect high school attendance boundaries.

“No one is ever 100 percent happy when you do attendance area changes,” Baumstark says. “It’s a very emotional topic.”

Among the goals and priorities of the redistricting committee is “to make sure the attendance area is reflective of our community and . . . to try to balance demographics,” says Baumstark. With a school district that encompasses 300 square miles, that can be a tall order.

“You could gerrymander and create what a lot of people might consider the ideal demographic attendance area,” she added. But the process also avoids creating “additional disparities and lack of access by moving students from one side of town to another. . . . It’s a difficult process, and I think the committee really tries its best to take all those things into consideration.”

Public health officials are keenly familiar with the concept of the social determinants of health, which refer to housing, food insecurity, income, neighborhood environments, recreation and exercise opportunities, and other factors that can have positive or negative effects on health. Studies increasingly lend credence to the notion that a person’s zip code is as important as his or her genetic code.

“We can’t control where people live,” Stiepleman says in a 2016 video, “but we can make sure that all of our students are supported so that they can achieve at high levels academically, socially, and emotionally.”

Adopting a New Mindset

Under Stiepleman’s administration, CPS has adopted an approach they call “AEO” — achievement, enrichment, and opportunity. That has helped guide where the district allocates resources. For instance, the district has increased funding for early childhood education and instituted a two-day pre-kindergarten screening to help staff identify children who have the greatest academic needs. “It’s about equity and inclusion,” Stiepleman says. “That is an important piece of our work to keep them in class and catch them up.”

Some schools do have private, parent-led organizations such as a PTA, but those organizations are not operated or funded by the school. Stiepleman’s AEO plan is designed to advocate for equitable opportunities for all students.

“The district has worked hard to create equity and equality, which are achieved a number of ways outside of just parent fundraising,” Baumstark says. “It’s about making sure every student has what he or she needs to be successful.” For example, every third grader attends a performance of the Missouri Symphony, and all fourth graders visit the state capitol.

CPS also takes advantage of federal Title I funds, which are available for school buildings that show a need — based largely on free and reduced-price lunch rates — for additional resources, such as tutoring or specialized instruction in reading, language arts, and math.

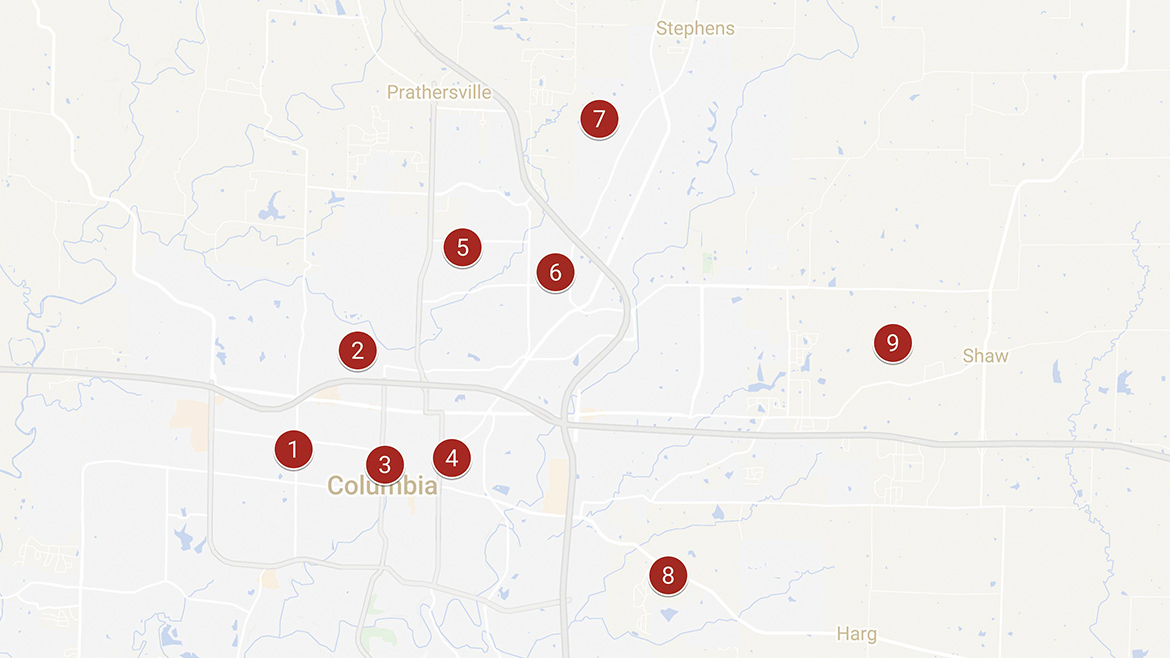

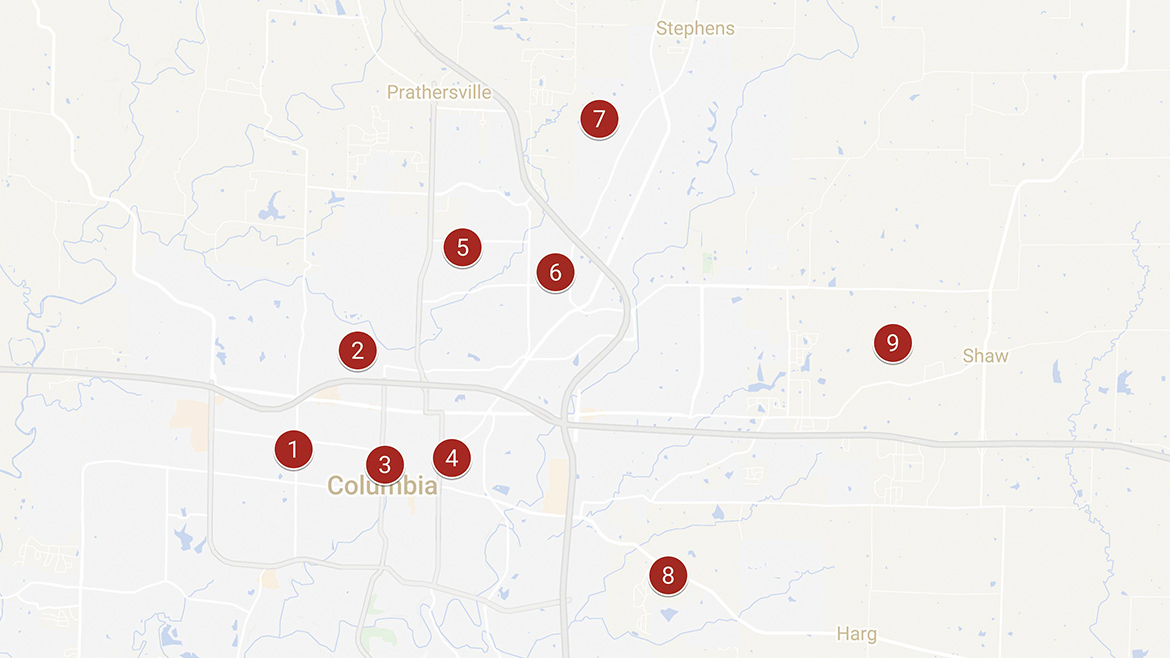

CPS follows a strict formula for Title I fund allocation. A school cannot be considered for the funds unless it has at least 35 percent of students on free or reduced-price lunch. CPS generally bumps that percentage threshold up to 50 percent. The district currently receives Title I funds for nine schools.

Baumstark said schools also receive support either in the form of volunteers, donations, or fundraising through a number of district programs including Partners in Education, Foster Grandparents, Junior Achievement, A Way with Words And Numbers, Assistance League, the CPS Foundation, and others.

“There are quite a few organizations that partner with us to help ensure all students are successful,” Baumstark says. “Columbia’s a great place to live. One of the reasons is we have a great school district. We have great community support.”