A Fresh Memory of Sharp End

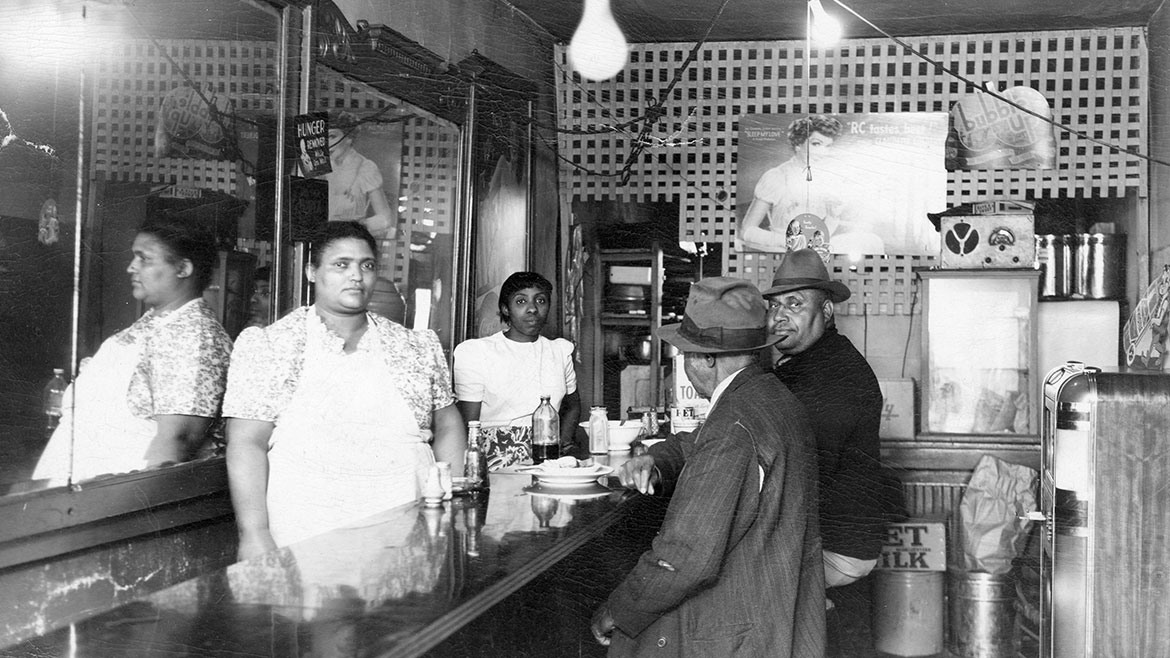

A view inside the Elite Café, located in the 500 block of Walnut Street. Edna Harris, left, and her husband, Robert, owned the restaurant during the late 1940s and into the 1950s.

With each new story, Jim Whitt uncovered a sense of the place he was learning to call home. The Columbia transplant, who moved here with his family in 2001, heard them on Sunday mornings at Second Missionary Baptist Church.

Whitt heard Deacon Larry Monroe talk often of a once-thriving black business district in Columbia known as Sharp End. It didn’t matter that more than 40 years had passed since the place had been marked on a map. Monroe was an affectionate and veracious storyteller who enlivened Whitt’s imagination with details of ordinary people and everyday activities.

But these weren’t merely nostalgic remembrances. Underneath this world, rich in personality and community, were deep wounds that cast a spotlight on the black community’s complicated relationship with the city that was their home.

A Placed People

One of the first black businessmen to leave his mark on Columbia was John Lange Sr., a 37-year-old free man whose family remained the property of MU president James Shannon. In 1851, with Shannon’s support, Lange opened a butcher shop at the corner of Fourth and Cherry streets. This operation, said to be the only meat market in the area for many years, prospered and allowed him to relocate and expand his business.

By the 1870s, Lange and fellow black entrepreneurs Gilbert Akers and Beverly Chapman owned most of the property north of Broadway between Providence Road and Fifth Street. The seeds of Sharp End would take root in this low-lying, swampy land near Flat Branch Creek.

Although the name has an uncertain origin, Sharp End’s value to the black community became clear as the new century brought increased segregation to Columbia. A restaurant, a pool hall, and a barbershop were some of the earliest businesses to emerge on Walnut Street, and the number and diversity of businesses only expanded with each passing decade.

Ed Tibbs’ father was one of the scrappy entrepreneurs who gave Sharp End its texture. Between 1930 and 1960, Tibbs’ father, who shared his name with his son, owned or operated a range of businesses, including Kingfish Smoke Shop and Shoe Shining, Central Marketing, Green Tree Tavern, T&T Smoke Shop, and Deluxe Billiards & Pool. He also booked many of the acts for McKinney Hall, a popular spot for budding black musicians like Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, and Billie Holiday.

“The Sharp End was the place to be,” Tibbs says. “You named it, they had it down there. But it was a place for adults. It wasn’t a place where kids or families would come and congregate.”

Sarah Belle Jackson moved to Columbia in 1938, when her father became the pastor at St. Luke Methodist Church, then located at 501 Walnut St. In an interview recorded in the book “Boone County Chronicles,” the longtime community activist, who died in 1999, describes Sharp End and its surroundings as the place “where you could really be yourself, where you had your own rules, nobody else ruled but you, the black people.”

One way that people expressed themselves was through their dress. Sharp End was known for being a place where people liked to look good while they danced or dined, shared interests or gossiped.

Although there was more to black life in Columbia than Sharp End, Whitt appreciates how it gave people an identity and helped them feel like their humanity wasn’t questioned.

“People believed in it, enjoyed it, and it provided jobs,” Whitt says. “It was a good thing for the community, because they owned it and made it theirs.”

A Reality Check

There was a time in Lorenzo Lawson’s childhood when his curious mind and love of learning had ample room to grow. At Douglass School, in an environment with caring and supportive teachers, he reached the top of his class. Then, in the fourth grade, schools in Columbia desegregated. He ended up at Ridgeway Elementary.

Suddenly, it felt as if a shadow chased away a bright spot in his life.

You would raise your hand to answer a question, but the teacher refused to call on you. You skipped school, but they didn’t care if you came or not.

“It made us become very rebellious, and, I hate to say it, we started taking it out on white classmates, beating them up,” Lawson says. “We were so angry about the way we were being treated, coming from an environment where you were nurtured, empowered, encouraged, inspired to get your education and go to college. And then, bam, nothing. They didn’t care if we came to school or not. It was horrible.”

Lawson looks back now and can see how his experiences and feelings correlate with many in the black community at that time.

On May 29, 1956, Columbia voters approved two commissions: the Columbia Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority and the Columbia Housing Authority. Those two commissions paved the way for urban renewal. The first plan, submitted for federal approval in 1958, focused on a 126-acre tract surrounding Douglass School. It included Sharp End. Many black-owned properties were sold or taken by eminent domain in the years that followed.

Some businesses from Sharp End relocated to Ash Street between Fourth and Fifth streets, but the new location, renamed “The Strip,” quickly faded away.

“Anybody at that time had a blatant reality check of what we ran into,” says Lawson, now 62 and the executive director of Youth Empowerment Zone, “because once those business started closing, we had to go to white restaurants, and we weren’t treated with dignity and respect.”

By 1966, remnants of Sharp End were gone. A parking lot ran the south side of Walnut between Fifth and Sixth streets, and the Columbia post office opened on the north side.

What was lost?

“Togetherness,” Tibbs says. “A lot of togetherness. And a little self respect, somewhere down in there, because it gave people a sense of being and accomplishment.”

Tibbs, 56, is one of the only black property owners downtown today. In 1986, he inherited a building his father purchased in 1943. Located at the southwest corner of Walnut and Fifth streets, it fell just outside of Sharp End. Today, it’s home to Tony’s Pizza.

Tibbs attributes his family’s business longevity to hard work, prayer, and the fact that “my dad was a hell of a man, and he had a hell of a son to come along with him.”

“Everything else down there is gone, and we’re still standing,” Tibbs says. “It hasn’t been easy. It’s been a lot easier for me than it was for him, I’m sure of that.”

A Lasting Remembrance

When Bill Thompson was a boy, in Fort Smith, Arkansas, a landscaping project awakened his fondness for history. It seemed like a fair arrangement to Thompson and his friends, a group of elementary-aged boys. They would pull vines from around the Old Fort Museum in exchange for an opportunity to see the collection of treasures in the brick structure.

The exploration struck something in Thompson, and since that time, he has made a point to dig into the background of the place where he lives. In Columbia, the discovery process is going on 40 years.

He is an enthusiastic storyteller and can easily narrate chapters of the city’s history as far back as the Civil War. In his office at Armory Sports and Recreation Center, Thompson pulls out a trash bag full of black and white photos the size of baseball cards. Some photos are in yellowing envelopes labeled “Seventh Street” or “Ash Street.” The rest are scattered randomly. Each photo has an address written on the back.

The photos were taken by Department of Housing and Urban Development photographers to show the conditions of homes and businesses surrounding Douglass School during Columbia’s urban renewal efforts in the 1950s.

Thompson was given the photos by the widow of Peter Hern, one of the original members of the Douglass Alumni Association, who found the bag in the trash. They sat in Hern’s closet for more than a decade before they were passed on to Thompson.

“I’ve learned to listen to people,” says Thompson, a recreation specialist for the parks and recreation department. “They know I appreciate and respect their history. It’s my way of trying to keep some of that heritage going.”

In 2014, Whitt formed the Sharp End Heritage Committee, bringing together many people with connections to Sharp End, including Thompson. He knew it would be hard for the city to move forward and cultivate minority businesses without first acknowledging the history of Sharp End and the long-standing frustrations and pains carried by those who felt taken advantage of when their economic and cultural heart was removed.

For a year, the committee worked in tandem with the City to create a historical marker for Sharp End. On May 19, 2015, in the shadow of the 10-level parking garage now standing at Fifth and Walnut streets, the marker was unveiled.

“We wanted to make Sharp End a real part of this community and ensure it didn’t disappear because it was never recognized,” Whitt says. “It’s a part of the history of Columbia, and we don’t want to lose that history.”

Georgia Porter, 83, was one of more than 200 people who attended the dedication ceremony.

“It was wonderful that they recognized it,” says Porter, whose father-in-law, James Porter, was a renowned pool shark in Sharp End. “But it was a sad feeling too, because it was gone.”

The committee is currently working to erect four or five more markers commemorating black history in Columbia. Whitt hopes the next marker, spotlighting the J.W. “Blind” Boone Home and Second Missionary Baptist Church, will be unveiled September 18. Each marker costs $2,000 and will be funded by private or public sponsors.

Once all the historic sites are selected, they will be linked as part of the city’s African American Heritage Trail. Columbia’s Parks and Recreation Department is helping with logistics, including installation, maintenance, and mapping. The proposal, submitted to city council in April, marked out a two-mile trail and about 30 spots of interest.

“We don’t have anything like it,” parks and recreation director Mike Griggs says. “This is going to be one of the more unique trails we have.”

Even though the geography may have changed and many of the buildings are gone, Toni Messina, the city’s civic relations manager, who has worked closely with the committee, is excited to see historical preservation reach beyond Sharp End’s boundaries.

“You don’t want to shortchange the story by making it be just about one thing — that’d be an incomplete understanding,” Messina says. “The ability to continue to mark and recognize sites, to me, is like uncovering more layers of our city’s story. It’s a worthwhile thing to do.”

A Look Forward

No one made a bigger impression on Lawson’s life than his grandmother, Goldie May Cross, who everyone called Miss Goldie. Not only did she manage a restaurant in Sharp End, she would also get up at 4 a.m. to wash and iron clothes for people, black and white.

As she became financially stable, she also became a local lending institution. People would borrow money and pay her back with favorable interest rates. She even worked out an arrangement with the owner of Dryer’s Shoe Store where she would send poor families to get shoes for their children before the start of school, with Miss Goldie picking up the tab.

“She loved her community, and she would help anybody whenever she could,” Lawson says. “When I look back, it had a huge impression on me because I have that spirit in me. When I see a need and there’s no one serving it, I begin to plan and strategize a way to meet that need.”

Lawson believes urban renewal not only destroyed small black businesses, it uprooted black doctors and dentists, and it “left a void for positive role models in the community.”

As each new marker is unveiled and the trail nears completion, Lawson and the Sharp End Committee hope to inspire another generation of young minority students to make their mark on the local community.

Whitt, 69, can already see this happening. Students from the Association of Black Graduate and Professional Students created a GoFundMe page in December 2015 to raise money for a historical marker remembering James T. Scott, who was lynched on Stewart Road Bridge in 1923. The marker will be unveiled September 30, near the intersection of Providence and Stewart roads. It will be a part of the African American Heritage trail.

“Going to school here, they feel like they’re part of this community,” Whitt says. “For them, to recognize what happened to James T. Scott is part of the way they were able to deal with all the turmoil happening on campus. It’s part of how they’re expressing themselves.”

Faramola Shonekan, 18, started her freshman year at MU in August. As a junior at Rock Bridge High School, she helped the Sharp End Committee record oral histories of Columbia residents. Those interviews, and the stories of perseverance and fortitude, trials and tribulations, made a big impression and solidified her decision to major in history.

“After each interview, I found myself stunned by the amount of things I didn’t know about black history and Columbia,” Shonekan says. “It made me realize that when looking at history, you can’t just look at the face of it. You have to look through it. There are more layers than what’s just at the top . . . I just don’t want this to be a quota for our community. I don’t want it to be a part of a checklist. I want us to go beyond that. I want us to be eager to learn from one another’s experiences.”

Lawson shares Shonekan’s vision. There is still a story to be told. The question is: What will that story be?

“Would it be possible to have something like a Sharp End again, where black businesses would be nurtured and given the necessary resources to thrive and create jobs, instilling that in children — that you can be a business person, that the sky is the limit?” Lawson says. “That’s my dream, that’s my hope, and that’s my prayer.”