After the Fire

Boone County is bracing for the economic fallout from a tumultuous year at MU — but how bad will it really be?

Just west of Jesse Hall’s front staircase, facing the Columns, is a skinny trapezoidal stone monument dedicated to the building’s namesake, former university president Richard Henry Jesse. It’s about 10 feet high and 5 feet wide at its base. It attracts good sunlight during the daytime. MU installed the monument in 1939 — a 100th birthday present to itself.

Jesse, previously a Latin professor at Tulane, became president in 1891, one year before Academic Hall (which was, at that point, essentially the entire university) burned down on a snowy night in December, famously leaving only the six columns salvageable. MU enrolled a little over 1,000 students at the time; around 5,000 people lived in Columbia. With the campus ruined, state officials considered moving the university to Sedalia, which had nearly three times Columbia’s population and was growing. Alarmed by the potential loss of one-fifth of their population and a significant fraction of their city’s jobs, Columbians raised $50,000 — about $1.3 million today — to rebuild the school in Boone County.

As president, Jesse led the campaign, and his work in rebuilding and expanding the school earned him the nickname “the Father of the Modern University.” His monument bears a quote, on its west face: “The University itself — its learning, its skill, its zeal, its enthusiasm — remains untouched, and its work will go on without interruption.” The attribution reads, “Richard Henry Jesse, 1892, After the Fire.”

At the end of the 2015-2016 school year, Boone County and MU found themselves in a better position than in 1892, but still not a very good one. Racially charged protests and the resulting backlash (and, seemingly, the backlash to the backlash) hastened an enrollment falloff that the school had been avoiding for years, even when comparable colleges began struggling to recruit new students. Throughout the spring semester, bad news came endlessly: investigations, threats to cut off state appropriations, meager application numbers, and on and on. At a forum in early March, Interim Chancellor Hank Foley, who assumed his job in November amid the protests, announced that the school would institute a hiring freeze and mandatory five percent budget cuts for all departments in response to an expected $34 million budget shortfall.

The partnership between MU and Columbia generally benefits both, which is why the city so steadfastly fought to keep the university in 1892; the college provides jobs for residents and human capital (put another way: skill, zeal, and enthusiasm) for employers, who get access to a constantly refreshing talent pool to grow their businesses. But with the university wounded, what’s at stake for the community?

To the Drawing Board

Throughout the spring, two MU officials— Vice Provost for Economic Development Steve Wyatt and Vice Chancellor of Operations Gary Ward — were reporting updated enrollment projections to the board of Regional Economic Development Inc., or REDI, on which Wyatt and Ward are ex officio members.

In recent years, under the direction of then-vice chancellor for research and graduate studies Hank Foley, MU turned to business development as means of creating revenue, which strengthened the school’s bonds with entities like REDI. Columbia’s broader entrepreneurship community refocused on collaboration as well, incorporating MU-adjacent groups like the Missouri Innovation Center with private and public enterprises like REDI and campus resources at MU and Columbia College. So, when Wyatt and Ward reported on enrollment to the REDI board, it was as a business partner in need of help.

“I think the business community has really rallied behind the university,” says REDI director Stacey Button. “And we’re working proactively to overcome anticipated shortfalls and potential drop-offs.”

I met Button and REDI’s vice president, Bernie Andrews, to ask how the business community might soften the impact of MU’s budget trouble. Both reiterated REDI’s staunch support of the school, but they also made a point to talk about other opportunities for growth: at the blue-collar level with manufacturers like 3M, for example, or at Columbia College, which has retooled its recruiting process and administrative structure to attract more four-year students and expand their programs.

“I think this community is resource-rich, and it’s a matter of coordinating effort between all of us,” Button says. “There is a very intentional effort to coordinate all of the resources together.”

Having a united support system in Columbia has counterbalanced the fury that some state legislators aimed at MU after the protests in November. Button recalled a trip she made to Jefferson City, accompanied by representatives from the city, county, chamber of commerce, and public school system, to meet with legislators. Originally, the trip’s three goals were to generate support for Columbia’s airport terminal project, transportation services, and projects at the MU Research Reactor. The fourth topic on the minds of state officials, Button says, was MU funding, and the informal diplomacy group found itself in the role of appropriations lobbyist.

“Again, I’ve seen this business community rally,” Button says. “No one is shying away from [MU]. We’re wanting to come together to ensure positive outcomes.”

Picking Data

In 2012, I came to MU from Denver as one of the out-of-state-tuition payers that bolstered the school’s finances in a time of sinking college enrollment (nationally, college attendance has declined every year since 2010, according to the Hechinger Report). The day after the hiring freeze was announced, in early March, when the threat of appropriation cuts still seemed very real, a professor of mine paused a class to say, “It’s much better to be a senior at Mizzou right now than a freshman.” In May, I graduated.

MU, by nature of being a public research university, was in a precarious situation before the protests even started. A study from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences reported states cut support to the median public research university by 26 percent between 2008 and 2012, evidence that appropriations fell steeply during the recession. Another study, from College Board, found that appropriations were 14 percent lower in the 2014-2015 school year than in the 2004-2005 year.

Colleges raised tuition to compensate, but MU was restrained by Senate Bill 389, which ties tuition to the consumer price index, thus limiting the school’s ability to raise prices. That bill, when passed in 2007, was coupled with a promise for more state support for higher education. State funding later fell off (by 26 percent between 2010 and 2015). The bill stayed in place.

In response, MU boosted out-of-state recruiting and opened up admissions, bringing in high-paying out-of-state students and increasing enrollment numbers, which peaked this past fall at a little over 35,000. But protests, and the enrollment drop that followed, again made state appropriations an immediate concern.

Since higher education funding began to fall nationwide, colleges have tried to argue their case through economic impact reports — research papers, almost always done by university researchers, about how reliable an investment in higher education can be. MU released one in 2005, early in the downward funding trend, and The Missouri 100, a system-appointed group of university advocates, commissioned another this past spring, pleading the school’s case to Jefferson City. The report emphasizes the UM System’s positive impact on lifetime earnings for Missourians (and the corresponding bump in income tax) and the role of university-based research and development in growing businesses. The report’s key findings include that Missouri’s economy grows roughly one-fourth faster thanks to the UM System’s R&D, that every one dollar reduced in appropriations to the UM system reduces the state’s real GDP by $38.48, and that an appropriations cut directed at the Columbia campus would be even worse. Likewise, every one dollar spent on appropriations would increase the state’s tax revenue by $1.46.

It’s easy to cast doubt on these types of economic impact reports, and many have. In a report for Duke University’s Urban Economics site, Michael Rebuck writes: “many of these economic impact studies exaggerate or incorrectly state the impact of their universities . . . A university’s goal of persuasion leads one to doubt the concrete accuracy of their reports.” Another report, from Vanderbilt University, was dedicated to troubleshooting the “methodological approaches and pitfalls common to studies of the economic impact of colleges and universities.” In that report, researchers point to inconsistency among economic impact reports as evidence of methodological flaws. In a survey of 138 impact reports, job impact multipliers (how many total jobs are created by one university job) ranged from 1.03 to 8.44. (In the Missouri 100 report, researchers did not use multipliers, focusing instead on other avenues of economic impact, like R&D.)

The impact that colleges have on their states — and, even more so, on their cities — is hard to quantify. For example, college towns generally rate extremely high in income inequality because students don’t generate much income, and some of them live, eat, and shop on campus, further complicating their relationship to their city’s economy. An unknown number of those students make essentially nothing but spend a lot, with financial help from parents or loans. And students also impact their city’s economy through the type of investments they attract, like student housing. These variables make it hard to establish a control group to study a university’s economic impact, so while there are undoubtedly positive economic effects present — like increasing human capital, raising lifetime earnings, and promoting growth through R&D — it’s hard to get a clear picture of how universities really impact their cities.

Which, of course, makes Columbia’s current problem harder.

Fighting through the Pain

Karen Miller was elected Southern District Boone County Commissioner in 1992. Her current term will be her last; in 2015, Miller announced that she wouldn’t be running for re-election. She’s spent part of her last year in office advocating for MU, locally and statewide (she was on the Jefferson City trip that Button mentioned).

Miller is also the vice president of the County Commissioners Association of Missouri; the group held their annual board dinner at Grand Cru, in Columbia. The UM System’s interim president, Mike Middleton, was there, along with MU Provost Garnett Stokes. Miller addressed the crowd.

“Of that board — and there were 20-some of us there — only one did not have a tie to the University of Missouri,” she remembers. “I had each one of them get up, introduce themselves, and tell if they had a tie to the University of Missouri, if they either graduated, they have kids who graduated, they have grandkids in school, their parents went there — they had a tie somehow to the University of Missouri. I tried to remind them that the impact was statewide. And when you think of the drivers of the University as a whole, and the income that they produce in this state for all of us, we can’t be badmouthing our number one impact.”

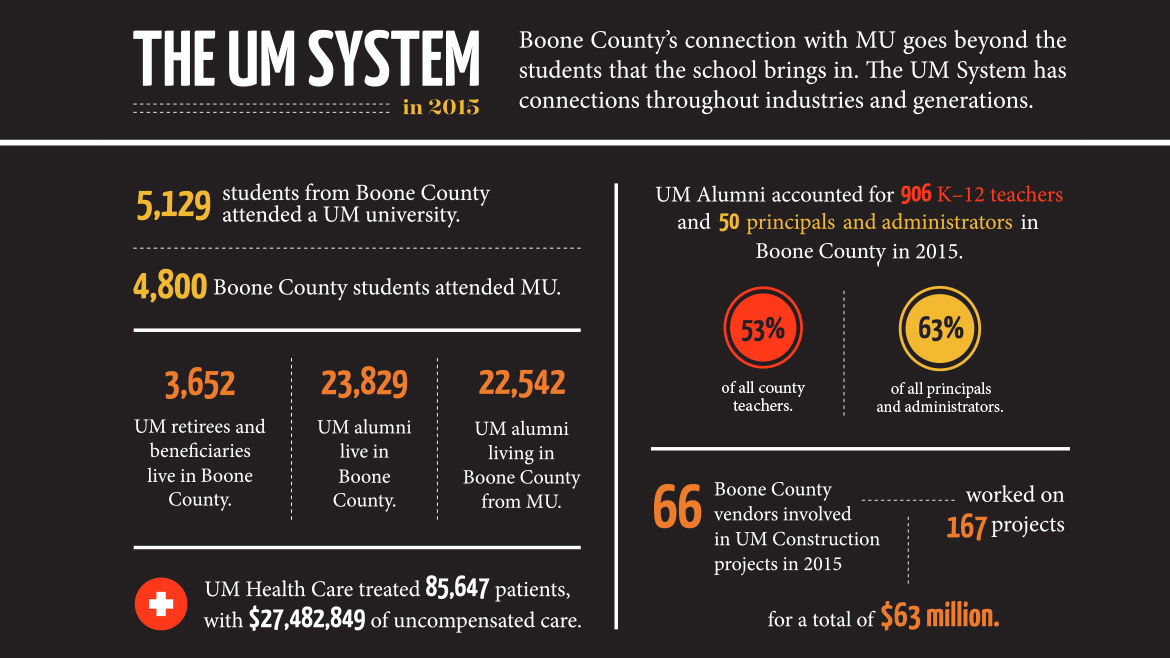

There are 18,193 UM employees living in Boone County, about 17 percent of the county’s total labor force. To Miller, the number speaks to the economic impact of MU, but also to the personal, emotional attachment that the community has to the school. To see national coverage of racially fraught protests at MU, then to see the fallout dragged over half a year, was shocking.

“I was out of state [during the protests], and every news channel, every paper, Wall Street Journal, USA Today — every time I turned around, we were on the front page,” Miller says. “It was embarrassing. And that’s what people were feeling. I think they were embarrassed because they honestly didn’t believe we were that backwards yet. I consider it backwards. I thought we were past that in-your-face — you know, there are bigots, and there are people who are prejudiced still, but I thought civility carried the day in our community. And I was very disappointed that there were things that were not very civil happening in our university.”

Miller says that, in the long term, the past year will be helpful for MU. The school’s diversity policy will be straightened out, and its finances will be trimmed to size and made more efficient. “I always look at lemons like, ‘Where’s the lemonade here? How can we turn this into a win?’” Miller says.

In the short term, the situation is painful. A five percent budget cut means position cuts and layoffs — at a REDI board meeting, shortly after Foley announced the budget shortfall, Ward said there might be 600 positions affected. At the time of this writing, in early July, after the new fiscal year has started for MU, there have been 38 staff layoffs.

The operations department, which Ward leads, was the first MU department to announce major cuts. Through various means, including assisted retirement, unfilled vacancies, voluntary layoffs, and involuntary layoffs, Ward eliminated 50 jobs. The cuts included a reduction in MU’s landscaping and trash removal services; the Columbia Daily Tribune’s article about the announcement led with, “The University of Missouri will be shaggier and dirtier and faculty will be responsible for taking their own trash to dumpsters under the plan. . .”

Ward was mildly ruffled by the media’s portrayal of the job cuts — he says there were only three involuntary layoffs — but he doesn’t dwell, nor does he apologize for acting quickly. “We’re operations. That’s what we do,” Ward says. “We have, I think, an obligation to our employees. We ask a lot of our employees, but we also treat our employees with respect, and one way we can do that is if I know something, I want them to know. It’s not necessarily that we have to shelter them from bad news — they just want to know the truth.”

Last fall, Ward was already expecting a budget tightening, though not as severe as the one that occurred, so the department was able to make some preparations before the mandatory five percent cut. But even then, some job loss was inevitable, and not just within MU. Suppose, given the wide range of possible job multipliers listed in university economic impact reports, that we conservatively say that every one job lost at MU means 1.5 jobs lost in Boone County. That would mean the 38 layoffs MU made by July will translate to 57 lost jobs in the community.

Budget cuts also have far reaching effects for MU’s (and, therefore, Columbia’s) business development efforts. Reducing expenses for the Office of Economic Development likely means easing back efforts at business growth. “That money is not going to be there,” Wyatt tells me. He sets up a hypothetical math problem: if you have $100,000, and somebody takes $5,000 away, then you just lost the ability to do whatever you were going to do with your $5,000.

Also lost are the indirect impacts of that $5,000, whatever money that $5,000 business development investment might have made for the community. The budget cuts leave some programs hamstrung — groups like the Small Business and Technology Development Centers, for example, will now have a harder time securing matching dollars from the university for potential grants. All resources must be directed to simply maintaining operations.

“The University Extension exists to explore and make things better, not just maintain the status quo,” says Steve Devlin, extension program director and leader of the SBTDC. Devlin is continuing to push his programs to grow in any way possible, but it’ll be harder now, for a lot of reasons. Devlin says, “Hiring freezes don’t work well when you have people retiring and people leaving for other opportunities.”

Brand Damage

“The time for bashing this institution, on our part locally, is over,” David Shorr says. I met him on a late afternoon at Lutz’s BBQ — his suggestion. Shorr is a REDI board member, a position he earned through longtime involvement in the public arena: he was director of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and he’s served in a variety of roles, both private and public, since then, currently as an attorney with Lathrop & Gage and a member of various boards. (Though not affiliated with this magazine, Shorr co-hosts the “Columbia Business Times Sunday Morning Roundtable” on KFRU.)

“The brand has been hurt,” he says. “I would love to see the data on shirt sales and things like that, which we don’t hear anything about from the athletic department. . . . In southeast Missouri, I bet they’re down. And I bet Memphis t-shirt sales are way up.”

Shorr, and others, say that the brand damage that resulted from the protests and following events accelerated MU’s enrollment problem, which is perhaps why officials like Button and Miller are eager to voice support for the university. The quicker MU can repair its image, the quicker they’ll be able to normalize finances. As Ward puts it, the school must “learn to ring our own bell.”

MU is the biggest business in town, even bigger when combined with MU Health Care. And even while celebrating growth in other areas, the community seems to recognize the prime importance of the university.

As part of Columbia College’s strategic realignment, the school has been adding programs and increasing four-year, on-campus enrollment, all while continuing to maintain a strong online presence and develop their athletic program as a recruiting tool. Kevin Palmer, vice president of enrollment and marketing, has overseen much of that effort, which came about via a larger effort to make the college’s administration more business-like. Even that has been affected by MU, which Palmer cited as an example of potential systemic problems in higher education.

“The challenges that they have at Mizzou are challenges that we’re seeing throughout our culture,” Palmer says. “We address them, and we look at them, as any serious person would, and that’s that there’s always room to improve.

“We love MU,” he added. “They’re the flagship university in our state. And we love having another cat in town.”

Shorr admits that he, at times, has offered less-than-constructive criticism of the university over the last year, but since Foley’s budget forum, he’s recognized the need for a united front. Now, MU has to buckle down.

Left Standing

The economic link between MU and Boone County is very real, even if that link is difficult to quantify and harder to predict. It’s been a painful year for the school and for its community. It’s hard to say exactly how painful the coming years will be. Wyatt compares this year’s enrollment drop to watching a python swallow a pig: once it’s swallowed, you watch it move all the way through, without getting any smaller. That’s to say, the problem won’t be solved in a year, and it probably won’t be solved in four.

Miller, now preparing to exit office, where she’s served as an advocate for MU and the community since 1992, is thinking long-term. “Opportunity comes out of crises in people’s lives,” she says.

Foley, who didn’t respond to interview requests for this story, seems to be thinking long-term as well. In his letter to the university, announcing the budget shortfall, he wrote, “While these budget challenges will affect our ability to deliver teaching, research and service to Missourians in the short term, we also know that we have survived other stressors of this kind before.”

Boone County’s relationship with MU has always been long-term; that was a promise made after the fire.