Mike Matthes: So, Why a City Manager?

Almost three score and ten years ago (no kidding), Columbia voters discarded the political party system and adopted a council-manager form of government. In 1949, we were categorized as a city of the third class — meaning 3,000 to 30,000 citizens, much smaller than today — but experiencing post-World War II growing pains, as the G.I. Bill made it possible for so many Americans to get a college education. From 1940 to 1950, our population increased 75 percent, from 18,400 to almost 32,000 people.

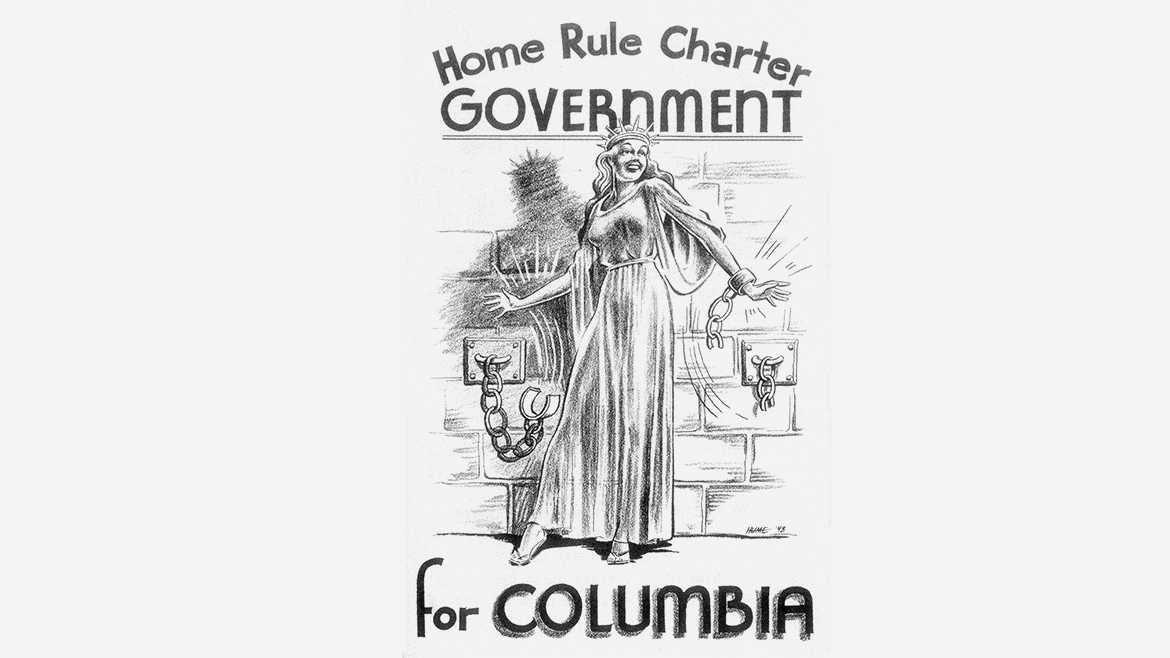

67 years later, there’s cause to celebrate the foresight of our ancestors. Their legacy, the council-manager form of government, is the foundation for the solid reputation and quality of life the city of Columbia and its citizens enjoy today. But why did they do it?

Those promoting “home rule” told voters: “If this proposed charter is adopted, control of the government of the city will be vested in its people rather than in the State Legislature. No longer will it be necessary to depend upon the General Assembly in Jefferson City for legislation to provide changes or improvements in our administrative organization … Any citizen will then be able to look into the charter to find the answer to his questions about the government of his city, instead of trying to find his way through a great maze of state statutes applicable to city government as at present.”

True enough, but there’s more to the story. In 1925, the home rulers tried but failed to get support for a charter. In 1948, they tried again, pointing out that the city property tax rate had increased from $0.63 per $100 assessed value in 1930 to $1.25 per $100 in 1948 (today it is $0.41 per $100 assessed value). That created more revenue, but not enough to support our water and light operating and debt expenses. The prospect of never-ending rate and tax increases without accountability to taxpayers raised alarms, as it should have.

There also were concerns about “petty” political influences from too many elected officials, including lack of citizen voice and gross spending inefficiencies. Home rule promoters advocated for a council-manager form of government. Under that model, elected representatives set policy, hired a city manager to carry it out, and retained authority to release the city manager.

After a lively campaign, 55 percent of voters approved the home rule charter, with 4,319 ballots counted in favor of the proposition and 3,557 ballots counted against it. Although voters have amended the charter over the years, it still stands as one of our founding city documents. The Columbia Charter Commission conducted at least part of their business on the second floor of the Metropolitan Building, the structure now home to Rally House, on the south side of Broadway near its intersection with Eighth Street.

I would love to know how Bill N. Taylor, Columbia’s first city manager, appointed in 1949, worked with the city council and employees to transition to the new form of government. Certainly, he could have consulted other communities for advice.

Staunton, Virginia was the first city to adopt the council-manager form of government, in 1908, and Excelsior Springs and Kansas City both adopted it in the 1920s.

Today, close to half of all U.S. cities with a population of 2,500 or more have a council-manager form of government. In these cities and in Columbia, a non-partisan, elected mayor and city council members share power and authority over policy making. No one has veto power.

Like a corporate board of directors, the council hires a CEO — the city manager — who reports directly to them, implements Council policy, has administrative responsibility for all programs and city employees, and serves at their pleasure. It’s basic good government.

With our city’s strong bond rating, balanced budgets, conservative fiscal policies and a collaborative city council attuned to engaged citizens, I’m always surprised when I hear talk of changing to a mayor-council form of government.

And IBM’s 2011 study of the nation’s 100 largest cities revealed a “performance dividend” at work in well-managed communities. Places with city manager forms of government are nearly ten percent more efficient than cities with strong mayors. Those results signify that quality strategic and operation decisions matter more to a city’s success than do external factors like population, geographic size and economies of scale.

According to the study’s results, “The lack of exogenous factors driving efficiency levels is a curious result … What the analysis does suggest, however, is that if those factors do impact efficiency, their impact is being masked by a much more important factor. And that factor appears to be management.”

Columbia’s performance dividend includes our current property tax rate (stable for years) of $0.41 per $100 assessed valuation. That’s two-thirds lower than the 1948 tax rate that drove people to the polls. Columbia’s share of your total sales tax is only two percent of every purchase, and half of that was approved by voters for parks, transportation and capital improvements.

With our city’s strong bond rating, balanced budgets, conservative fiscal policies and a collaborative city council attuned to engaged citizens, I’m always surprised when I hear talk of changing to a mayor-council form of government. I honor those Columbians who, 67 years ago, specifically dedicated their proposed charter “to the future citizens of Columbia.” We’ve got a good thing that serves us well.

I invite you to learn more about how our city’s charter came to be by visiting our website at GoColumbiaMo.com and searching “Charter.”

I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Toni Messina and Steven Sapp in writing this column.