The Business of Research

A college professor’s enthusiasm can come from odd places, like the thrill of strengthening collagen cells by affixing them with gold nanoparticles in a bioengineering lab and then publishing a research paper about it.

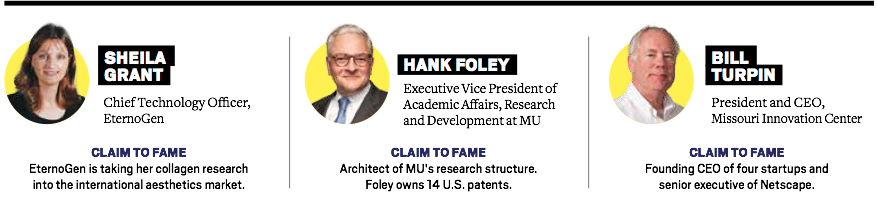

Before she became an entrepreneur, Sheila Grant had simple motivations. “I didn’t have any aspirations to own a company,” she says. “I was just a professor doing my job: researching, teaching and graduating students.”

She still does those things, as a graduate professor in the University of Missouri bioengineering department, but now she’s more enterprising. Grant is the chief technology officer for EternoGen, an international company that’s taking her collagen research into the aesthetics market in Europe and Asia.

A confluence of forces — new leadership, new resources and hotter coals underfoot — is bridging the gap between academic research and high-yield entrepreneurship at MU. The university wants professors to take their research from the lab to the consumer, and the perceived value of their intellectual property is shifting. To counteract a slowdown in funding, MU isn’t settling for small licensing revenue from its research: The university wants to create companies, and it wants them to be big.

The MU research office, led by Hank Foley, is doing everything it can to lead professors into business: investing money, setting up an accelerator, developing innovative talent, etc. When it comes to making business out of research, MU wants to be “best in the Midwest.”

Birth of a saleswoman

“When I was a Girl Scout, I didn’t even sell Girl Scout cookies,” Grant says. “I’m not a salesperson.”

EternoGen resulted from collaboration within the university. As Grant and her students were tinkering with collagen particles, the MU Biodesign and Innovation Program was looking for needs in the medical field that university research could fill. One such need was for a durable, injectable tissue for orthopedic use; Grant’s mega-collagen was the answer. Grant was still toying with the idea of commercialization when she got another push: An MBA student who worked with the research for a class project asked Grant to form a business. The student, Luis Jimenez, is now EternoGen president and chief operating officer.

Their biggest fan and biggest initial investor was MU. With the school’s backing, the team gathered investments and went international. They added a Swedish CEO, Anna Tenstam, whom Grant describes as “the Steve Jobs of the aesthetics industry.” EternoGen is putting orthopedics on hold for a while; Grant is optimistic that they can launch in Europe before 2016.

“The university has been very supportive,” she says. “I think that our new leadership has made it a lot simpler to start a company. The university really wants this to work because if we succeed, then obviously they succeed.”

EternoGen, in going from a research project to a market-ready product, has matured into an example of the private-public partnerships the MU research office wants to cultivate — and make money from.

When streams run dry

Hank Foley arrived from Penn State in 2013, the same year as Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin, and he has since happily immersed himself in the transformation of MU’s research development. His job requires that he find revenue streams in professorial research activity; the problem, in Foley’s estimation, is that the traditional streams have dried up.

“What we’ve tried to do is be more intelligent about intellectual property,” Foley says. “Telling outsiders, ‘This research belongs to us’ is a pretty unfriendly approach in this day and age.”

MU needs a friendly approach. When state funding for the university began falling in 2010, leadership began exploring ways to cash in on their most stable commodity: intelligence. That’s where Foley came in.

For more than three decades, most colleges have used intellectual property the same way. In 1980, after passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, universities using federal grants began retaining the licenses to their inventions and research. Those schools then began using that intellectual property to generate some steady licensing revenue. Foley estimates that MU brings in $8 to $10 million a year with this system.

That revenue is the lowest ranking of MU’s “enterprise” operations in its budget. An update from the 2014 budget, provided by the school, said the office of research, patents and royalty accounted for 0.2 percent of enterprise money.

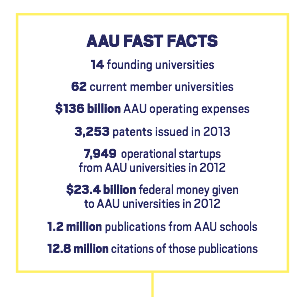

But MU has more than money at stake in its research department. The past five years have put the school in tighter financial  straits, but they’ve also rang alarm bells about MU’s membership in the Association of American Universities, the crème de le crème of research universities in the country.

straits, but they’ve also rang alarm bells about MU’s membership in the Association of American Universities, the crème de le crème of research universities in the country.

In 2011, the University of Nebraska, which joined the AAU alongside MU in 1909, became the first school to be kicked out of the club. Shortly afterward, Syracuse University voluntarily withdrew, suspecting it was the next one out.

The AAU judges members on eight criteria. Two are related to research grant funding; three are related to faculty qualifications, including published material, which influences grant money. The AAU doesn’t release rankings of member schools, but after Nebraska’s departure, MU administration — former Chancellor Brady Deaton, UM System President Tim Wolfe, Loftin and Foley — told the public that MU ranked 32nd out of the 34 public universities in the AAU. They made it clear that the school had to generate more interest from the federal agencies that fund research.

“As the margins in education get tighter, AAU membership is only going to get more important,” Foley says. “Entrepreneurial activity is good for Missouri, so it’s good for the university. But the things we want to do are making an impression in Washington, D.C.”

The licensing-first system is out. The new system, and part of Foley’s master five-point plan to find more money in research, is entrepreneurship. Foley wants professors to start companies.

Changing the world and floating boats

That plan assumes that professors and other university personnel also want to start companies. After all, creating a startup is difficult, especially when it’s counterweighted with a full-time professorship.

“A lot of universities didn’t know how to start companies, and they overvalued what they had,” Foley says. “They didn’t realize how much follow-up money was needed to get a product to the marketplace.”

At MU, that starts with collaboration. Case in point: EternoGen. Foley also mentions Newsy, the multimedia journalism company partially founded with university money in 2008. Five years later, E.W. Scripps bought the company for $35 million, a good chunk of which came back to MU.

Foley wants to see more of this: Even if MU doesn’t sell a company for three years, that’s still a sustainable pace if it sells companies for $35 million and up. “This is a real revenue stream that’s just not there right now, and we could be 10 to 15 times larger than we are,” he says.

The school’s new philosophy on intellectual property pivots on a culture of innovation. Professors will be encouraged to learn from other professors, even from other schools, who have taken research into the market and been successful. MU wants to educate faculty on their options. They want to build an empire of successful enterprises from the ground up.

The school’s new philosophy on intellectual property pivots on a culture of innovation. Professors will be encouraged to learn from other professors, even from other schools, who have taken research into the market and been successful. MU wants to educate faculty on their options. They want to build an empire of successful enterprises from the ground up.

“We want to take something that could be licensed and turn it into a company,” Foley says. “And that’s what big companies have told us they want. We would like to see Columbia, Missouri, become a hotbed for entrepreneurship.”

Another applicable part of Foley’s five-part plan is No. 2: create a class of entrepreneurs. MU wants to be a regional leader — “the best in the Midwest,” as Foley has said — but that will have to be a grassroots effort, starting with the students the school is producing.

“We’re not going to import people from Silicon Valley,” Foley says. “Well, except for one person, and that’s Bill Turpin.”

Bill Turpin was, in fact, imported from Silicon Valley, but he was also bred in Missouri. He was born in Bowling Green and grew up in St. Charles. He graduated from MU with a degree in electrical engineering. After a stint at Texas Instruments, he founded a string of technology startups, one of which was acquired by Netscape, where he began working in 1995. There, according to his Bloomberg executive profile, “his team developed some of the core technologies in the commercialization of the Internet.”

“I’ve mostly been in tech,” Turpin says. “And now I’m here.”

“Here” is the Missouri Innovation Center, of which he is the CEO and president. Turpin wields the demeanor of unblinking coolness that Silicon Valley folklore invokes; the focused clarity of his speech suggests innovation is a matter of routine for him.

The Life Sciences Incubator, which the MIC operates, is at full capacity under his leadership. They’re expanding the building’s wet lab space to allow more bio companies, many sparked by university research, to take up residency. Until then, they’re growing their tech portfolio. EternoGen is a client.

“It used to be that the university could create the basic resource and then buy a few patents, and industry would come in and do the rest.” Turpin says. “But in the last 10 to 15 years, the industry has changed. And the industry doesn’t want to do all that hard work anymore. They want the university to get a product ready for market.”

The MIC and the Life Science Incubator are scaffolding to university-born companies. Their mission is to get professors across the “valley of death,” as Turpin describes it: the strange, unknown wasteland between a brilliant discovery in the lab and application.

Despite the novelty of the entrepreneurial idea at MU, Turpin says the school is playing catch-up to the pack leaders. The week before his interview for this article, Turpin was at MIT, where they founded 900 startups in a year.

But Turpin agrees with Foley: MU can be the best in the Midwest, and there’s a tremendous financial incentive to do so. At MIT, Turpin was getting a team certified by the MIT mentoring program, with the goal of coming back to Columbia and breeding startups here.

“I’m just hoping that I can provide a little mentorship here or good advice there and help an idea that can change the world,” Turpin says. It’s a powerful theme for him, and he returns to it later: “Sometimes that’s all it takes. A fundamental desire to change the world.”

There are two hurdles to clear in MU’s aspirations of becoming Silicon Valley University: money and people. Both Foley and Turpin think money will come, even if it’s not all currently there. The school will, if everything goes according to plan, be rolling out a capital-raising accelerator before 2016. Turpin is lobbying for more teamwork and cooperation among different business entities in Columbia, including city government.

People are the higher hurdle. Who will lead the startups? Who will teach the people who lead the startups? Where will they work? Who will provide the research that spawns the product? Grant points out that a professor’s entrepreneurial success isn’t brought up at a performance review. There, more traditional metrics are examined: papers published, grants accepted, students graduated, etc.

“We want to encourage people to do this,” Foley says. “That requires not punishing them when they fail but dusting them off. I have an optimistic view that this can work and can raise all boats.”

Raising all boats and changing the world: the new ethos for intellectual property at MU.