Frozen

When she was interviewed for this article, Susie Adams was teaching a summer school driver education class at Battle High. The students, about 20 of them, had just come back from lunch, and it had been raining since before sunrise.

“Somebody made a joke to me this morning,” Adams says. “They said it would be easier to get a boating license today than your driver’s license. It was actually my superintendent that said it, so I laughed a little harder. You know you always have to laugh at your boss’s jokes.”

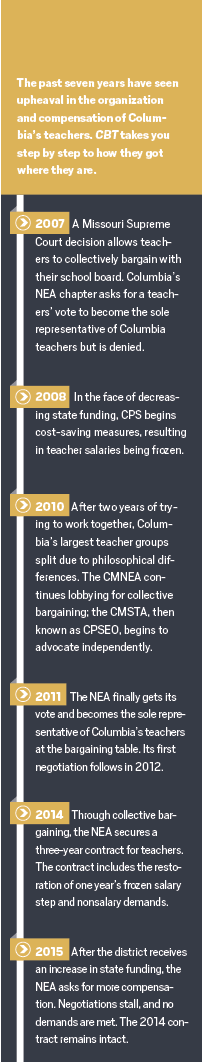

The relationship between CPS teachers and their district over the past seven years has been, at times, less friendly than such an off-the-cuff wisecrack from superintendent to teacher would have you believe. Teachers have been fighting to unfreeze their salaries since 2009, when the district, in the face of dwindling state funding and a nationwide recession, stopped giving annual raises.

This past spring, in collective bargaining negotiations that resembled a tug-of-war fought in the mud, CPS rejected union proposals outright. The teachers’ union, the Columbia Missouri National Education Association, accused the district of being manipulated by its lawyer and disloyal to employees; the district, just now exiting a grinding recession, decided its funds needed to be allocated elsewhere.

The debate has been fueled by a statewide scramble to fund schools, growing deficit spending by CPS with shrinking reserve funds, hundreds of new students, a handful of new schools, a schism in union representation and, with another school year ready to start, swelling frustration from everyone involved.

Adams has been a CPS teacher for 22 years, and she characterizes the past seven as some of the most difficult.

“I wouldn’t say that working conditions are bad,” she says, “but salaries are always going to be a struggle. Teachers aren’t valued and paid the same way other professions are.”

The trickle that turned to a drip

To understand the extent of the district’s funding crisis, you first need to look to a state-level crisis 15 years ago.

To understand the extent of the district’s funding crisis, you first need to look to a state-level crisis 15 years ago.

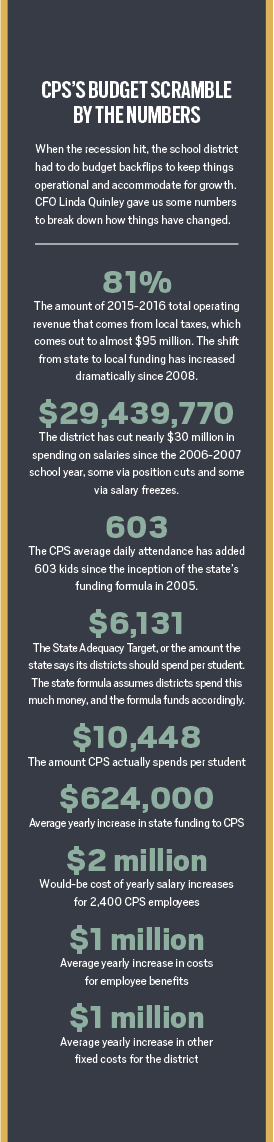

School districts draw money from three funding sources: federal, state and local taxes. From the late ’70s to 2000, the biggest burden fell on state government; according to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average state paid for about 49.5 percent of public education in 1999-2000, with the federal government funding 7.3 percent and the local communities funding the remaining 43 percent.

To determine how may dollars those percentages translate to, Missouri uses a formula: a district’s variables are put in, and a dollar amount comes out.

The ’90s were good to the Missouri economy, which meant the state government had no problem collecting revenue while keeping taxes low for Missouri businesses and citizens, as long as the state stayed economically active and successful. Otto Fajen, now the legislative director and a lobbyist for the Missouri National Education Association, worked in the Capitol at the time.

“There was a binge on tax cutting and tax credits and all that stuff,” Fajen says. “And they ultimately overdid it. And then there was an economic downturn, and the formula got dangerously out of whack.”

That meant school districts no longer got the amount of funding the state formula said they should get. After some legal trouble and advice from an outside consultant, the state devised a more efficient formula that could get state funding back on track. That formula was put in place in 2005; then the recession happened, and the formula was off track once again.

Thus, the funding was passed to local communities, such as Columbia, that found they had no one else to pass it to.

“2015 was the first sizable infusion we’ve had into the formula, and it was about $100 million,” says Ron Lankford, deputy commissioner for the State Department of Education. Lankford’s primary duty is school finances; he came to his job in 2010, right in the heart of the crisis. “And even with that, we’re still $442 million short.” When asked if that meant local taxpayers had to make up the difference, Lankford says, “That’s the only option they have.”

Fajen estimates the school funding in Missouri leans more local than almost any other state. The state averages a split of 9 percent federal, 34 percent state and 56 percent local; Columbia leans even further, at 8 percent, 24 percent and 64 percent. The evaporated state dollars in the CPS budget had to be replaced from somewhere, and in 2009, the district froze salaries.

The deep freeze

“I think that the first time it was frozen,” Adams says, “I was like, ‘OK, I’m taking this for the team.’ I felt very strongly that I was willing to be frozen so that other teachers, younger teachers, didn’t have to be cut.”

At first, this view prevailed for many of her fellow teachers: Times are tough but temporary.

“But the second time,” Adams says. “Well, it’s kind of depressing to know that you’re getting frozen and not know when you’re going to come out.”

CPS teacher salaries are raised on a step program; the longer you teach, the more steps you attain, and the more steps, the higher the salary. The steps — about $800 each — add up over a 20-year career, especially with regular increases in base salaries. They also add up in the district’s budget, which is why they froze.

The district cut back other areas before going after salaries. In April of 2008, they asked the public to vote for an increase in the district’s tax levy, and for the first time in the city’s history, the public said no. The district then slashed spending and cut dozens of positions; they consulted with their teachers and investigated every district program.

“A short day for me was 15 hours, and that was seven days a week,” says Linda Quinley, the district’s CFO. “We tried to stay as far away from the classroom as we could for as long as we could.”

But eventually, the district froze salaries. Not coincidentally, the blow to morale precipitated a growing schism among teachers. In 2007, a Missouri Supreme Court decision gave public school teachers the right to collectively bargain with their school boards. The same year, the Columbia chapter of the National Education Association asked for a seat at the bargaining table as the sole representative of Columbia’s teachers. Another teacher’s group, the Columbia Missouri State Teachers Association, resisted.

As their priorities shifted to unfreezing their salaries, the groups argued over strategy. The CMSTA, of which Adams is the current president, favors the district’s traditional meet-and-confer style of negotiating. The system’s meetings are informal: essentially brainstorming sessions about where the district’s money should go. The CMNEA, conversely, pushed for formalized collective bargaining. They wanted one united front of teachers to negotiate formally, fearlessly and unapologetically.

“I’ve never seen it as very democratic when you have people representing an entire group,” Adams says. “About one-third of our teachers don’t belong to either group, so they just get sort of fluffed out of everything. With meet-and-confer, at least you make sure that the other two-thirds are getting their voices heard.”

The unrepresented third, however, disagreed. In 2012, the teachers voted the NEA in as their sole representative and only bargaining union.

The rise of the NEA

In the 15 years before winning the vote, CMNEA membership had grown more than 20-fold. When current President Kathy Steinhoff attended her first NEA meeting in 2000, membership had gone from 30 to 200 in the three previous years; it now hovers around 650.

In the 15 years before winning the vote, CMNEA membership had grown more than 20-fold. When current President Kathy Steinhoff attended her first NEA meeting in 2000, membership had gone from 30 to 200 in the three previous years; it now hovers around 650.

“I went to one meeting, and I thought it was fabulous,” Steinhoff says. “I go to this meeting, and it’s not just about my classroom but about protecting teachers and protecting the profession and looking out for kids on a higher level. I felt kind of naïve to think that I’d never thought about it before, but I knew I wanted to be part of it.”

In July, Steinhoff succeeded former President Susan McClintic, who retired from teaching after tripling NEA membership during her term. McClintic plans to run for the 47th district seat in the Missouri House of Representatives.

When asked about the challenges of teaching in Columbia, the two women don’t immediately go to salaries, instead starting with poverty in Boone County, which they say has forced the district to address new needs. When asked where the money to meet these needs was coming from, Steinhoff quietly laughs.

“I think that’s where you see the teachers’ union advocating for higher salaries,” she says. “And I think that if you were to look at a large majority of school districts across the nation, it would be unusual to see teachers’ salaries remain stagnant, not to mention a step frozen, over the last 10 years.”

“We don’t see that in Jefferson City or Springfield,” McClintic says.

Regional comparisons are a cornerstone of the CMNEA argument. A little later, Steinhoff pulls out a thick research document prepared by the state NEA. The last page ranks teacher salaries for the 20 largest districts. Columbia ranks 19th, and Steinhoff expects to be 20th next year.

In their first years as the official union, the CMNEA made progress. In 2014, they negotiated a three-year contract that included, at last, the restoration of one of the frozen salary steps.

Then, last spring, their progress abruptly ended.

Difference in opinion

Months after negotiations ended with zero changes to teachers’ contracts, the two sides are still far apart on why talks derailed. The union had asked for another restored step, in addition to other nonsalary demands about planning time and schedules. They received nothing.

“I think that the frozen step would have been fiscally sound,” McClintic says. “I think it would have earned them great faith from their employees, and it would have been done away with, and now it’s hanging over our heads for another year.”

“I’m not sure there’s much that we could have done differently,” Steinhoff adds.

The NEA felt that a $1.8 million infusion from the state should go to the teachers. Adams felt the NEA was too confrontational, which she found “a little frustrating and embarrassing.” School board members felt confused.

“I’m not sure if the NEA didn’t believe our funding projections or what,” says Darin Pries, board member and former chair of their finance committee. “But restoring the step didn’t seem like the best choice.”

All parties agree the school board has been, at a big-picture level, fiscally remarkable. Despite the swing in funding balances, they’ve added students and built schools, convinced the public to pay increased taxes and carefully spent down budget reserves they accumulated before the crisis.

“The storm has lasted a little bit longer than we expected,” Quinley says. “And now we have tough years ahead. We want to continue to be a district that’s good with the public’s money.”

The NEA argues that a recovering economy should make up for past sacrifices. But once again, the water flows from the top of the stream — in this case, Jefferson City.

Senate Bill 509, a tax cut that bulldozed the governor’s veto last year, will decrease state tax revenues over the next five years, as will another bill currently passing through the Missouri Legislature. Even with a fully funded formula, the state is still using numbers from 2008 to fund CPS. Quinley says this translates to about a $5,000 shortage per student.

A tax cut at the state level, of course, causes tax increase at the local level, and Quinley says the district might ask for another levy increase, the first since 2012, this year. Columbia’s school tax rate is already 486th highest of the state’s 520 districts.

“We have had a public that’s been willing to pick up the ball and run with it,” Pries says. “But that’s not always guaranteed.”

As the district prepares for another hit, teachers are still hoping they’ll be unfrozen. But the conversation is ongoing and bitter.

“Negotiations are the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my professional life; I can tell you that,” Quinley says. “We know that we can’t stay stuck in 2007 forever, and the school board is going to be very busy this fall.”

“These conversations need to be about students first and adults last,” she adds

Adams, in some ways, agrees. “Our No. 1 priority is giving the best education to kids,” she says. “But our second priority is that we want to get compensated for that as well. I’m not sure there’s a plan to come together and fight for that, but there it is.”